Human vs computer: Becoming more employable than an algorithm

There is global unease that technology could leave many of us redundant, as jobs are taken over by computers. But it could, in fact, free us up to use our very human skills of creating new knowledge, problem solving and working collaboratively

Published 6 October 2017

Human vs computer: Becoming more employable than an algorithm

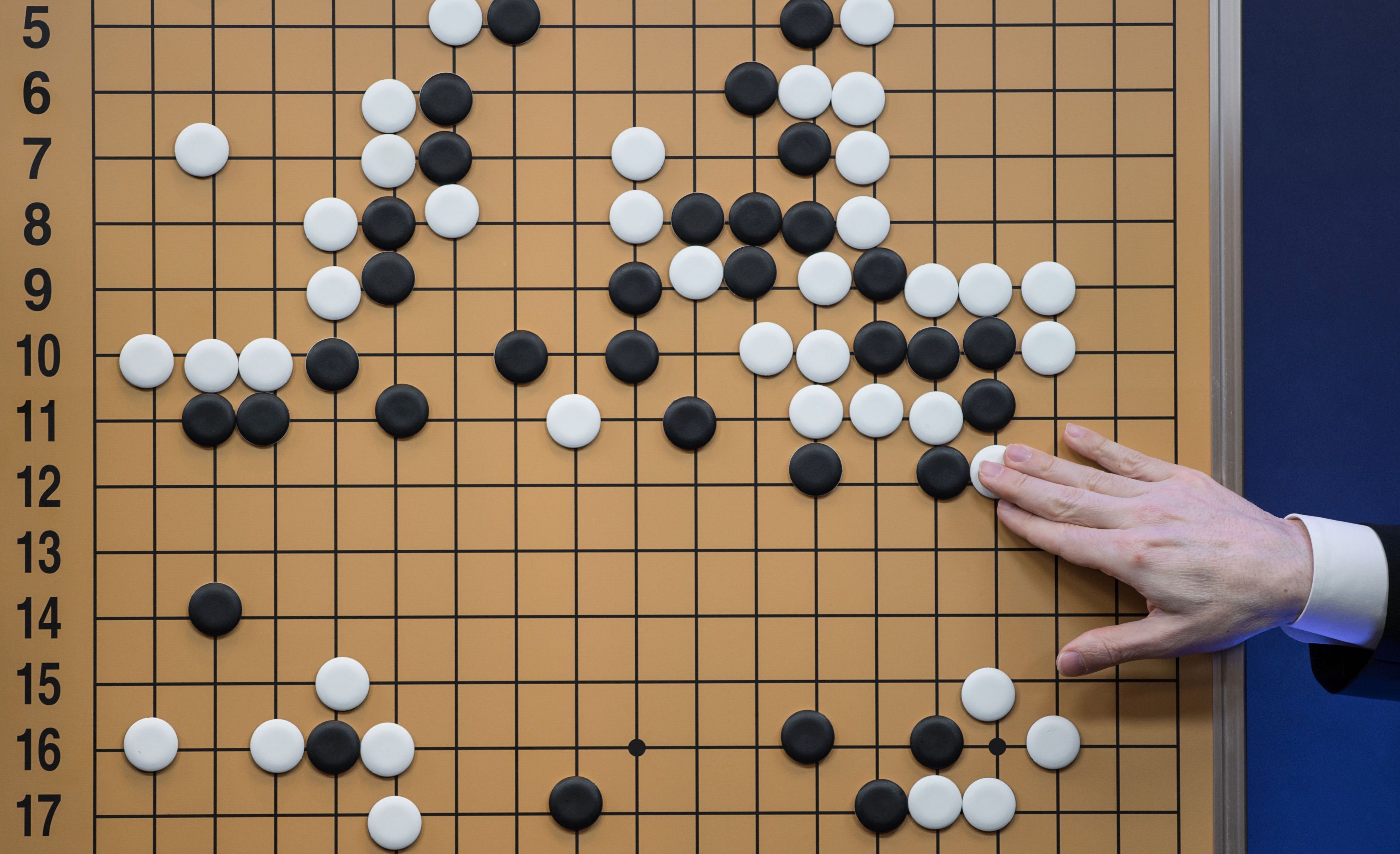

Chinese philosopher, Confucius, praised Go as the only game worth playing. Originating in China at least 2,500 years ago, Go is a simple game of encirclement but one with a strategy deeper than chess, requiring both analytical skill and intuition.

Its subtleties are such that in 1997 a US astrophysicist famously told The New York Times that “it may be a hundred years before a computer beats humans at Go’’. He was wrong. It took just 20 years. In May, Google’s AlphaGo computer beat the world champion 3-0 having humbled a famous grandmaster along the way.

If a Go grandmaster isn’t safe from a machine, is anyone?

