Health & Medicine

Black Saturday: the hidden costs

High levels of psychological stress among taxi drivers have led to a world-first mental health app tailored to the demands of the job

Published 7 February 2017

Stressed at work? Tired of sitting down? You could go for a run or a long walk, or maybe just lie in a park. But it’s not so easy if you are a taxi driver and any time out means missing the chance of a fare. Taxi drivers can spend as much as eight hours simply waiting around during any 12 hour shift, but it’s difficult to relax when the clock is ticking and you can’t ever be far from the car and a potential fare.

It is a recipe for stress and anxiety that is fuelling levels of psychological distress among drivers at rates that new research suggests are five times worse than the rest of the population.

But University of Melbourne researchers are now aiming to do something about it, developing a mental health mobile phone app that is specifically designed to fit around the needs and working lives of taxi drivers.

“Taxi drivers are a highly vulnerable population, reporting high rates of psychological distress,” says researcher Dr Sandra Davidson, a Senior Research Fellow at the Department of General Practice within the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences.

“The majority of urban drivers are from non-English speaking backgrounds and our research shows that they are working long hours, 60-70 hours a week in 12 hour shifts, that involve incredibly long periods of sitting down. But they are also a population that is hard to reach with health interventions because of their unique working environment.”

The app, which is still a prototype, offers physical and mental exercises tailored to whatever time a driver can spare, whether inside the car or out. It offers options for a two-minute session, a five-minute session or a 10-minute session. It includes exercises similar to those recommended for long-haul flights, as well as muscle relaxation to combat anxiety. There are also mindfulness sessions such as listening to guided-imagery as a relaxation tool.

“The ultimate goal is improving the mental health of drivers, but we are focusing also on their physical health as a way to do that,” Dr Davidson says. “Muscle tension can build up in drivers over long periods of time and that can lead into feelings of stress. We know that sitting down for long periods isn’t good for you so a lot of our exercises are about breaking up those long periods of sitting down.”

The app also reminds drivers to stay hydrated and will link to useful information such as the location of public toilets. Some previous research has shown that taxi drivers are at higher risk of kidney and urinary tract infections because of the excessive time they spend seated and delaying going to the toilet.

It will also include health tips from other drivers. One driver told the researchers that he lost eight kilograms just by getting out of the cab to open the door for his passengers and getting out to knock on the doors of booked addresses rather than simply tooting his horn.

Dr Davidson is a mental health expert and had identified taxi drivers as a hard to reach and vulnerable group because they are a male-dominated profession that includes many drivers from non-English speaking backgrounds. But when she investigated she was shocked to find there was virtually no research on the mental health of taxi drivers here or anywhere else around the world. She was further shocked to discover how bad their mental health appeared to be.

When she carried out a mental health survey of over 200 drivers waiting for fares at Melbourne Airport’s taxi holding yard, she found that almost two-thirds of respondents reported “high psychological distress”.

Health & Medicine

Black Saturday: the hidden costs

High psychological distress is indicative of a potential serious mental health problem, and was reported at a rate that was five times the average for Australian men. Of these almost a quarter reported that they hadn’t seen a health professional of any kind in the last 12 months. But almost a third of drivers rated their health as only fair or poor, twice the rate for average Australian men.

“We know from other research that people who rate their health as only fair or poor, really do have poor health, and are at risk of future long term negative health outcomes,” Dr Davidson says.

She says taxi drivers face a trio of high-risk factors, including generally having low incomes, doing shift work and often being recent migrants. The majority of respondents to the survey were migrants, of which half had settled in Australia in only the last ten years. But she was nevertheless surprised at the high rates of self-reported stress. “The rates of psychological distress they are reporting are huge.”

