Health & Medicine

Eating supplements cannot beat the real thing

Research finds a link between some of the most popular heartburn treatments and iron deficiency, which can lead to anaemia

Published 14 October 2018

If you studied chemistry at school, you would probably be aware of the dangers of touching hydrochloric acid. This hazardous, corrosive and smelly chemical comes with a lot of safety requirements including wearing gloves and masks when you’re handling it.

What you may not know is that this toxic substance plays an essential role in our own bodies.

Our stomachs produce hydrochloric acid for the digestion of meat and, importantly, the absorption of minerals like iron. But sometimes, this acid doesn’t stay only in our stomachs. Instead, it moves up and creates an uncomfortable, burning sensation around the breastbone – commonly called heartburn.

This feeling is a symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease, which affects more than 2 million Australians.

As a result, many of us turn to popular medications that suppress gastric acid secretion to manage the reflux disease and its symptoms. The most widely prescribed medications of these acid suppressants belong to a drug class called proton pump inhibitors or PPIs for short, which are used for conditions including indigestion, gastroesophageal reflux and gastric ulcer.

Health & Medicine

Eating supplements cannot beat the real thing

According to Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), over 19 million prescriptions of PPIs were written in Australia between 2013 and 2014.

A study conducted at a major teaching hospital in Tasmania showed that only 37 per cent of patients receiving PPIs were appropriately prescribed, which suggests these drugs are overprescribed. Other evidence also suggests that doctors seem too easy-going when it comes to increasing both PPI dosage and length of use.

But our research, the first population-based study of its kind, found these widely prescribed acid suppressants and their dosage and length of use were associated with iron deficiency.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), iron deficiency is the top nutritional disorder in the world and the direct cause of anaemia in half of cases.

While many of us have heard about anaemia, few are aware that this condition, if left untreated, can cause serious health problems and in exceptional cases even lead to death.

