Arts & Culture

The hidden stories in Australia’s cultural data

Defamation laws are having a chilling effect on non-fiction so those keen to get behind a story like Depp v Heard are likely to be left wanting

Published 8 August 2022

Depp v Heard followers will be disappointed to learn that this is probably where the drama ends.

While a celebrity’s ‘rough patch’ can sometimes provide for a juicy memoir, the outcome for Heard in this highly publicised case indicates that the chilling effect of the threat of defamation is still a very real obstacle for freedom of speech.

For trade book publishing, this can be a real dampener in a thriving non-fiction market. Particularly in Australia, where defamation law is notoriously complicated, the road ahead looks unnavigable. Or is it?

Australian readers love non-fiction as much as fiction. We like to know the juicy details about people, both public and private, and the truth of ‘what really happened’. However, retelling what really happened can cop you a lawsuit, as is evidenced by an historical snapshot of affected Australian titles: Bob Ellis’s Goodbye, Jerusalem and Goodbye, Babylon, which were eventually pulped; Anne Coombs and Susan Varga’s Broometime, which was reprinted; and Judith Moran’s My Story, which was withdrawn by publisher Random House.

Arts & Culture

The hidden stories in Australia’s cultural data

Journalist and author Kate McClymont’s book He Who Must Be Obeid was pulped in 2014 and republished with edits, prompting her to comment that ‘Whenever I do a story, in the back of my mind is a lawsuit’.

The Australian edition of Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill, which documented how Farrow exposed the abuse of disgraced Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, also faced challenges. The New York Times reported that ‘lawyers for Dylan Howard, an executive with American Media, Inc., sent letters to Australian booksellers … warning of ‘false and defamatory allegations’.

The upshot of this for publishers wanting to avoid litigation is a tendency towards ‘implicit censorship’ – a process of pulling titles from lists before they get too deep into the editorial process, or circumventing the potentially defamatory content by ‘editing out’ the problematic passages.

This type of editing has been described as difficult to identify because it is work that happens behind the scenes by way of ‘textual cuts’ and other subtle editorial manipulations.

While this activity might sound like censorship, it isn’t technically the same as censorship of ‘blasphemous’ or ‘seditious’ works for which there are codes of conduct to alert readers. Rather, ‘implicit censorship’ is a kind of duty of care whereby an editor helps to find the balance between risk and expression.

This is especially important in Australia, where defamation law has traditionally been clearly tipped towards protecting reputation. Its practice, however, raises questions about whether the Australian publishing industry promotes a culture of caution that might have a significant impact on our reading satisfaction.

Arts & Culture

Measuring diversity in Australian publishing

Matthew Collins AM QC has described Australia’s defamation laws as a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’, given its patchwork development over the years – crafted in an attempt to both protect reputation and facilitate freedom of expression. But there are a few distinct obstacles that have set the Australian situation apart from other jurisdictions such as the US.

Until recently, there has been a lack of consideration for editorial input and assessment. Australian defamation law has also protected the reputation of the claimant even when their activities might have a public interest element.

Even public interest defences, which propose to mitigate the chilling effect, often fail. Qualified privilege, for example, provides some reasonableness guidelines for journalistic commentary and a standard of good journalistic practice, which might assist in determining if, in the absence of a defence of truth, a publication could still be protected from litigation. However, verifying facts and seeking a response from the person being reported on is not always possible.

Additionally, the defence is often reserved for journalistic writing, which can be quite different from non-fiction publishing with its longer publication lead times.

These obstacles have prompted the NSW Government to explore solutions over the past few years. On July 1st 2021, defamation law reforms were announced to help steer the law towards being more flexible, particularly in this digital age.

The most interesting of the developments for commercial publishing is the new public interest defence, which is modelled on section 4 of the UK Defamation Act and which allows for editorial assessment into whether the statement/s made are in the public interest.

While this sounds promising, it can really only be applied successfully to mass media journalism and political commentary, and there is still a discernible grey area around celebrities and other persons of interest.

Readers’ fascination with individuals in the public sphere also expands the array of authors with varying degrees of writing experience – some might be professional journalists or highly regarded fiction authors who have included in their work non-fiction elements and/or investigative-type writing. The expertise of the writer might also be scrutinised when factoring in editorial assessment.

