Politics & Society

Nowhere people have a right to somewhere

The Indian National Register of Citizens aims to separate 4 million “illegal” immigrants from “legitimate” residents. So, what does history tell us about the impact of removing citizenship?

Published 8 August 2018

Last week’s controversial decision by the Indian government to formulate a National Register of Citizens (NRC) risks denationalising four million citizens. The draft of the document in Assam included 28 million people as citizens, but excluded some four million residents in the state which sits in India’s northeast.

This is the most recent example of practices that threaten the citizenship rights of an ethnic minority, highlighting that the prevention and eradication of statelessness is an ongoing challenge in the modern world.

The NRC forms part of a longer process initiated in 2005 to revise Assam’s citizenship records. It is a list of ‘bone fide’ Indian citizens, which Assam law defines as people who are able to prove that they were in India before March 24, 1971 – the year that neighbouring Bangladesh declared independence.

Thousands of people fled to India from Bangladesh in the early 1970s, prompting widespread anti-immigrant agitation. The ethnic clash culminated in the bloody massacre of 1983 that claimed the lives of at least 1,800 Muslim migrants.

Politics & Society

Nowhere people have a right to somewhere

Thirty three years ago, in an attempt to calm the agitation, the Assam Accord of 1985 was agreed which aimed to “protect the social and cultural identity of the Assamese people”. Also agreed was that cut-off date, March 24, 1971, which meant that all illegal foreigners who came to Assam on or after that date would be detected and deported from the state.

The final draft of the NRC is due to be published in December this year. While government officials have assured those who have been excluded from the list that they will be given the chance to file an appeal and that “no one will be sent to detention camps,” many human rights’ activists have stressed that the NRC disproportionately targets Muslim minorities, leading to further discrimination, persecution and statelessness.

The UNHCR estimates there are at least 10 million stateless persons globally, with 75 per cent of the world’s known stateless populations belonging to an ethnic minority.

Statelessness is an insidious cycle: it often impacts the most vulnerable populations, leaving those populations vulnerable to severe human rights violations. As the Supreme Court of the United States wrote in dissent in 1958: “citizenship is man’s basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.

“Remove this priceless possession and there remains a stateless person…He has no lawful claim to protection from any nation, and no nation may assert rights on his behalf.”

But despite its often-devastating impact, statelessness as a human rights issue remains underexamined.

History tells us that discriminatory nationality laws and policies have often marked the first phase of systemic, institutionalised persecution and ongoing human rights violations.

The United Nations recently described the ongoing plight of the Rohingya Muslim population in Myanmar as a “textbook case of ethnic cleansing” – giving us an insight into the dangers of statelessness. The roots of this escalating humanitarian crisis can be traced back to the removal of citizenship.

Politics & Society

Pariah to partner: The West’s premature embrace of Myanmar

In 1982, Burma passed a law that excluded the Rohingya from its list of ethnic populations entitled to citizenship, effectively revoking the citizenship of most of the Rohingya population. The removal of citizenship rights and protections from its Muslim minority population left the Rohingya stateless, and immediately vulnerable to widespread violence, oppression and displacement.

Going further back in history, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Jews and other minority populations were often excluded from citizenship in countries across Europe.

The most horrific example is during the Second World War. Legislation enacted in July 1933 stripped German Jews and other minority groups of their citizenship, rendering them effectively stateless, and this deprivation of nationality formed part of Nazi Germany’s 1935 Nuremberg laws, designed to ostracise and dehumanise the Jewish population.

The writer, George Eliot, famously penned “history, we know, is apt to repeat herself, and to foist very old incidents upon us with only a slight change of costume”.

While history may not exactly repeat itself, its patterns can be frighteningly obvious.

With Assam’s recent exclusion of its Muslim minority population from its citizenship rolls, it’s difficult not to fear an historic recurrence.

At the very least, the recent development in Assam is a wake-up call to take seriously the need for greater understanding of the links between discrimination and statelessness, and the need for countries like Australia to take leadership on the issue; in order to address the danger of history repeating.