Forecasting the future

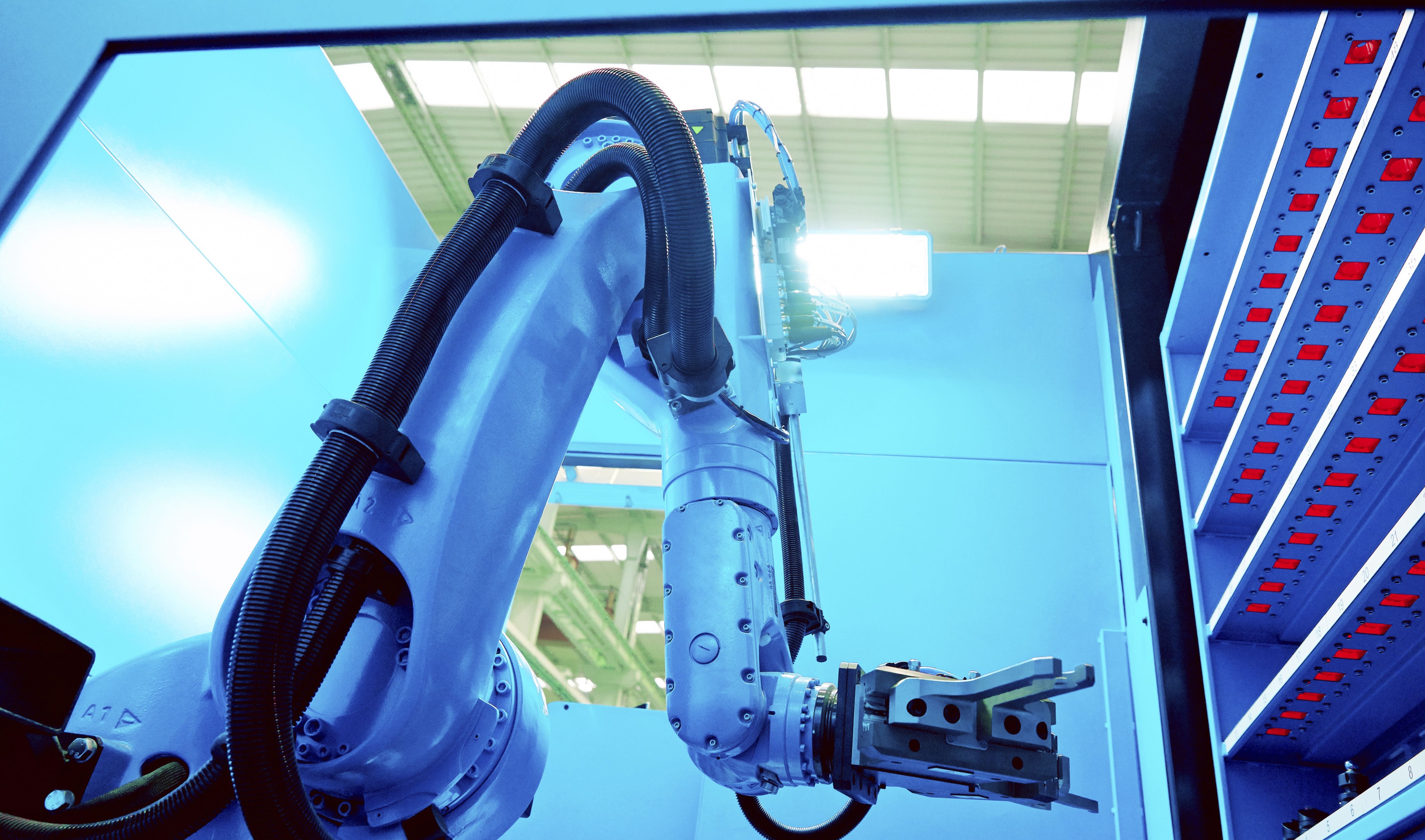

Computers have quickly moved from providing pure processing power to learning and adapting without programming, creating widespread unease that the rise of the machines will leave many jobless. In 2013, Oxford University research suggested that within the next 10-20 years some 47 per cent of US jobs will be at risk of being replaced by computers and algorithms.

“Computers have moved beyond their previous constraints when they could only be programmed to do codified tasks, and we are now finding examples of computers being able to do work we never thought could be automated, whether it’s writing a news story or diagnosing health conditions,” says Dr Josh Healy, from the Centre for Workplace Leadership at the University of Melbourne.

But Dr Healy says the future of work isn’t as bleak as some of the more alarmist forecasts. It is a more nuanced future in which the unique skills of humans will be even more valued than today. It means the urgent policy problem won’t be job creation, but instead ensuring people are equally equipped to share in this future.

