Health & Medicine

What you need to know about online genetic testing

Many of us understand how genes can pass on information through generations, but epigenetics is revealing how the effects of contracting an infection can be passed on to your children

Published 29 April 2020

The influence of parents on the lives of their children is complex.

Before we are born this influence is reduced to what can be inherited through egg and sperm. While the inheritance of genes shapes our physical features and predisposition to disease, it is now becoming increasingly clear that the legacy of a parent’s experiences can also be passed down – not through genetic changes, but through ‘epigenetic’ changes.

Rather than changing the ‘letters’ of our genetic code, epigenetics influences how this genetic code is ‘read’ by cells – they can change how genes are used, causing a slew of changes in cells, organs and the whole body.

One well-documented example of ‘epigenetic inheritance’ has been observed in the children of men who experienced extreme trauma. The children of Holocaust survivors show altered levels of stress hormones, an intergenerational legacy of the trauma of their parent.

These changes have been linked to factors passed on in sperm or eggs that subtly alter gene expression – despite the genetic code itself remaining unchanged.

Health & Medicine

What you need to know about online genetic testing

Interestingly, it has also been observed in men that epigenetic changes in sperm linked to obesity can be remodeled after undergoing surgical weight loss. This indicated that timely intervention can prevent these changes being passed on.

But what about infections? These can have long-lasting impacts on a person’s physiology, causing inflammation and tissue damage – but could the legacy of infections be passed to subsequent generations?

Our research has shown for the first time that male mice infected with a common parasite can impact their offspring’s brain health and behaviour – revealing how these epigenetic changes are transmitted between generations.

Toxoplasma is one of the world’s most common parasites, estimated to be carried by between 25 and 80 per cent of the global population.

Toxoplasma infection – which is often acquired from an animal carrier – can cause an initial mild illness in most people. But for pregnant women, babies and people with weakened immunity, it can cause more severe infections.

Cats are one species that can transmit Toxoplasma infection and that’s why pregnant women are advised to avoid contact with cat faeces.

Health & Medicine

Shaping the brain: Before, during and after birth

People can carry the dormant Toxoplasma parasite for decades, and this has been associated with the appearance of symptoms of mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