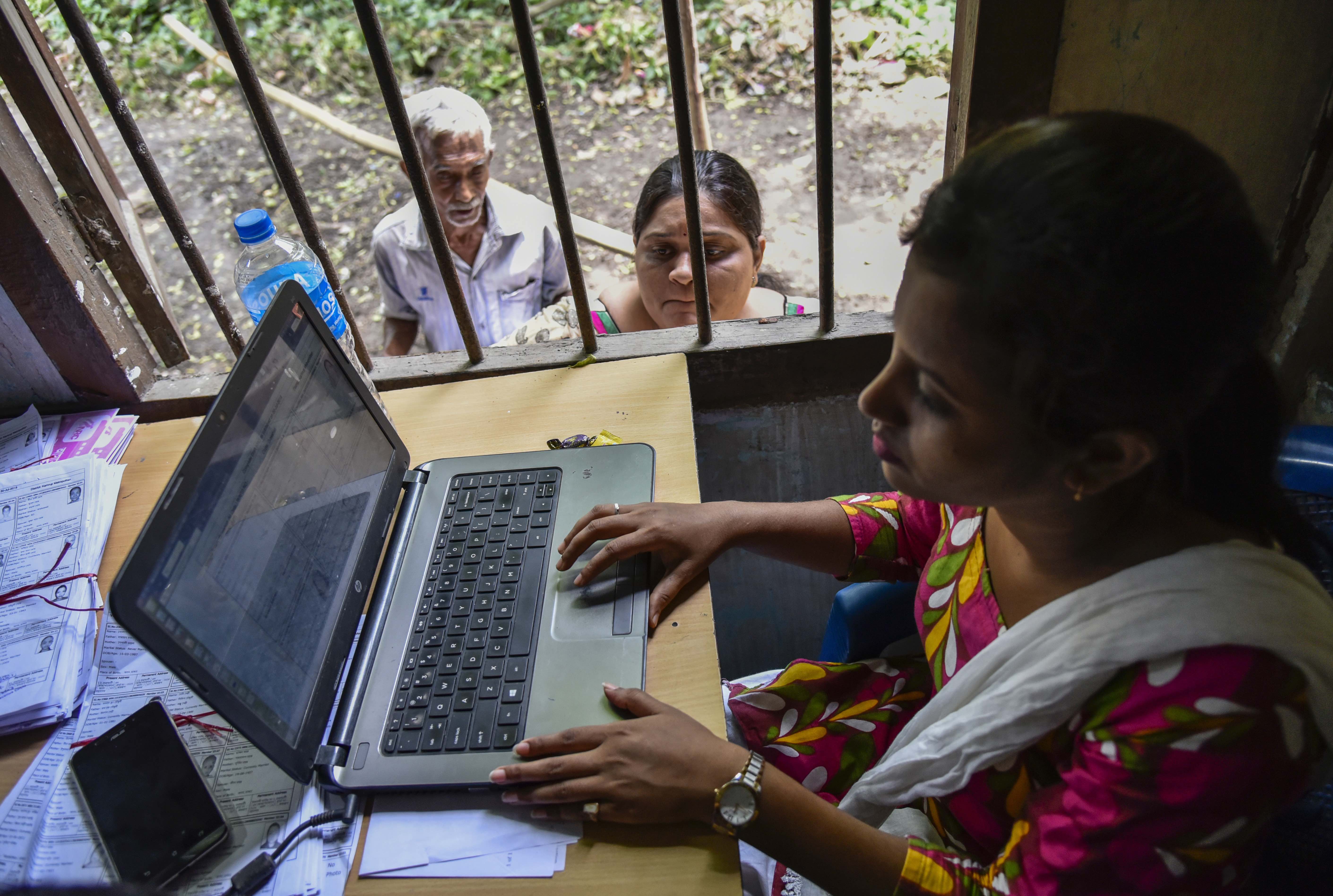

Banner: Residents hold their documents in a queue to check their names on the final list of National Register of Citizens/Getty Images