“Since the Industrial Revolution 200 years ago, technological advances have always led to job destruction, but more new jobs have always been created. At this stage, there is no clear evidence this will be any different to what has gone before. We aren’t eliminating work, unemployment rates aren’t blowing out, work isn’t disappearing,” says Dr Healy, a labour and workplace relations academic.

Who are the winners?

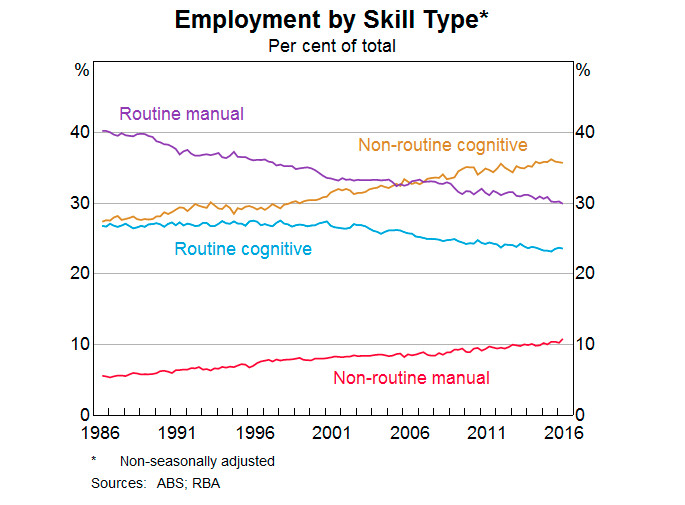

But work is changing. In developed economies, the share of routine manual work has been falling gradually for decades and more recently the share of routine cognitive work has also started to fall.

Computers are replacing work like data entry, document searching and formulaic report writing. Programs can now even provide routine step-by-step legal and financial advice. In contrast, non-routine manual work like child and aged care is showing signs of growth, while the big winner is non-routine cognitive work - this includes jobs in the health care and social assistance sector, professional, scientific and technical services, as well as education and training.

A recent estimate from the Reserve Bank of Australia of the changing Australian employment market over the last 30 years provides a strong illustration.

Similarly, the Foundation for Young Australians analysed 4.2 million early career job ads between 2012 and 2015 and found that the demand for digital skills had risen by 212 per cent. Demand for critical thinking skills grew 158 per cent and demand for creativity grew 65 per cent.

Learning literacy 4.0

The trends are stark, but Dr Healy says rather than suggesting mass human redundancy, what we are facing is a shift in the type of work people will be doing.

