India builds for future with climate plan

The Asian powerhouse is forging a path to climate resilience, embracing technologies such as solar power on a massive scale

Published 26 November 2015

India’s current rapid transition towards a low-pollution and climate-resilient future constitutes one of those rare moments in global politics where national and international identities (and interests, therefore) significantly align.

This compatibility presents a window of opportunity for leaders of developed and developing nations to come together at the upcoming United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations in Paris and hammer out a strong global agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The policy and language of transition in India

India, under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is currently undergoing a rapid transition towards a low-pollution and climate-resilient future. This transition is primarily being operationalised in its electricity, agricultural, cities and urban transport sectors.

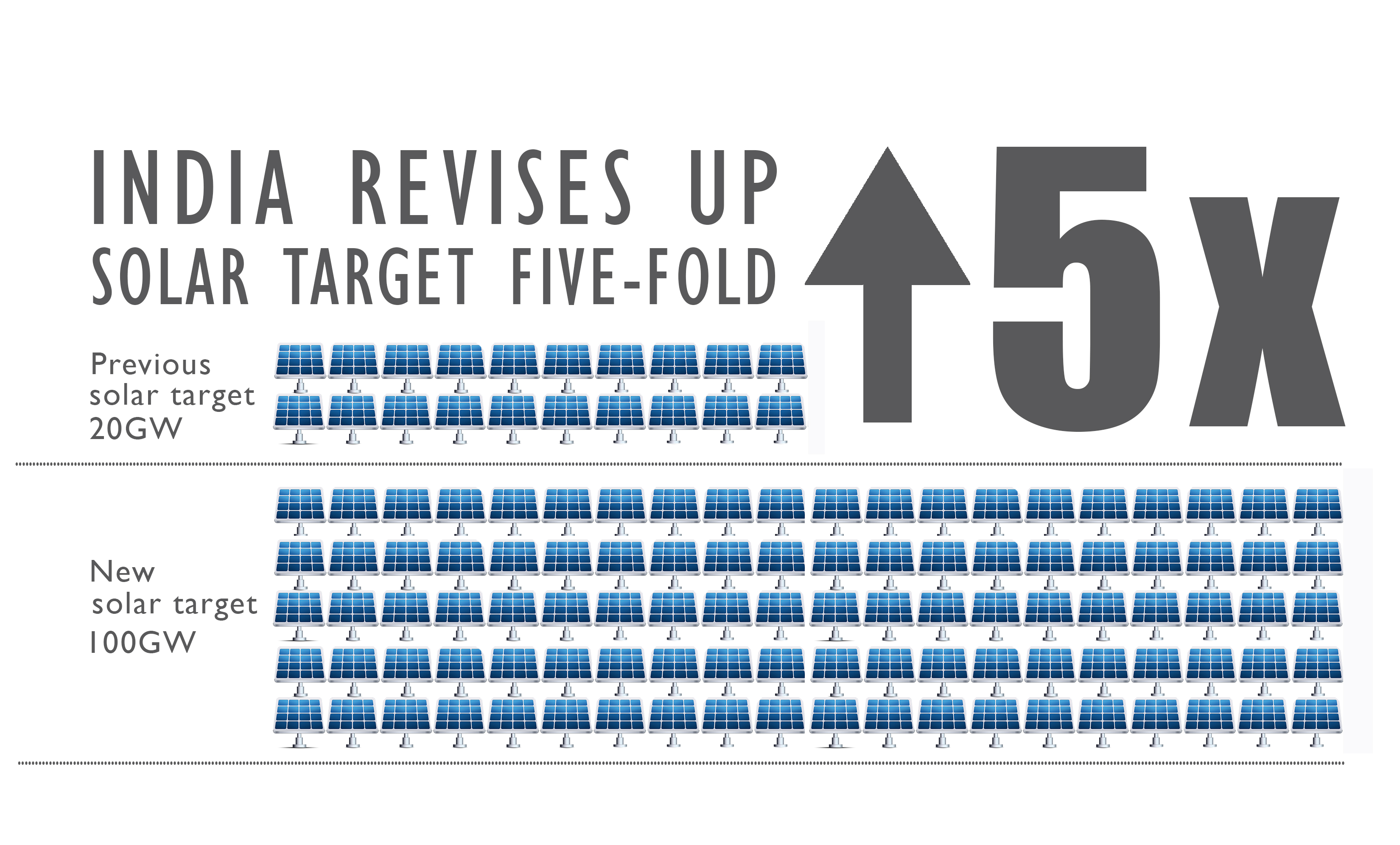

In terms of electricity, as recently as 17 June 2015, the Modi Government approved a five-fold increase in India’s solar electricity target – up from 20 gigawatts to 100 gigawatts by 2022. This is an ambitious target and achieving it would see India surpass Germany as the world leader in solar.