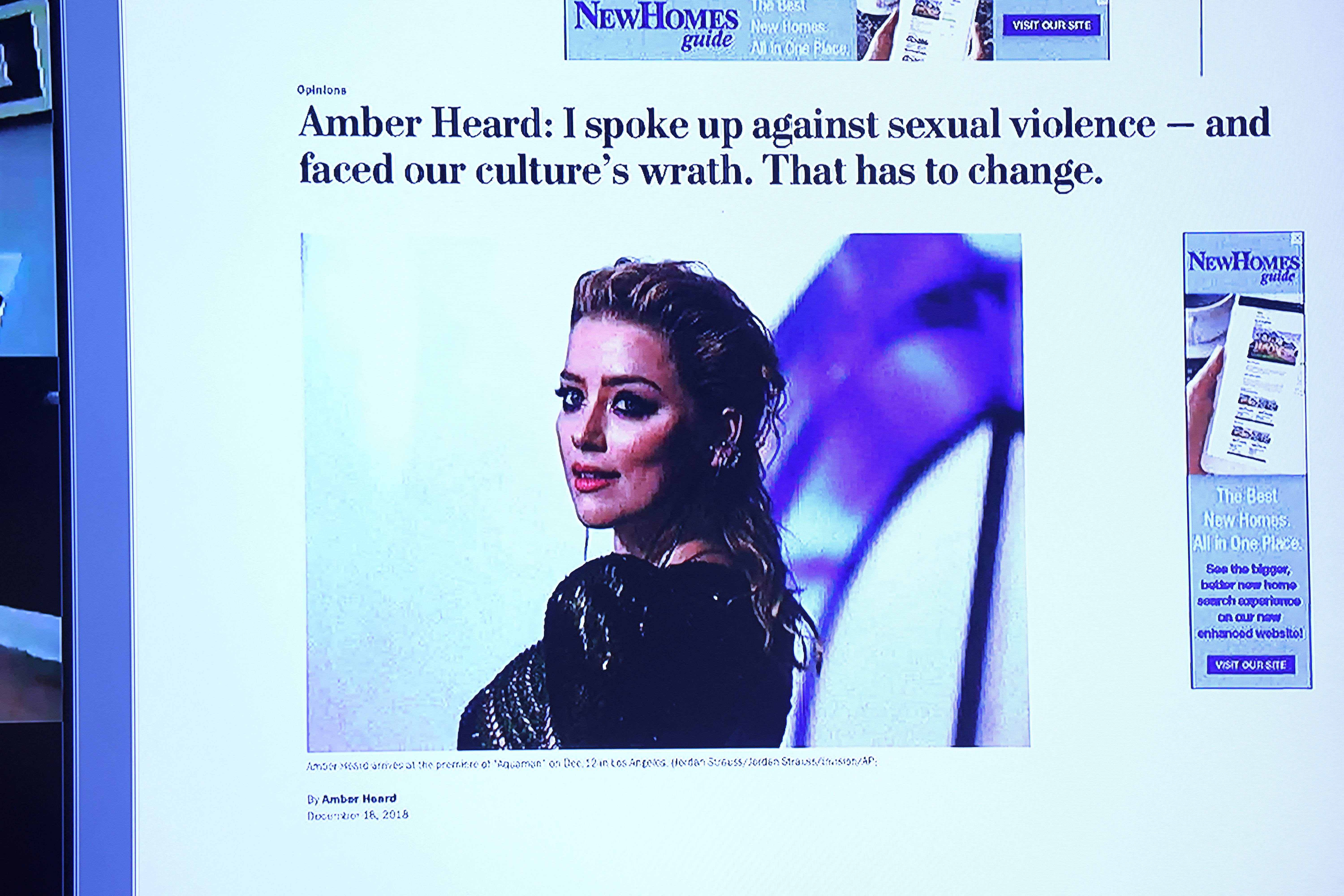

While the law has moved forward incrementally, we still haven’t ascertained what a person in the public interest looks like from a legal perspective. Even in Heard’s op-ed for the Washington Post, for example, the supposed imputations were enough for Depp to claim the piece had referenced him – a public person, even though he is never mentioned.

Notwithstanding the many other legal factors to be taken into account in the Depp v Heard situation, the publication of the content was the most contentious point of conflict. So where to from here?

Earlier research into the extent of self-censorship in Australian journalism, comparing the Australian situation to the US, found that journalists tend to water down content, to convey ‘elements’ but not the ‘guts of it’.

While the new public interest defence appears to help address implicit censorship, it is yet to be seen whether it will have a significant impact on how non-fiction book publishing is treated editorially in cases where the content is likely to affect a person’s reputation.

With ‘public interest’ still a vague term, my guess is that it will, and that its implementation has ongoing consequences for freedom of expression and Australian non-fiction publishing overall.

Banner: Shutterstock