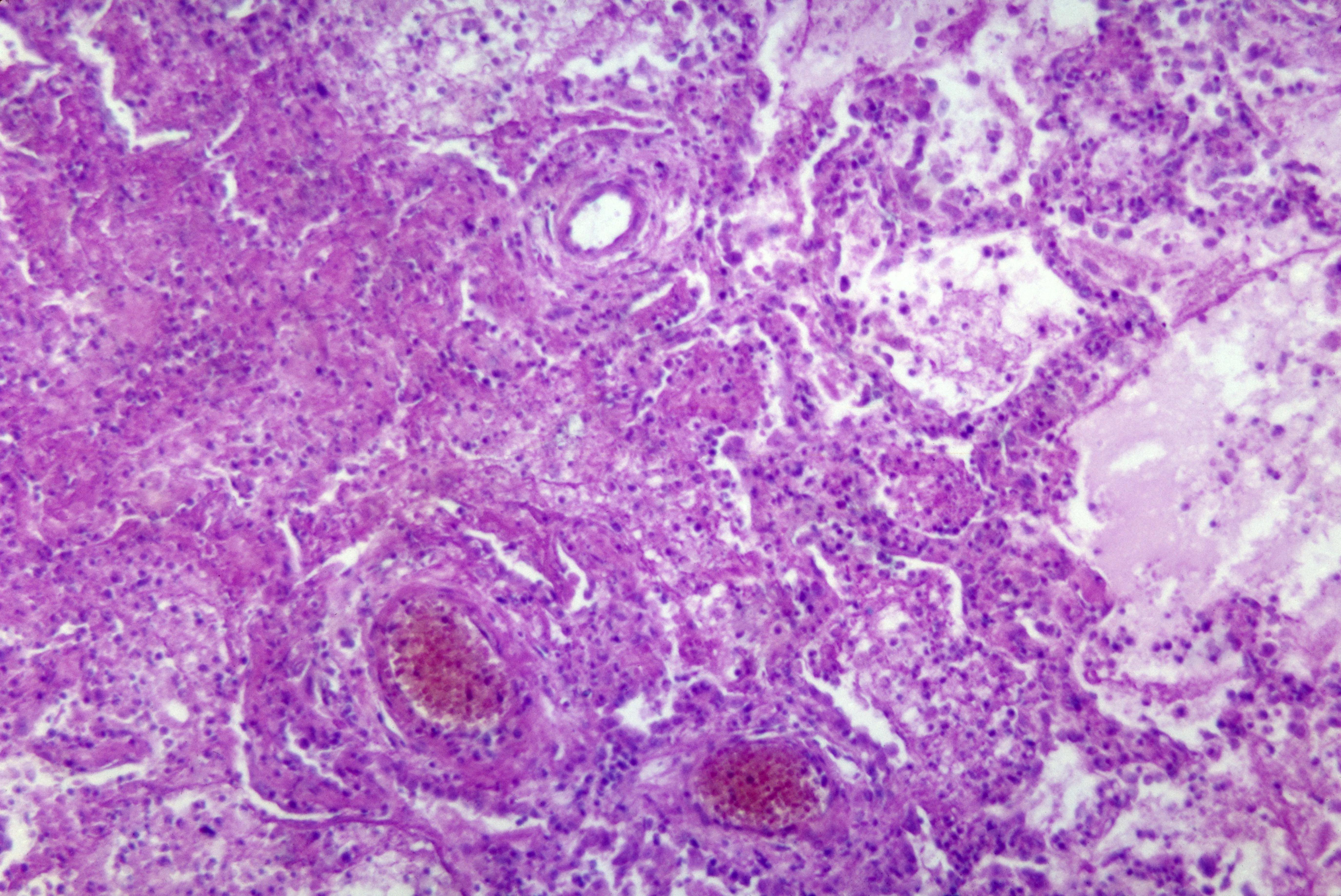

But Toxoplasma infections can cause long-term epigenetic changes in a range of cells around our body.

Our collaborative team – bringing together expertise in Toxoplasma, epigenetics and behavioural neuroscience – decided to investigate whether epigenetic changes caused by Toxoplasma infection in mice could be passed between generations.

To narrow our investigations down to the transmission of epigenetic information through gametes, we decided to study male mice which had been infected with Toxoplasma. The only influence these fathers could have on their offspring was contained within their sperm cells.

