Business & Economics

Freedom from extreme poverty as a human right

Former Deputy Prime Minister Brian Howe revisits Professor Ronald Henderson’s seminal work on poverty, and explains why the case for a basic income is relevant today now more than ever

Published 13 February 2018

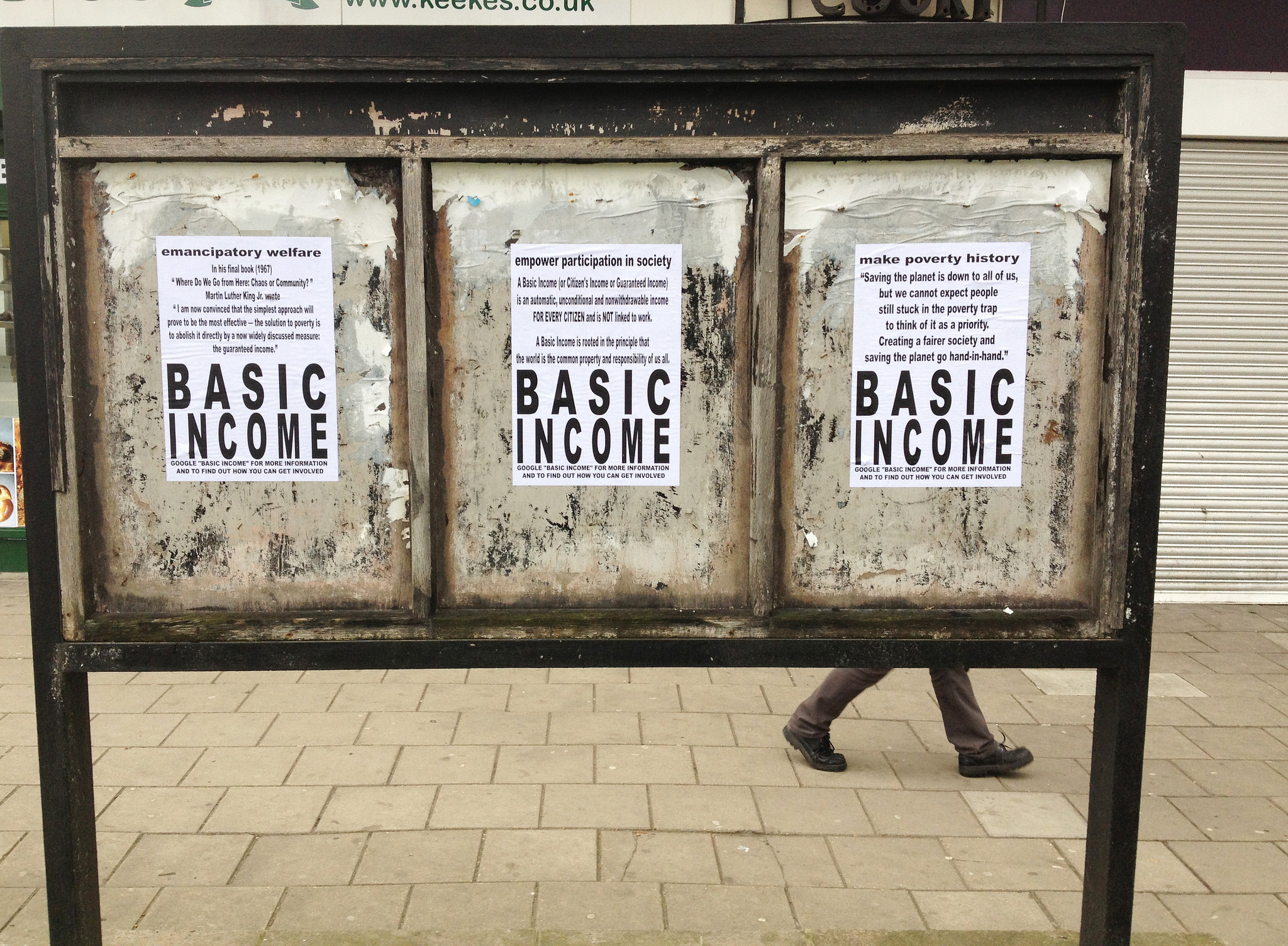

Around the globe, the concept of a universal basic income (UBI) is controversial.

This notion - that the government should pay everyone a regular payment to meet their basic needs, despite their income - has been touted as a solution to growing inequalities and the polarisation of labour markets.

Here in Australia, the idea of a UBI has floated in and out of our political arena for years, but remains only that, an idea.

But in the 1970s, it looked as though it could become more.

