Politics & Society

US tariffs have backfired, and China is winning in Southeast Asia

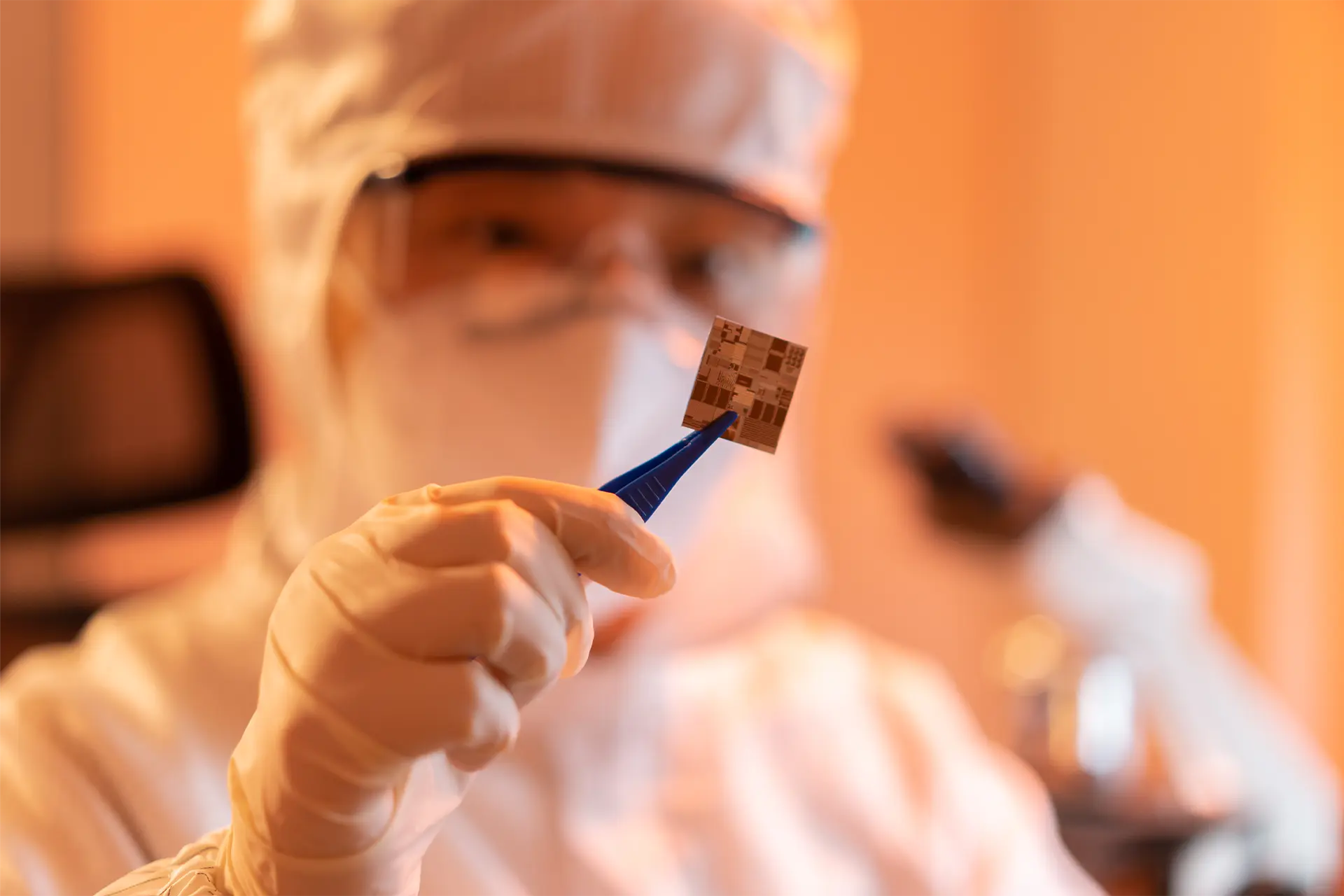

China’s semiconductor chip industry is decentralised, politically curated and immune to single points of failure

Published 8 May 2025

As Donald Trump threatens a second wave of ‘reciprocal tariffs’ – not just on China, but on Southeast Asian countries allegedly helping Beijing dodge US sanctions – a new chapter in the global chip war is unfolding.

But while Washington clings to old models of tech dominance, China has quietly rewritten the playbook.

Forget national champions, China’s semiconductor ecosystem thrives on fragmentation, not consolidation.

Semiconductor chips are the information processors that run computers, AI servers, electric cars, phones and most electronic devices.

In place of a single Intel or Nvidia, Beijing has built a sprawling battlefield of domestic chipmakers: Loongson, Huawei, T-Head (Alibaba) and others.