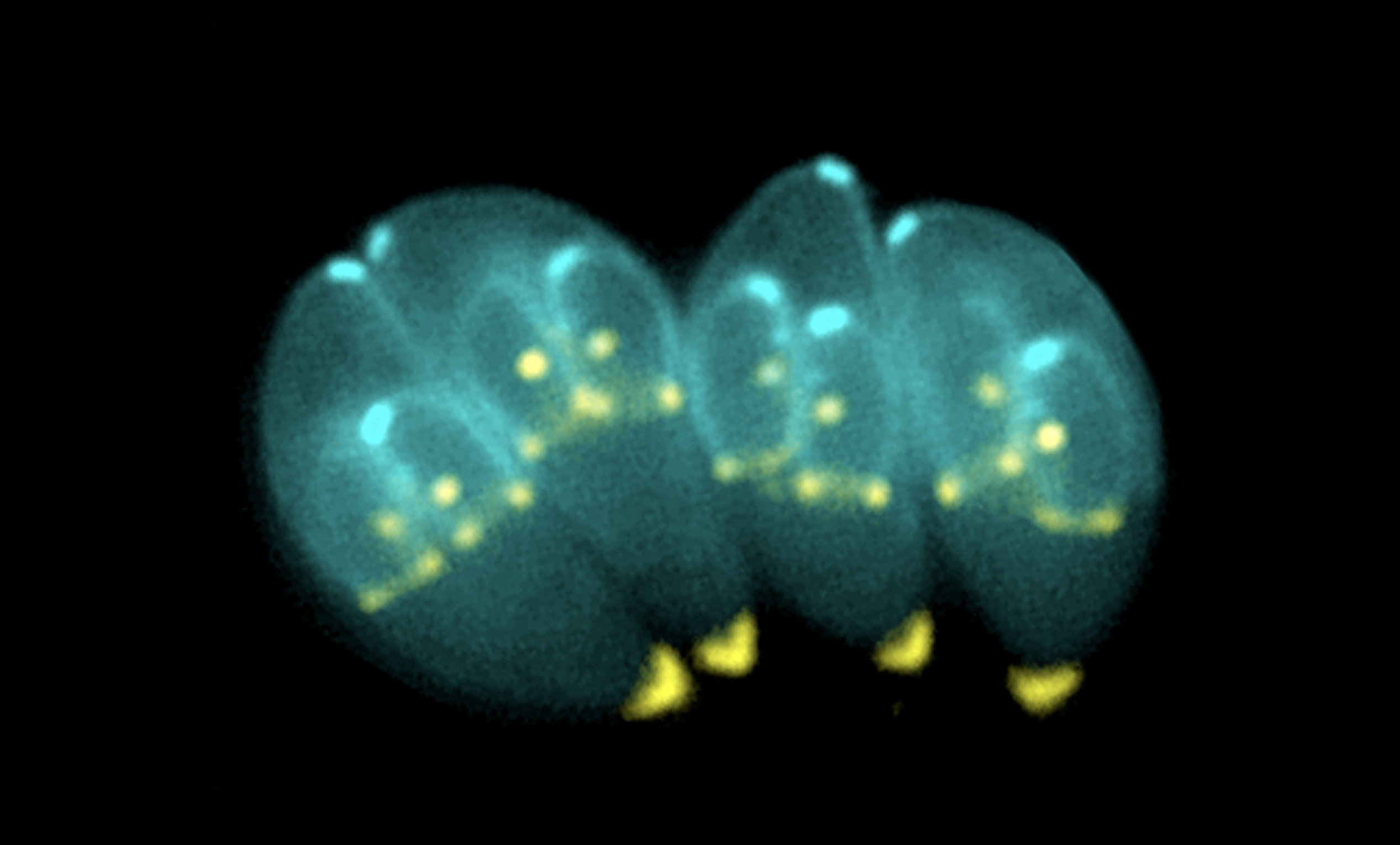

We discovered that Toxoplasma infection alters levels of DNA-like molecules, called ‘small RNA’, that are carried by sperm, as well as the paternal DNA that will be inherited by the offspring.

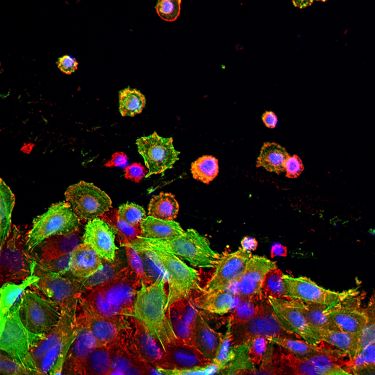

These changes in small RNA levels affect gene expression, and so could potentially influence brain development and behaviour of offspring, which we indeed found.

We also found that the effects of infection on the first generation were different for male and female offspring, an important observation in terms of disease susceptibility and outcome. Even the next generation – the ‘grandchildren’ of the original infected males – displayed changes in their behaviour.

Our discovery is the first to show that an infection in a male can result in epigenetic changes being transmitted to subsequent generations.

Health & Medicine

Decoding cancer cell communication

While our studies were in mice, they have raised an important question about whether infections in human fathers before conception also impact their children.

Currently, we normally focus on how infectious diseases in women affect the developing foetus, but perhaps certain infections in men could have long-term impacts on subsequent generations’ health?

Our body’s inflammatory response to infection can also induce epigenetic changes in cells and so it is critical to continue pinpointing the biological mechanisms behind our observations.

This is something we are following up, both looking at what is happening in humans, as well as investigating infections other than Toxoplasma, including animal models of the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes COVID-19.

How infectious ‘experiences’ can be passed down through generations has enormous public health consequences. It is a paradigm shift in understanding the effects of environment on brain function and dysfunction, and how major neurological and psychiatric disorders might develop.

If pathogenic infections can affect the next generation, this could have enormous impacts on human health.

We need to understand the extent to which such ‘transgenerational epigenetic inheritance’ occurs in humans and how we might prevent transmission between generations.

Continuing research can better inform clinical practices regarding our health before conception, optimising the health of babies and children.

The research was supported by the David Winston Turner Endowment, the DHB Foundation (Equity Trustees), the National Health and Medical Research Counciland the Victorian Government.

Banner: Shutterstock