Hiding in plain sight

An ocean once thought of as free of pollution is a source of a particularly toxic form of mercury called methylmercury

Published 2 August 2016

You would think there is nowhere to hide in the forever-winter wonderland of Antarctica. But scientists have shown where something can hide in plain sight for years – in the atmosphere and sea ice.

University of Melbourne geomicrobiologist Dr John Moreau and PhD student Caitlin Gionfriddo have discovered significant quantities of methylmercury – an especially toxic form of mercury – in sea ice in the Southern Ocean.

The study, published in the journal Nature Microbiology, was done in collaboration with the Centre for Systems Genomics at the University of Melbourne, the US Geological Survey, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

It reveals the sea ice harbours bacteria that are a source of methylmercury, which can be released into the ocean and possibly contaminate the ecosystem’s food chain.

Ms Gionfriddo says the motivations behind the study were to examine the connection between mercury and the food we eat, and to understand global cycling of mercury in the atmosphere and oceans.

“There are high levels of methylmercury in our ecosystems, especially in the marine environment, but we don’t know how it’s being produced,” she says. “We’re seeing it accumulate in the food web and most of it likely comes from atmospheric deposition of mercury onto sea water.”

This atmospheric dumping occurs all year long but increases during the Antarctic spring, when longer daylight hours boost the amount of mercury that falls onto sea ice and the ocean.

Mercury is a heavy metal pollutant that can be released into the environment through natural sources, such as volcanic eruptions and re-released from vegetation during bushfires. It is also created through human activity, such as gold smelting, burning fossil fuels, plus it is also a legacy from some mining sites.

The most common way for humans to be exposed to mercury is through food consumption, such as fish. Mercury also builds up in the food chain through a process called bioaccumulation – so if you eat a piece of fish that itself ate two other fish that contained mercury, you will be consuming mercury levels from all three animals.

Produced by bacteria

Humans are at the top of the food chain and so are at risk of accumulating harmful amounts of mercury from consumption of seafood.

Methylmercury is produced by bacteria that live in oceans, lakes, rivers and other water bodies, and comes about when hydrogen and carbon is added to mercury that has deposited from the atmosphere onto sea ice.

It is a more toxic form of mercury that can easily travel from the stomach to the bloodstream, reaching the brain. If ingested, it can cause developmental problems in foetuses, infants and children. In the most serious cases, it can lead to physical malformations.

Just why bacteria does this is not known, despite scientists trying to find the answer for the past 50 years.

“It’s a good question,” Dr Moreau says. “After half a century of research, we still don’t know why. Most people think it’s just an accidental side reaction, some people think it’s a response to toxicity.”

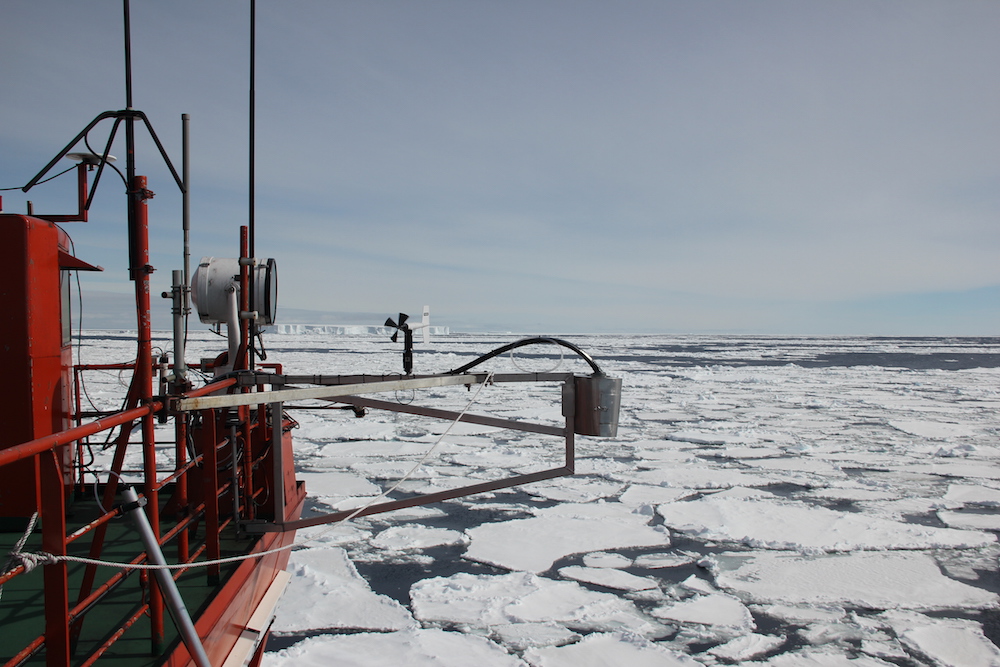

In order to collect samples for the study, Ms Gionfriddo spent two months aboard an icebreaker in the Antarctic, along with scientists from other disciplines including marine biologists and atmospheric chemists.

“It was amazing, it was like living in a snow globe for two months,” Ms Gionfriddo says. “The boat crew put a plank down from the boat onto the ice and it’s several metres thick. You don’t realise that you’re on the ocean at that point, because it just looks like land. It’s insane.”

Mercury has an atmospheric life of about a year and during that time can travel across the world, Ms Gionfriddo says. That means mercury released through burning fossil fuels in China, for example, could go up in the atmosphere and end up in a toxic form in the seawater of Antarctica

Being geographically isolated is seemingly no protection from toxins, both human-made and natural.

“Some people think that because the Southern Ocean’s so far removed from industrial contamination in the northern hemisphere that it’s less of a problem,” Dr Moreau says.

There is limited commercial fishing in the Southern Ocean but thanks to depleting stocks in other oceans due to over-fishing, more companies are looking south. The Antarctic toothfish, Patagonian toothfish, Mackerel icefish and Antarctic krill are popular with consumers.

There is also a substantial illegal industry, which sells fish as sourced from other locations. That means that the mackerel on your plate labelled as being from the Atlantic Ocean could be from the Southern Ocean.

The next step in Dr Moreau’s and Ms Gionfriddo research is to examine what environmental and microbial factors are behind the creation of the methylmercury found in sea ice and to what extent it contaminates the marine life that lives in Antarctic waters.

“I don’t think we know what the effects are yet and that’s part of the motivation for the study,” Dr Moreau says.

Banner image: An iceberg in sea ice/Caitlin Gionfriddo