Politics & Society

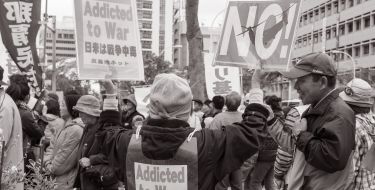

Protest and democracy in Asia

Pita Limjaroenrat may have won Thailand’s elections, but he isn’t Prime Minister. He says he’s still hopeful his country will become a true democracy, without the military in government

Published 28 June 2024

Thailand’s monarchy and military exert a huge influence on government.

Since the nation was declared a constitutional monarchy in 1932, there have been 12 coups (and more attempted), the most recent in 2014.

Democratic advocacy organisation, Freedom House, currently rates Thailand as ‘partly free’, giving it credit for holding competitive parliamentary elections in May last year. But the result of the elections has demonstrated the continuing strong influence of the military and royalist forces.

The reformist Move Forward party won the most seats in the House of Representatives and looked to be able to form a majority through a multi-party coalition.

But the Party’s leader Pita Limjaroenrat has been blocked from becoming Prime Minister and the Move Forward party may be dissolved by authorities.

The Harvard-educated businessperson is also facing being banned from public office for 10 years over his party’s intention to reform the lèse-majesté law which prohibits criticism of the monarchy.

Mr Limjaroenrat spoke with Melbourne Asia Review’s managing editor, Cathy Harper ahead of delivering the University of Melbourne’s inaugural Southeast Asia Oration.

Politics & Society

Protest and democracy in Asia

Q. Given the election result, what are your plans for the future of your party?

To move forward. Either under the same brand name, same political party, same colour, or in a different political vehicle under a different name, but the ideology and the platform will continue.

It’s a tragedy that we’re talking about this, the second time in five years and five times in 20 years.

For me and for my party and my MPs and a lot of our supporters, whether it’s inside Thailand or observers from afar such as diplomats from various countries, are thinking of this as a way to save the democratic space in Thailand to make sure that the boundaries between executive, legislative and judiciary are balanced.

It’s quite easy to slap some cases against political parties or political leaders who are elected.

A lot of ‘independent’ organisations that have been used to slow down the pace of change have no accountability to anyone. Independent of whom, independent of what? It might be independent of the people, but very dependent on a certain elite or certain individuals – and we don’t want that to be the case in Thailand.

Q. Do you think that Thailand’s former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra is actually a kind of de facto Prime Minister?

We do a lot of data analysis, we do a lot of social listening tools and we see that the frequency or the velocity or the size of the appearance of Prime Minister Thaksin is equivalent, if not more, than the current Prime Minister.

And lot of interviews that were given contradicted the current Prime Minister.

It’s understandable why the media or the people are starting to question the leadership of the current government, who really runs the government and if there are two tigers in one cave then what happens?

Politics & Society

Is our democracy broken?

Q. How do you see the alliance between the Pheu Thai party (Thaksin Shinawatra’s political party) and the military being sustained?

A flip-flop alliance. The people of Thailand deserve to know who you will form a coalition with.

We said “we don’t want the military dictator to be part of our coalition”. Pheu Thai also said the same in a debate but they U-turned and they formed an alliance with the military.

That’s in the past, I know, it’s been almost a year. But what remains today is how they entered power.

For example, you want to end military conscription and use the military budget for something else such as climate change.

But because the way you entered power was by U-turning and destroying your legitimacy, and you formed government with the military who ousted you, and who staged two coups against you, you [cannot] exercise the policies that you promised the voters.

You couldn’t do it because the military is part of your government.

It’s not just me being glum or being really bitter about the past year. It effects Thailand today and it will affect Pheu Thai and the military going forward as well.

We have various political policies hoping to end the cycle of military coups, such as a civilian government, making Thailand part of the International Criminal Court so there is international scrutiny when it comes to these things, putting in the Constitution the inability to grant amnesty by the military to themselves – so nobody can prosecute them.

Politics & Society

As the US elections near, global democracy is at stake

People cannot accept the normalisation of coups.

It’s happened 12-13 times since 1932 and they feel like if there’s going to be violence on the streets they might as well just let the military come in; at least they are not going to be corrupted like politicians.

But in the past 10 years it has been proven again and again that the corruption index is going downhill even if there is the military.

For someone who is trying to ride a bicycle of democracy, it’s not always going to be a straight line.

There may be zig zags and you will probably fall a couple of times, but you are going to let the institution find a solution rather than having the military kick you off the bike and they take the driver’s seat.

Q. The result of the election last year shows that a reformist agenda is attractive for a lot of people. How do you reconcile your reformist plans with the reality of having to form power? Did you take a too ‘purist’ approach?

We tried to reform with confidence and the result speaks for itself. We’re not trying to change Thailand to something that is beyond their imagination.

I planned short, medium and long term. We said what we wanted to do in the first 100 days, the first term and the second term.

A lot of things that might seem very radical to a lot of people we said very clearly, very precisely, very objectively, that is not going to be done in the first year or two.

These kinds of things are hard to digest for people and obviously a lot of fake news operations and information operations by the military themselves or by some other people.

But if you change too slowly that means other people are going to change it for you.

Politics & Society

Searching for Democracy 2.0 without losing Democracy 1.0

Q. I wonder if you could reflect on the state of democracy in Southeast Asia which has been in decline in many nations over recent decades?

It’s backsliding and fragmented. It’s not perfect in any country, but some are flourishing, and some are not.

In Cambodia you have the demolition of the Candlelight Party. In Myanmar you have the risk of not being able to imagine what the post-conflict Myanmar would look like.

In Thailand it is, as you said, a judicial soft-coup and an attack on democracy. In Indonesia, the Philippines also, there is a question about political dynasties.

But I feel like it’s really important for the ASEAN communities and us to really stick together in terms of solidarity because there is a slippery slope that once something happens to one country it impacts another.

Q. What do you think of the view that is quite often expressed, but is perhaps a cliché, that the Asian public likes strong leaders? Do you think that’s true?

I think it’s true all around the world. I just came back from Berlin and that’s also the case.

I guess it’s because of the rhetoric that is going on around the world – two wars as well as the pandemic that we went through, as well as stagnant economic growth.

The progressives, including myself, have to be much smarter and much stronger and also show the people that leadership is not just about fear. It can be about hope and it can be about working together with the people and it can be about empathy.

My favourite leader in the world who I look up to is Jacinda Ardern.

I think she proved to the world during the COVID crisis and during the Christchurch massacre that you don’t have to be a ‘strongman’ with fear tactics and a militant background to resolve crises for the country.

We progressives have to be smarter and stick together, and make sure the world doesn’t turn any more ‘right’ than it is – especially this year when there are a lot of elections going on.

This is an edited extract of an interview with Pita Limjaroenrat, the full version is available at Melbourne Asia Review.

This interview is part of an Asia Institute and Asialink series on democracy in Southeast Asia. It was recorded ahead of the inaugural Southeast Asia Oration at the University, to be delivered on 4 July by Mr Pita Limjaroenrat MP, a Member of the Thai House of Representatives and Former Leader of the Move Forward Party.