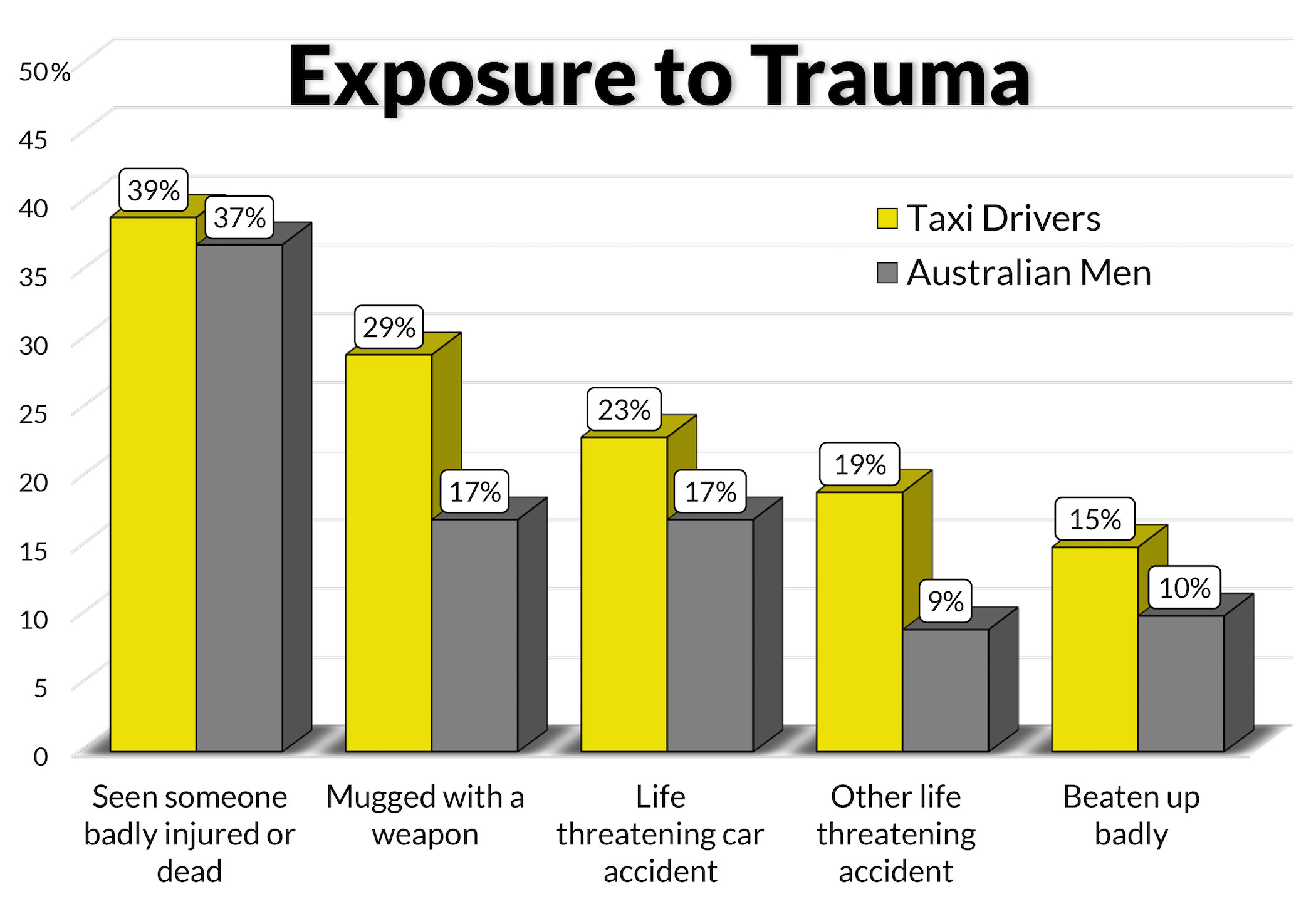

The survey work also revealed that taxi drivers are more likely to have been beaten up, mugged with a weapon, and have experienced a life threatening accident when compared with average Australian men, though these experiences may not necessarily have happened on the job. Dr Davidson says driving the night shift corresponded with drivers being more likely to report high levels of psychological distress.

The challenge then for the researchers was to come up with an intervention that could fit around the unusual working lives of the drivers, while also appealing to them and being easily accessible to a group where language is a barrier.

The idea for a mental health mobile phone app came out of Dr Davidson’s research on the habits of drivers, based on surveys and interviews. She found that almost all the drivers used smart phones to help pass the time, mainly using them for staying in touch with friends and family, searching the web and social media. But they rarely used technology when they were at home.

She also found that they were more comfortable talking about physical health issues rather than their mental health. It was clear that such a group was unlikely to use traditional online mental health sites.

“We needed an intervention that could work within the unpredictable breaks they have between jobs, and that could be accessible through their smart phone. We knew they weren’t going to take time out to go to a quiet library and spend a lot of time on a mental health site or spend that time when they are at home when they’d rather be playing with their kids or catching up with friends.”

One initial idea was to explore whether the researchers could develop a video game app that would engage drivers and help their mental health at the same time. “There is some emerging research into using video games in this area given that we know that play can help mental health and the challenge here was to engage the drivers, and that is what games aim to do.”

But when she surveyed drivers on the use of their smart phones only 42 per cent said they played video games. Among drivers aged over 50, who made up 24 per cent of drivers in the survey, only 18 per cent said they played video games on their smart phones. These findings raised doubts over whether a game would generate enough take up.

Initial experiments also cast doubt on the effectiveness of casual video game playing in reducing stress. One of Dr Davidson’s research students, Raymond Su, recruited 60 people to play either a puzzle-type video game (Monument Valley and Prune), a narrative video game (80 Days and Minecraft: Story Mode) or undertake an online mindfulness exercise (Mindfulness.com) for a period of 40 minutes and compare their levels of anxiety before and after. The anxiety measures included blood pressure, pulse rate and a survey – the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. While all three showed some reduction in measured anxiety, the reduction was very small and was largest for the mindfulness exercise.

“Video games have potential for further research but probably not for this population,” she says.

Health & Medicine

Helping survivors overcome disaster trauma

The mental health app also provides an opportunity for the researchers to leverage the natural inclination of drivers to socialise together when out on the job. The researchers are working to added a section to the app where drivers can share health advice between themselves. Such a feature will need to be carefully curated since the researchers have a duty of care to ensure the app is giving out the right advice, but Dr Davidson is committed to making the feature work.

“Taxi drivers are an overwhelmingly social bunch – it is the wrong profession for an introvert. So what we want to do is tap into that social connectedness that taxi drivers have.”

The prototype of the app is scheduled to be ready for testing among drivers in March and Dr Davidson plans to follow up the testing with feedback surveys and focus group interviews to make sure that they come up with an application that not only improves the health of drivers, but is actually used by them.

“The whole process of this research has reinforced the fact that you don’t do research to prove yourself right, you do research to find out what is going on. That means building up your knowledge step by step and recognising that sometimes some ideas, like the video game idea, don’t deserve to go very far and you need to look elsewhere for something that can work.

“It is a painstaking approach and it can be slow but it is what research is all about.”

The Driving to Health project team includes Dr Sandra Davidson, Associate Professor Darryl Wade, Dr Greg Wadley, Associate Professor Nicola Reavley, Dr Susan Fletcher and Professor Jane Gunn.

The Melbourne Networked Society Institute at the University of Melbourne, and the Shepherd Foundation is supporting Dr Davidson’s research.

Banner Image: Paul Burston, University of Melbourne