Hiring for personality, training for skill

As workplaces demand more of their employees, having only technical skills or expertise is no longer enough. Instead, the emphasis is on multi-skilled individuals making up a team

Published 9 October 2017

Hiring for personality, training for skill

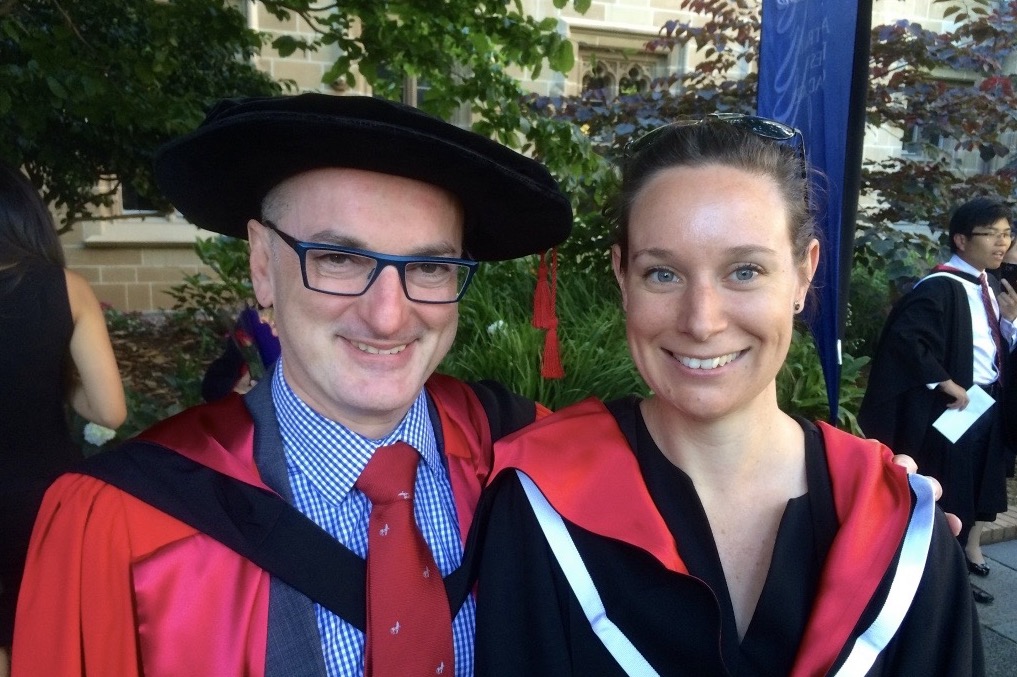

Amy Halliday is the face of a new generation in medicine. At the age of 34, she has just been accepted into the neurology advanced training program at St Vincent’s Hospital, an achievement made more notable by the road she travelled to get there.