These firms don’t coordinate – they compete fiercely within a state-engineered architecture, where survival hinges on alignment with state priorities, policy coherence and validated performance.

To outside observers, China’s chip strategy might look chaotic. Multiple vendors, rival architectures, overlapping products – it seems inefficient.

But this fragmentation is engineered, not accidental.

Politics & Society

US tariffs have backfired, and China is winning in Southeast Asia

In the face of escalating techno-containment – a coordinated US campaign to sever China’s access to advanced chips, design tools and manufacturing equipment – Beijing has responded with a doctrine of techno-independence.

Rather than aiming for profitability, efficiency or market share, China has built redundancy into the system.

Loongson supplies Central Processing Units (CPUs) for secure desktops and state servers. T-Head’s chips power Alibaba Cloud during national-scale events like the Double 11 shopping festival.

Huawei’s Ascend processors now train large AI models like DeepSeek, replacing NVIDIA’s H100s banned under US export controls. Loongson chips are even deployed in BeiDou satellites and aboard the Tiangong space station, highlighting their versatility in both terrestrial AI and workloads needing radiation-hardened reliability.

Each firm operates in a defined lane. Each is filtered through a set of institutional gates: Document 29 procurement rules, indigenous innovation (Xinchuang certification) and access to the Big Fund, China’s strategic semiconductor investment arm.

The result?

A chip ecosystem that is decentralised, politically curated and immune to single points of failure.

Trump’s tariff plan is grounded in an assumption that China still depends on foreign technology and global supply chains.

But that logic is outdated.

Since 2018, Beijing has systematically hardened its domestic technology stack.

In 2024, Loongson shipped 10,000 3A5000 CPU-powered computers to schools in Hebi city, signalling mass-market readiness. T-Head’s Yitian 710 chip now anchors high-load applications in e-commerce and cloud AI.

Huawei’s Ascend 910C powers AI systems are used by Baidu and iFlytek – systems once dominated by US hardware.

These deployments aren’t aspirational; they are operational.

China’s tech firms are no longer trying to dominate global markets – they are building functional sovereign infrastructure.

Politics & Society

How construction technology can help solve Australia's housing crisis

In the US, innovation is judged by quarterly earnings, market share and investor sentiment. Venture capital fuels speed, not staying power.

The result is a tech ecosystem optimised for disruption, but vulnerable to supply shocks and geopolitical ruptures.

China plays a different game. Innovation is judged by strategic fit and institutional trust.

The state doesn’t ask: “Can this chip beat Intel?” It asks: “Can this chip securely run Kylin OS in a state server, independent of foreign code and sanctions?”.

China is not chasing the technological frontier – it is building fit-for-purpose solutions that meet national security standards and deliver strategic autonomy.

Performance matters, but resilience matters more.

What emerges is not a race to global tech dominance, but a strategy of techno-independence: one that rejects the volatility of market cycles in favour of a hundred-year horizon, where innovation is a pillar of state sovereignty, not a quarterly metric.

As global supply chains bifurcate, China’s chip strategy offers a model of distributed autonomy.

No single chip architecture – LoongArch, ARM, RISC-V, x86 – is indispensable. No firm is too big to fail.

By distributing risk across multiple platforms and vendors, Beijing has insulated itself from the kind of chokepoint dependencies that once made sanctions effective.

This is where Trump’s second-term strategy may misfire.

Reciprocal tariffs assume China’s tech ecosystem is brittle and externally reliant. But fragmentation has made it resilient – capable of absorbing shocks and regenerating internally.

While Washington is busy guarding the gates, Beijing is building tunnels.

In China’s chip sector, fragmentation is not inefficiency – it is industrial doctrine. It ensures that no single export ban, legal challenge or foreign embargo can cripple the system.

Politics & Society

One word is missing from this Australian election. It’s Asia.

By requiring firms to compete for state validation, China builds not just chips but also trustworthy infrastructure aligned with long-term national goals.

This model isn’t designed to win the next product cycle. It’s about winning the long war for technological independence.

While Australia has rejected integrated Chinese platforms like Huawei’s 5G over national security concerns, the fragmentation of China’s tech stack calls for a more nuanced response.

Some Chinese-developed systems, like open-source RISC-V processors or open-source AI models, offer potential for low-risk, selective engagement.

The challenge is no longer about choosing sides, but about navigating a fractured ecosystem where resilience, not reflexive alignment, should guide policy.

Even in an era of suspicion and division, as geopolitical strategist Philipp Ivanov notes in his Strategy 2025 analysis, for Australia, strategic agility may prove more valuable than blanket exclusion.