In 1972, the inaugural Director of the Melbourne Institute, Applied Economic and Social Research, Professor Ronald Henderson, chaired the Australian government’s poverty enquiry. It was tasked by then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, to investigate all aspects of poverty affecting Australians, including race, education, health and law.

Professor Henderson’s work led to what is now widely referred to as the Henderson Poverty Line, which measures the extent of poverty in Australia in terms of the income of families and individuals relative to their essential living costs; and he advocated a guaranteed minimum income scheme for Australia, similar to a UBI.

More than 40 years after Professor Henderson’s began his report of the Commonwealth Commission of Inquiry into Poverty with the line “poverty is not just a personal attribute: it arises out of the organisation of society” - is his call for welfare reform still relevant today?

Professor Henderson led the inquiry from 1972 to 1975. It was - and remains – Australia’s most extensive attempt to study poverty, understand its context and impacts, and recommend lasting policy changes.

At the heart of the inquiry’s final recommendations was a guaranteed minimum income scheme, in which payments to pensioners (at a high rate) and payments to all other income units (at a lower rate) would be balanced by a proportional tax on all private income.

The report states: “We believe that these reforms are the best way of reconciling the conflicting ends of policy on income support. They provide minimum incomes so that Australians will not in future fall so easily into poverty, and yet preserve the incentive to earn a private income, in that all who do so are better off.

“They recognise that disabilities which hinder the earning of a private income warrant favoured treatment, but also provide support for people without disabilities in this sense, and who may still easily become poor – particularly the large family. Again, support is provided in a way which does not discredit those who claim it, and so take up rates should be high.

“Further, the proposals should be administratively workable, and limit the area of administrative discretion, so that income support may be seen as a right rather than a favour.”

Professor Henderson was strongly in favor of universality in social policy - as exists in Medicare today in Australia. And that’s tangible in his idea of a universal minimum payment which would have ensured that incomes for individuals and families were in excess of the poverty line.

Instead of means testing - which he opposed as they create a separate system for the disadvantaged that can be stigmatizing - he wanted to use the tax system to withdraw income from higher earners, rather than means testing pensions and benefits.

Business & Economics

Freedom from extreme poverty as a human right

But this didn’t happen.

Instead, the Whitlam government was dismissed in 1975 – around 6 months after the inquiry delivered its final report, and the new government, headed up by Malcolm Fraser, hardly considered its recommendations.

At the time of Professor Henderson’s pivotal work, post-war Australia had pursued the creation of an industrial economy where male workers played the dominant role. For the most part, employment then meant permanent full-time jobs in industry regulated and protected against foreign competition.

But, since that time, the country has pursued a very different course. Our modern labour markets have been shaped by an ageing population, changing family characteristics, increased casual and part-time workers, and improved gender equity.

In his time, Professor Henderson found that to be in work was to be out of poverty. But today, employment looks markedly different - with an increasing number of workers now employed in part-time or temporary jobs.

The diverse and fragmented nature of today’s workforce has made the protection of working conditions more difficult, and union membership has rapidly declined. The increasing power of employers to dictate terms of employment is reflected in the declining wages share in an economy marked by increasing inequality.

This month, the Melbourne Institute and the Brotherhood of St Laurence will host the inaugural Henderson Conference. More than 20 expert speakers will review how Australia’s social security system can better respond to poverty and inequality.

Business & Economics

Where did all the money go?

The key challenge for the experts is how Australia can maintain its commitment to fair and equitable wealth generation and distribution, in a modern world.

The precarious nature of modern labour markets puts enormous pressures on families and households, making it important to create a system that works in the interests of the truly disadvantaged.

Professor Henderson distrusted a targeted social security system, and therefore recommended a basic income so that “income support may be seen as a right rather than a favour” for Australian citizens.

Since then, despite the example of universality in the key public institution of Medicare, to which all are entitled, the social security system has become more conditional, and arbitrary, with benefits now well below the poverty line.

There is growing evidence, for example, that social security payments for unemployed people, like Newstart, now barely meet the necessities of life – let alone cover expenses involved when people are looking for work.

In this country, we increasingly celebrate entrepreneurial self-reliance, but for disadvantaged people, the certainty of an adequate income is a fundamental foundation.

It may not be sufficient, but it is necessary.

As Professor Henderson said during a speech at a Remembrance Day rally in 1984 “we all have a right to a decent minimum income: to a fair share”.

The 2018 Henderson Conference will be hosted at the University of Melbourne from February 15-16. To register follow the link here.

This article has been copublished with The Conversation.

Banner image: Russell Shaw Higgins/Flickr