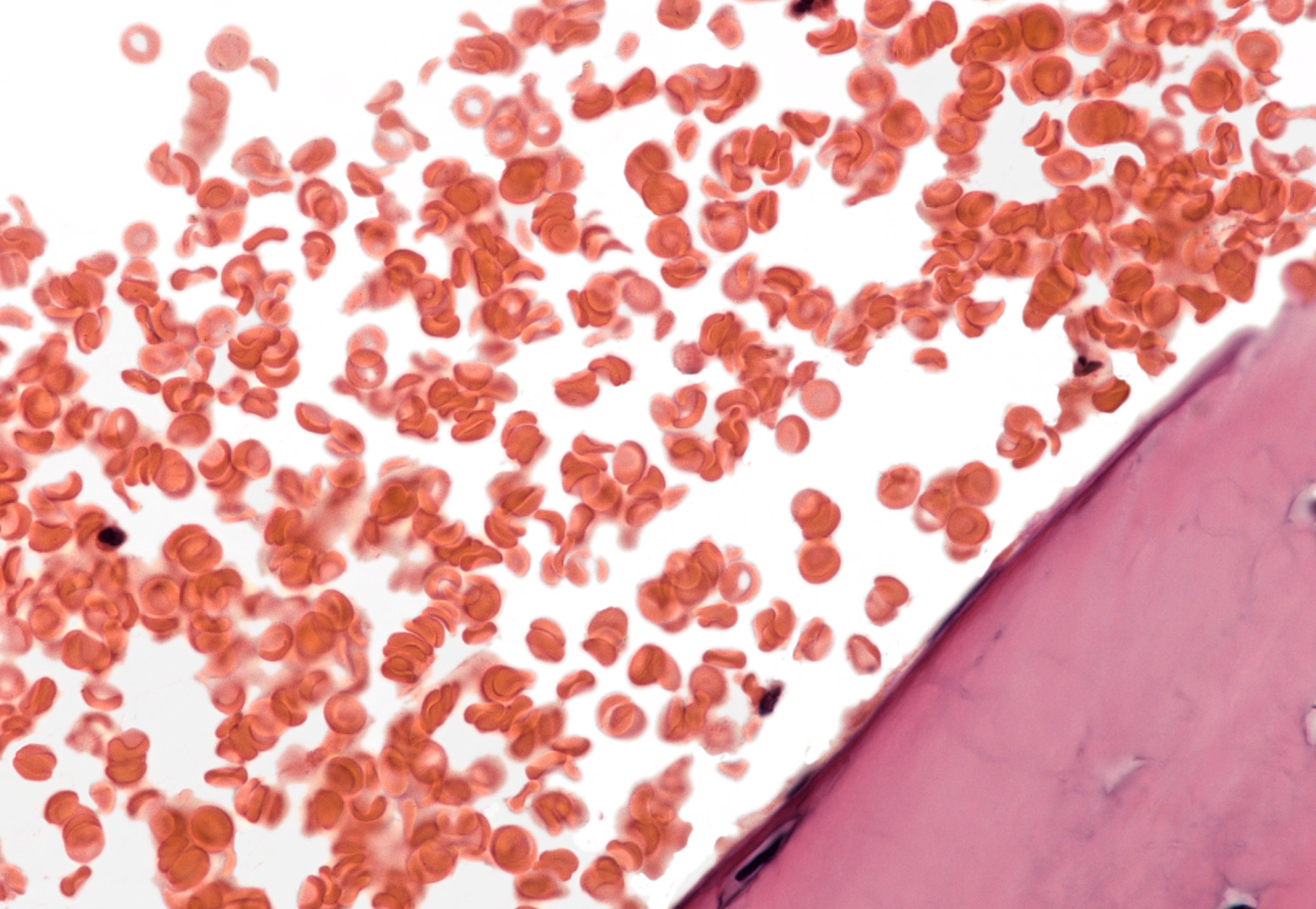

Our bodies needs iron to make haemoglobin, which helps carry oxygen through your blood to all parts of your body. Anaemia occurs when the level of haemoglobin is low. Research shows that reduced oxygen supply to the brain can lead to cognitive impairment and increase the risk of dementia in the elderly.

Our research looked at the use of PPIs in more than 50,000 people and analysed the difference in time and dose-response between patients with iron deficiency and a control group without it (a technique called case-control study).

We calculated the duration and daily dosage of PPI use based on records of prescriptions and compared these between the two patient groups. We found that people who used PPI continuously for one year or more had a higher risk of iron deficiency than people with continuous PPI use of less than one year.

Health & Medicine

Saving lives with less blood

People using one 20 milligram tablet of PPI or more daily had a higher risk of iron deficiency compared with people who were taking less than one tablet daily. We found a much higher proportion of patients with iron deficiency who continuously or intermittently used PPIs compared to people without iron deficiency.

Even with other potential factors that can also cause iron deficiency ruled out, like blood loss, chronic diseases and malabsorption of foods, continuous use of PPIs for one year or more still increases the risk of iron deficiency.

HOW PPIs WORK

The mechanism by which PPIs suppress gastric acid production is quite complex.

The lining of the upper part of our stomachs contains the so-called parietal or oxyntic cells, which are responsible for secreting hydrochloric acid.

This acid production process requires the help of an enzyme that pumps hydrogen ions out of the parietal cells in exchange for potassium ions. Because hydrogen ions are classified as protons, this enzyme is known as a proton pump.

PPIs work by inhibiting this enzyme and hence inhibiting the formation of hydrochloric acid.

Because this inhibition occurs at the final step of acid secretion and cannot be reversed, PPIs are remarkably effective and can reduce acid production by up to 80 per cent. But because the majority of dietary iron exists in an insoluble form, without acid, it won’t be absorbed properly.

Sciences & Technology

More than just strong bones

And this potentially leads us to anaemia.

At the moment, clinical guidelines don’t have recommendations for routine monitoring of body iron status in patients taking PPIs.

The latest guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease from the American College of Gastroenterology indicate that, when they were written in 2013, there was no data showing the development of iron deficiency anaemia in normal individuals receiving PPI therapy.

The most recent expert review and best practice advice on the risks and benefits of long-term use from the American Gastroenterological Association in 2017 doesn’t include iron deficiency in the summary of potential adverse effects of PPI use, and says screening for iron deficiency in long-term PPI users has no proven benefit.

However, our research suggests that doctors should consider iron deficiency as one of the important adverse effects of PPIs when balancing their benefits and harms. The dosage and length of PPI use should be appropriately reduced as much as possible.

Monitoring body iron in patients who have been on PPIs for a year or more is also necessary, especially in patients with suspected symptoms of iron deficiency.

There are also several emerging studies showing harmful effects of PPIs such as gastric cancer, and it’s crucial that doctors remain vigilant when prescribing PPIs for long-term use.

This will help not only to improve patient outcomes, but also to reduce the economic impact of these widely prescribed medications, which cost Australians over $400 million between 2006 and 2007.

It’s time to examine the cost-effectiveness of different dosages and lengths of PPI use and balance their benefits with their potential harms.

Banner: Getty Images