Business & Economics

Treating depression to economically empower mothers

Despite reports of the demise of psychoanalysis, in some parts of the world, Freud’s psychoanalytic ideas are alive and well

Published 1 July 2019

Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx were the towering figures of twentieth century thought and Marxist ideas have had a resurgence in recent years; ostensibly underpinning the world’s most populous nation - China.

On the other hand, the death of Freud’s psychoanalysis has been proclaimed on many occasions and, increasingly, it is seen as a relic from a bygone era of topcoats and lace.

But University of Melbourne research suggests that reports of the death of psychoanalysis are exaggerated and that, in some parts of the world, Freud’s psychoanalytic ideas are alive and well.

For decades, critics of psychoanalysis have assailed its questionable scientific foundations, its suspect views on gender and the flaws in its founder’s character.

Business & Economics

Treating depression to economically empower mothers

A few generations ago, the mental health disciplines rested on a psychoanalytic foundation.

Today, they have largely abandoned psychoanalysis in favour of psychiatric medications, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and short-term, couch-free forms of therapy.

But psychoanalytic ideas remain influential in some corners of the humanities, some psychoanalytic institutes continue to train candidates and there are researchers attempting to marry psychoanalysis and neuroscience.

Psychoanalytic concepts have also found their way into mainstream psychology and psychiatry by a process of assimilation, losing their Freudian accents and becoming more commonplace.

Psychoanalytic ideas may or may not have lasting value in the academy and the clinic, but do they still have currency in our culture? Do people still understand themselves, others and mental illness through a psychoanalytic lens? Or have we moved on to instead embrace brain science, well-being and personal branding?

At the University of Melbourne, we have attempted to answer this neglected question by tracking the frequency with which a large set of psychoanalytic concepts are mentioned in almost five million English-language books.

Those books were published between 1900 — when Freud’s pioneering work started to appear in print — and 2008.

We also tracked the frequency of these concepts from 2008 to 2017 in a massive body of American English language materials drawn from popular magazines, fiction, academic journals, newspapers and spoken language.

Health & Medicine

What is mindfulness? Nobody really knows, and that’s a problem

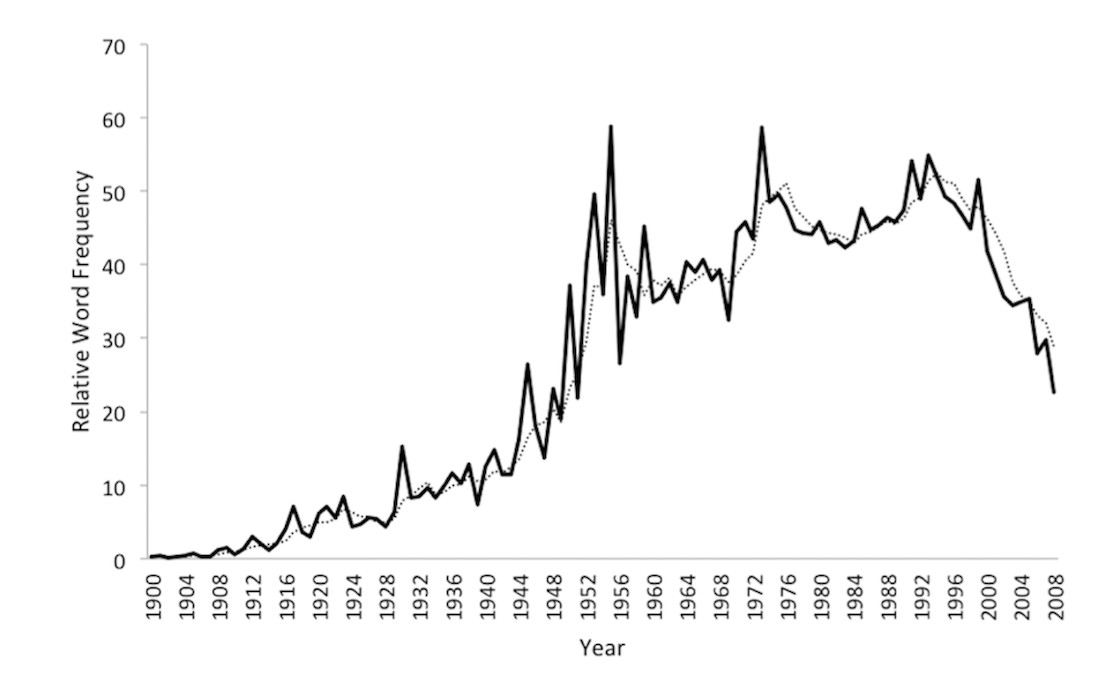

In Figure 1, we see the average trajectory of 55 psychoanalytic terms including ‘defence mechanism’, ‘Oedipal’, and ‘psychoanalysis’ from 1900 to 2008. The vertical axis represents the frequency of these terms relative to all other terms in the vast body of books.

The graph illustrates that psychoanalytic concepts gradually grow in prominence in the first four decades of the twentieth century. They then rise explosively in the 1950s and 1960s, lurch slightly upward until the 1990s and then fall off a cliff.