Modi foretold of a shift in India’s electricity mix while on the election campaign trail in 2014: “The time has arrived for a saffron revolution,” he declared, “and the colour of energy is saffron.”

In terms of agriculture, also in June 2015 Modi called for “a second agriculture revolution” to ensure India is prepared to adapt to increasingly erratic climatic conditions, including more frequent droughts, heatwaves and unseasonal storms, which requires, according to Modi, “changing the conventional and traditional way of farming … and making it more modern and scientific.”

He said: “Farmers practising traditional farming believe that unless their field is filled with water they cannot get good crops, but this may not be scientifically true because drip irrigation, irrigation through sprinklers are more effective and reduces of water and nutrients.”

In the cities and urban transport sector, in May 2014 Modi announced his vision to renovate 500 cities across the country and build 100 new “smart cities” from the ground up. This transition towards “clean and sustainable” urban spaces, the Government explains, is a core part of Modi’s plans for a modern India.

“Cities in the past were built on riverbanks,” Modi explains, “but in the future, they will be built based on availability of optic fibre networks and next-generation infrastructure.”

India’s transition: bringing benefits to India and the world

The Modi Government’s low-pollution and climate-resilient development plan has the potential to deliver a variety of social, economic and environmental benefits to India.

For instance, there are currently 300 million Indians that do not have access to electricity. Installing a cheap off-grid solar PV panel can help rectify this situation. The co-benefits of this approach to electricity generation are that it creates low skilled (installation) and high skilled (engineering) employment opportunities for India’s massive youth population (the largest in the world).

It also has the potential to avert many thousands of premature deaths from acute respiratory infections caused by smoke inhalation from indoor cooking and heating with biomass. Triple “wins” also exist in the agricultural and cities sectors.

As the world’s fourth-largest greenhouse emitter overall, India’s actions matter hugely to future global emissions. Indeed, the world needs India to develop cleanly to stand any chance of avoiding a 2 degree warming scenario, which scientists consider “dangerous” to breach.

National and international identities (and interests)

India’s rapid transition on climate change forms a key part of Modi’s broader efforts to construct a new “modern” identity for India, or as he describes it: to “refine, rebuild and transform the national character.” For Modi, India must no longer be known as a country that is “poor”, “old”, “unhealthy”, “unskilled”, “filthy”, and “underdeveloped”.

However, as one could expect, and as expressed in India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution lodged to the UNFCCC in October 2015, this transition will be expensive.

Indeed, the INDC estimates that more than $US 2.5 trillion (at 2014-15 prices) will be required to meet India’s climate change and development plan between now and 2030. While the Indian Government has allocated billions to these projects, and foreign investment has been forthcoming from major industrial countries such as the US and Europe, much much more foreign investment is needed for India to reach its climate goals.

The good news is that Modi’s vision of a “modern” India is largely compatible with the UNFCCC’s “action on climate change” narrative. As UNFCCC executive secretary, Christiana Figueres, explained in her opening address at the Twentieth Conference of the Parties (COP 20) in Lima: “The time has come to leave incremental change behind and to courageously steer the world toward a profound and fundamental transformation. Ambitious decisions, leading to ambitious actions on climate change, will transform growth – opening opportunity instead of propagating poverty.”

This is also consistent with key developed countries, such as the US. President Barack Obama said when visiting New Delhi in January 2015: “We very much support India’s ambitious goal for solar energy, and stand ready to speed this expansion with additional financing … no country is going to be more important in moving forward a strong agreement in (Paris) than India.”

Final thought

Modi requires international support from industrialised countries, through the UNFCCC mechanisms and separately, to fulfil his “dream” of a modern India. At the same time, the UNFCCC – along with key advocates for action on climate change such as the US, UK and Europe – require India to modernise cleanly to avoid dangerous global warming.

This overlap in identities and interests is positive news for advocates of a strong global agreement to be reached in Paris in December 2015, and its successful and ongoing implementation thereafter.

This article is based on a briefing paper published by the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, which is also publishing a blog on all the developments from the COP21 climate summit in Paris.

Banner image: Shutterstock