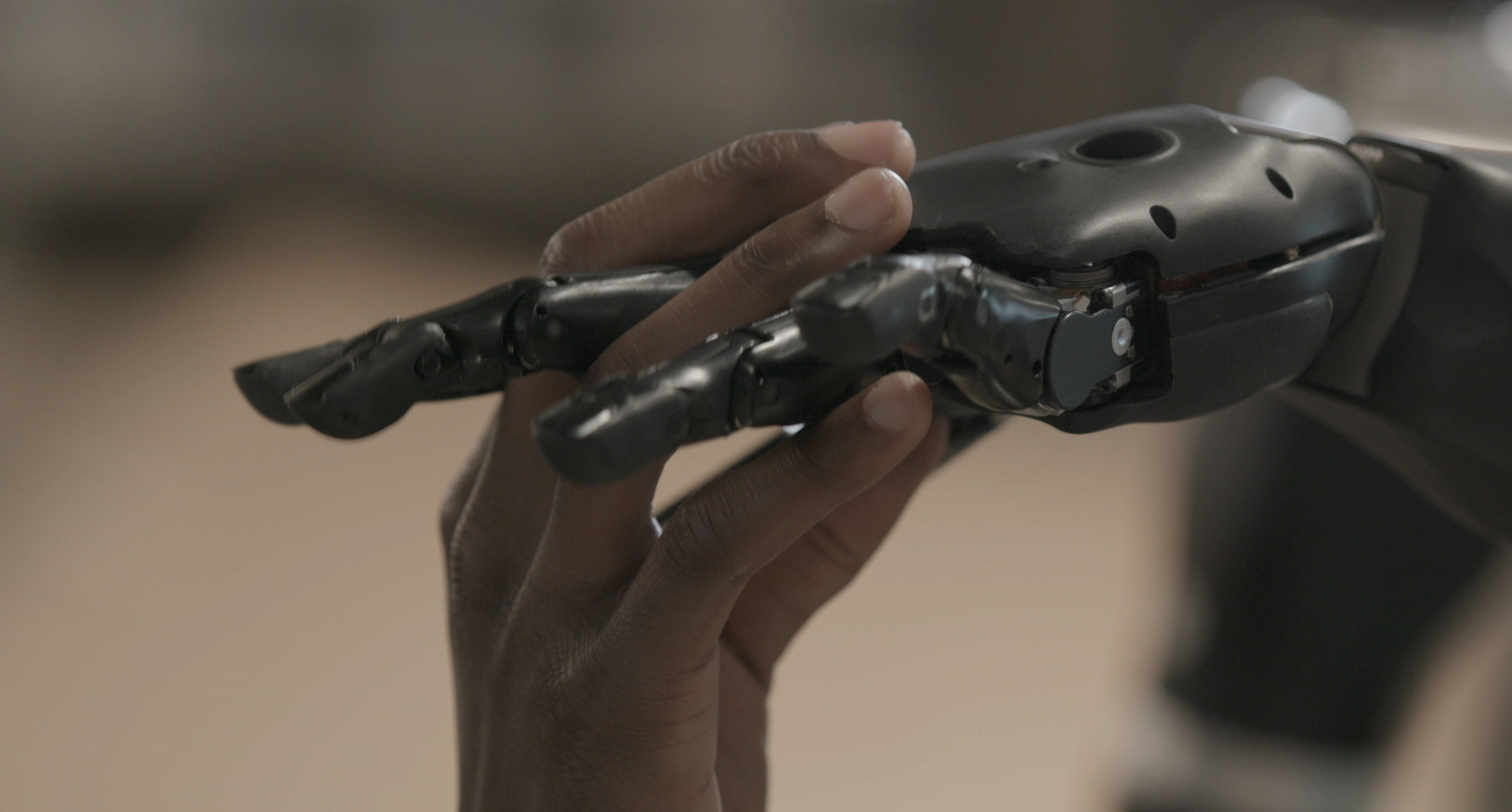

“While these technological developments will touch most of us, the impact on most jobs will be around the edges,” says Dr Healy. “We will start to see portions of jobs being hived off to increasingly capable machines, but that will free up people to focus on non-routine work that machines struggle to do. This is the sort of work that isn’t predictable, where people have to exercise discretion, judgement and creativity in what they do, and where they have to collaborate.”

It is what researchers are calling augmented work.

“People will still need to know the technical aspects of technology and how it works, and they will still have to have diagnostic abilities that come from a grounding in a discipline,’’ says Dr Healy. “But there will be a new value on taking the output of technology and being able to use it to create, for example, a specific client brief, or use it in a courtroom, to design something, or be able to interact with people, be it co-workers, customers or patients.”

But these non-routine skills are all highly dependent on language, especially digital text communications that education researcher Professor Lesley Farrell says is driving the creation of a whole new type of literacy. Just as the new digital technologies are being called the fourth industrial revolution, researchers are calling the new literacies Literacy 4.0.

“The smart factories and workspaces that are emerging rely on automation and artificial intelligence, and the human tasks are focused on creating new knowledge, problem solving and working collaboratively,” says Professor Farrell, Dean of the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education.

“These workplaces are using online crowdsourcing platforms to solve problems and engage workers, including freelancers, in specific micro-tasks.

“All this work is heavily text-based, involving writing, reading, speaking and listening. But it is a new type of literacy that is conversational and focused on creating relationships, and it’s a literacy that we simply haven’t been training people for,” she says.

Professor Farrell notes that US-based Local Motors, which operates a smart factory model in Arizona to produce customised vehicles, uses an open crowd-sourcing platform to solve problems, offering prizes for solutions.

“To engage on such a platform and gain work at somewhere like Local Motors, it simply won’t be enough to be a brilliant metal worker. You’ll have to be able to engage in these conversations, understand your audience and present an identity that expresses competence and confidence. These are all very sophisticated skills,” Professor Farrell says.

Ensuring you’re not left behind

Dr Healy says ensuring that people aren’t left behind is going to be a “huge socio-economic problem”.

“While the future of work to some extent might look reassuring for a skilled professional class and perhaps also for care workers and those jobs demanding human interaction, the future is a lot less clear for routine work and the routine workers who are losing their jobs,” he says.

“We will have to think harder about how government can provide more spot assistance to people when they need it, to help them bridge these transitions between work such as income support and retraining,” says Dr Healy.

“We will also need to counter employer bias against older workers, and to encourage workers generally to look wider for opportunities to use their skills.”

For example, the Foundation for Young Australians has identified seven wide “clusters” of job types in Australia, within which there will be a range of different jobs that people will be able to do. They define these clusters as “generators”, “artisans”, “carers”, “informers”, “coordinators”, “designers” and “technologists.”

So, what should we be telling young people?

“I would be encouraging them to be curious and make it normal for them to focus on a problem and find a way to solve it,” says Professor Farrell.

“These changes in the way we work will affect our relationships, our intellectual life, our ideas of work-life balance, and how we engage in the public sphere as citizens separate from our work.

“So, in a sense people will need to learn how to be a whole person in a world where work is changing and will continue to change throughout their lives.”

Banner image and video: Getty Images