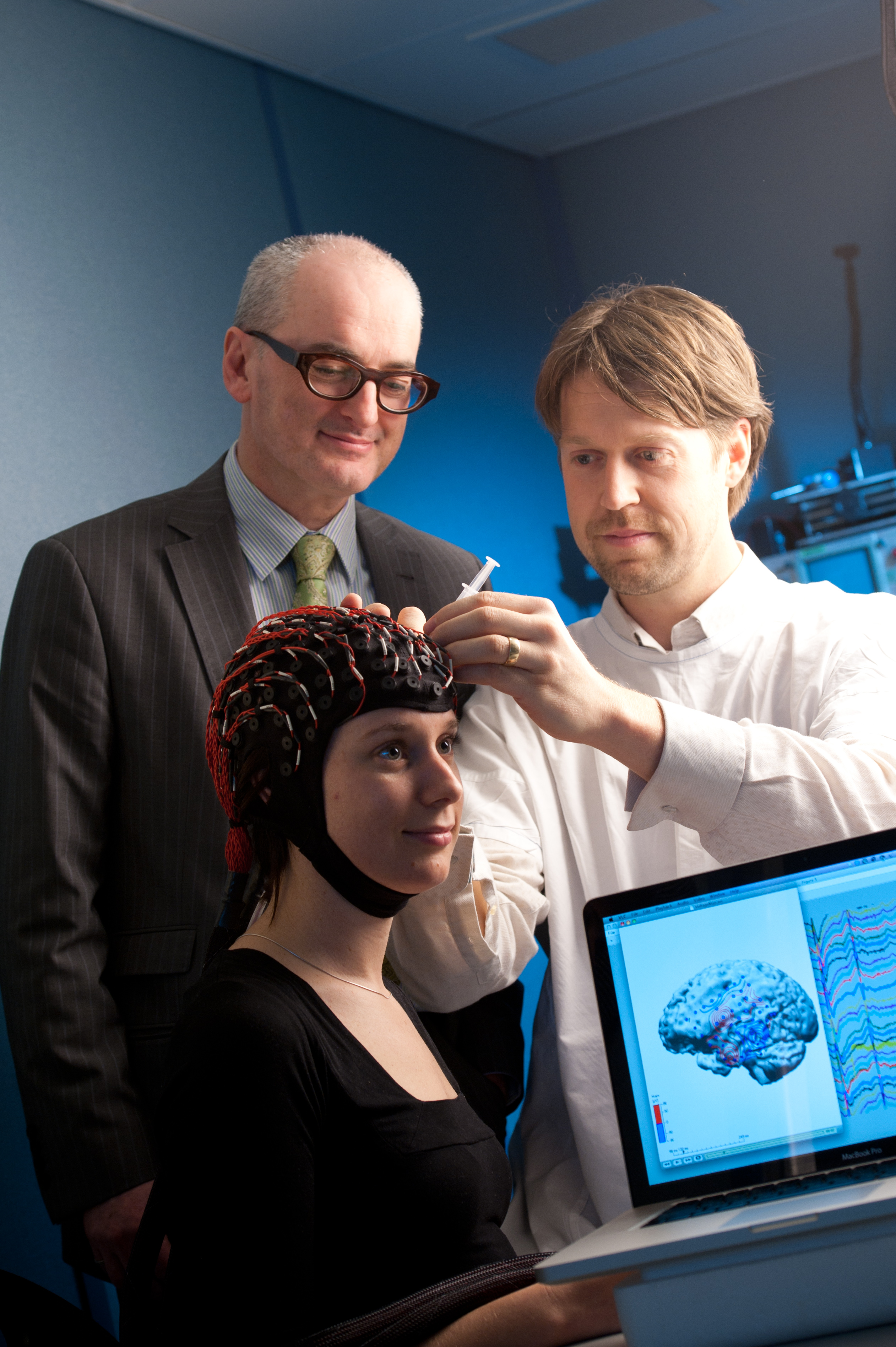

The first in her family to complete high school, Dr Halliday graduated from university with an honours degree in neuroscience. She was hired as a research assistant by University of Melbourne Professor Mark Cook, the Director of Neurology at St Vincent’s Hospital, who also heads up the Graeme Clark Institute for Biomedical Engineering.

The Graeme Clark Institute is on the bold frontier of medicine. Teams of biomedical engineers and clinical researchers work collaboratively with industry partners to develop new bionic devices, implants, drug treatments and assistive technologies like prosthetics, as well as diagnostic tools for medical professionals.

Dr Halliday was on the team that developed a new device, a sort of ‘FitBit for the brain’ that has the potential to predict and prevent epileptic seizures.

The possibilities of the work ignited her passion for neurology. Within three years of graduating from the University of Western Australia, she had decided to study medicine through the graduate entry pathway at the University of Melbourne.

Taking the indirect approach

Dr Halliday’s circuitous path to medicine is in sharp contrast to the direct route taken by her mentor, Professor Cook, now also Sir John Eccles Chair of Medicine at the University of Melbourne, in the 1970s.

“It was a completely closed world in medicine then,” he explains. “When you were 17 or 18, you got on the tram at the first stop and you stayed on until the terminus.”

That singular approach might no longer be sustainable in today’s world where an ever-changing workplace demands multi-skilled graduates.

Isabel Metz, a Professor of Organisational Behaviour at the Melbourne Business School, agrees.

“Diversity is hailed as being good for organisations because it leads to creativity and innovation. People with different experiences and different learning will have different ways of solving problems.”

Developing only technical skills or expertise is no longer enough in today’s workplace, she adds.

“Graduates also need to have skills that we call by the misnomer ‘soft skills’. They enable you to liaise better with people, to elicit information from people who are experts in areas that you don’t have knowledge of, and to use that information in a way that will help you to do your job.”

And Professor Cook agrees. Communication is critical, he believes, because the power of cross-disciplinary teams holds the key to future breakthroughs in medicine.

“The opportunities that give rise to new therapies come through the interaction in areas where there is not, at first sight, an obvious connection.

“While there is a focus on having multi-disciplinary teams, what’s more important I think is having teams that understand the content of their colleagues’ work and the language they use to express that.

“This is convergent stuff rather than multidisciplinary stuff where you have teams assembled that are multi-skilled, rather than teams comprising a range of skills. That’s an important difference.”

Cross-discipline opportunities

The intent of the Melbourne Model used at the University of Melbourne, where medical students already have a degree in another specialty, is to better prepare them for the workplace.

“It generates opportunities where you can move across disciplines and take with you the knowledge, the language and background of a different way of solving problems,” says Professor Cook.

That philosophy has guided many of his choices in staff.

When he hired Dr Halliday as a research assistant, he also hired another graduate whose PhD investigated the dynamics of rowing a boat in competition.

“He was interested in solving a complex problem that had a lot of contributory components, none of which were easily controlled; and I was interested in people who had a good approach to a unique problem and brought with them no preconceptions, and had previously solved a complex problem using a novel strategy.”

Dr Halliday’s background in science and research helped smooth her transition into her medical career.

“I think it also helps to have a bit more experience under your belt,” she says. “You can approach patients with a bit more maturity and you get a better grasp of the big picture with more life experience behind you.

“I also think that having worked as part of a team has been really helpful. You learn to communicate your knowledge and put it into a framework that someone not in your group will understand.

“You learn a respect for each other’s discipline. I often think about Professor Cook’s mantra: ‘Hire for personality and train for skill’.”

Banner image and video: Getty Images