In 2008, they are mentioned 55 per cent less frequently than their mid-1990s peak. Our analysis of American text found a continuing annual decline of about four per cent during the following decade.

So, it might seem that psychoanalysis’s cultural impact is in free-fall. But not so fast.

The rise and decline we observed in English-language books may not hold in other settings.

To this test possibility, we replicated our analysis using French-language books.

Freud’s work was slow to be translated and popularised in France but from the 1960s, according to one historian, “the French attitude toward psychoanalysis swung from denigration and resistance to infatuation”.

Psychoanalytic thought also plays a much larger role in the mental health field in France than it does in the Anglosphere.

Business & Economics

The grim cycle of homelessness and unemployment

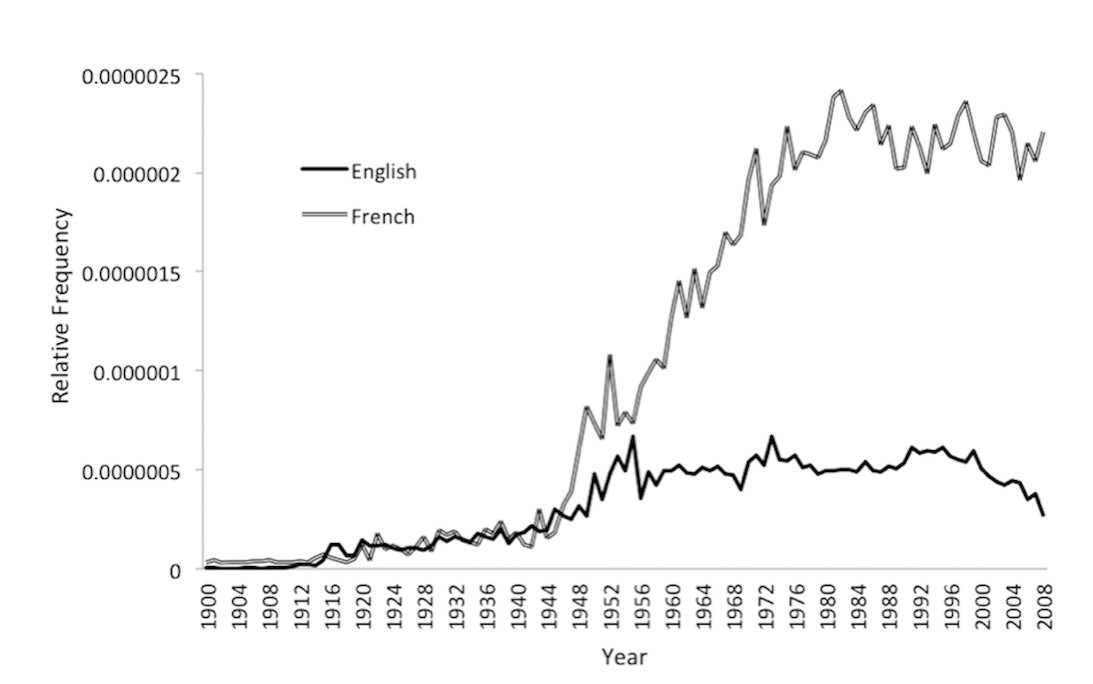

So, does the cultural prominence of psychoanalytic ideas show the same steep rise and even steeper fall in French-language books as it does in English? We find that it doesn’t.

The same set of psychoanalytic terms, now in French translation, rise in relative frequency at a slower pace than they did in English but accelerate upward in the 1960s, and remain at much the same level of prominence from the 1970s to the 2000s – with no Freudian slip.

But the average relative frequency of the set of psychoanalytic terms only tells half the story. So next we plotted the summed or total relative frequency of the terms in both languages.

Figure 2 reveals that since the 1960s, psychoanalytic concepts appear at a much higher rate in French-language books, indicating that psychoanalysis is vastly more culturally prominent in contemporary France than in the Anglophone world.

Our findings suggest that a simple rise-and-fall narrative does not capture the cultural reception of psychoanalysis on a global scale.

While psychoanalytic concepts appear to be in retreat outside the academy in the Anglosphere, our results suggest they continue to thrive in France.

This discrepancy may have upsides and downsides.

Arts & Culture

Museums: They’re good for your health

The continuing prominence of psychoanalysis in France has been linked to the persistence of troubling approaches to the treatment of autism, but it may also contribute to the high public accessibility of psychotherapy.

The decline of psychoanalysis in the English-speaking world may represent a beneficial rejection of pseudoscience and mother-blaming, but perhaps also indicates a waning recognition of the depth and complexity of the human psyche.

Our research shows that psychoanalytic ideas are very much alive, but in an increasingly restricted range of intellectual and cultural habitats.

Upon Sigmund Freud’s death in 1939, the great American poet W. H. Auden wrote that he was “no more a person now but a whole climate of opinion.”

In the Anglosphere, that climate warmed until the 1990s and is now cooling rapidly.

That the climate is still rather tropical in the French-speaking world is a testament to the unevenness of cultural climate change.

Banner: Getty Images