Business & Economics

Australia’s Banking Royal Commission: Quo vadis?

There is an important but poorly understood relationship between New Zealand’s banks and the Australian taxpayer that highlights the need for more stringent regulation around the Big 4’s ‘too big to fail’ guarantee

Published 28 January 2019

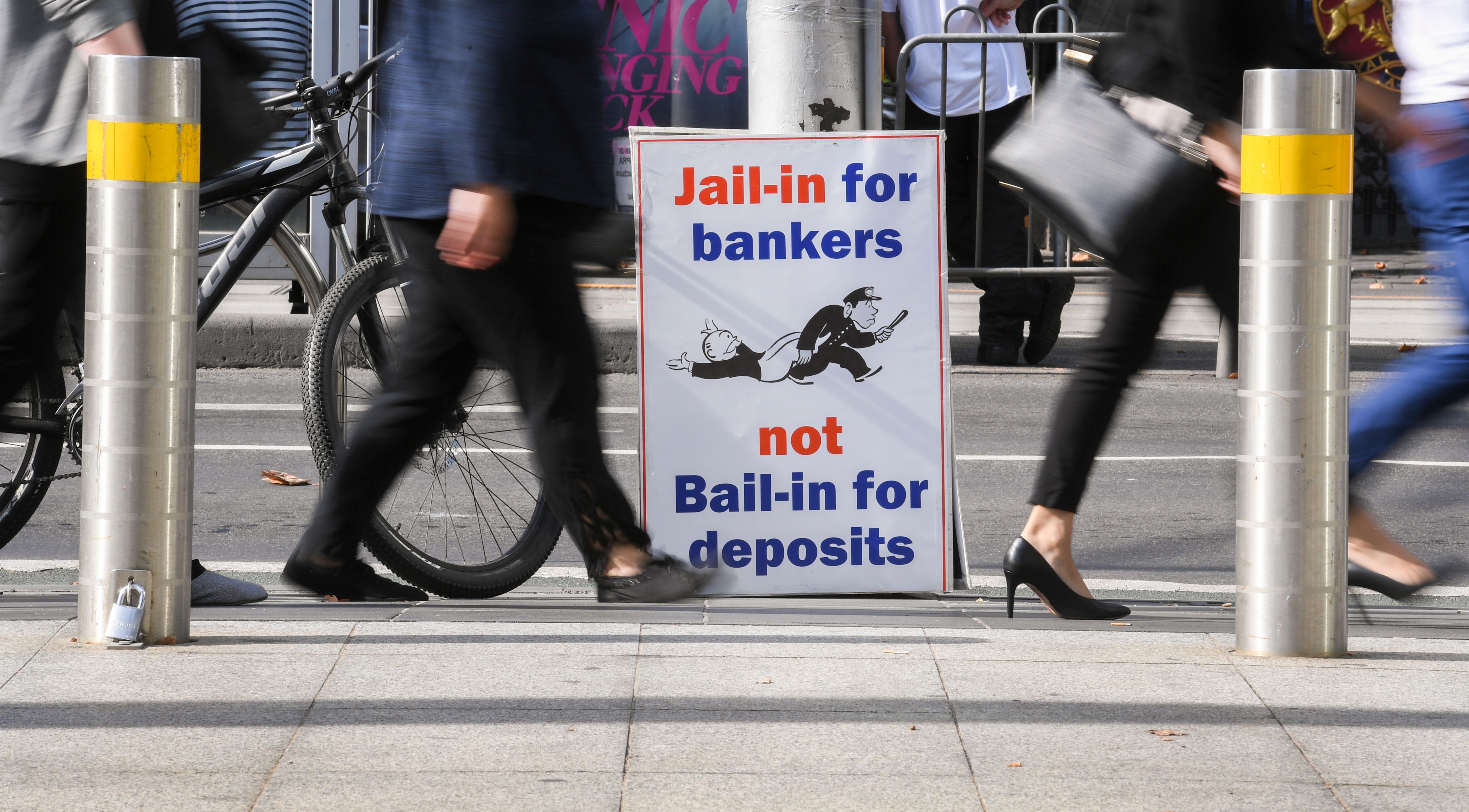

Australian banks have come under increasing scrutiny in light of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

More attention than ever is now on the operating practices of our Big Four banks – the National Australia Bank, the Commonwealth Bank, ANZ and Westpac – and the ways in which their operations affect the lives of everyday Australians.

However, there is something that is continually overlooked when we talk about Australian banks – their subsidiaries in New Zealand.

Many major banks in New Zealand are actually fully-owned by Australian parent banks.

This has important practical implications, a fact acknowledged by the Financial Markets Authority NZ and Reserve Bank of New Zealand when they completed their own review into the conduct and culture of New Zealand’s banks in November last year.

Business & Economics

Australia’s Banking Royal Commission: Quo vadis?

Banks are exposed to the risks posed by one-another. The failure of one bank may impose losses on other banks, causing a domino effect. The risk that a bank failure will trigger a cascade of further failures is particularly severe if the bank in question is large and systemically important.

For this reason, if a systemically important bank gets into difficulties, the government of the country in which it is domiciled will typically intervene with a rescue package before it fails.

Government intervention in the banking sector comes in several forms. One form is deposit insurance. This is a formal guarantee that protects the savings of households, up to a certain limit, in the event of a bank failure. This kind of insurance is generally limited to household deposits.

Another form of intervention is an emergency loan, or ‘bailout’. Bailouts are intended to directly support troubled banks and prevent their failure. This prevents people from losing their savings but it also benefits investors.

Because governments have incentives to offer bailouts in troubled times, systemically important banks enjoy a ‘too big to fail’ (TBTF) guarantee. Access to bailout funds isn’t enshrined in law, however. For example, Lehman Brothers, the US’s fourth-largest investment bank at the time, was allowed to fail in 2008. Nonetheless, there’s a widespread expectation among investors, based on prior experience, that governments will generally not let big banks fail.

Politics & Society

Misleading conduct? So what!

This is valuable for big banks. If investors expect government bailouts in the event of a crisis, they will be willing to lend to big banks more cheaply than to smaller institutions that don’t benefit from the TBTF guarantee.

One way to measure the degree to which the TBTF guarantee benefits a bank is to calculate the difference between the fair price of insuring against its failure and the actual market price of that insurance.

Typically, the market price of the insurance is lower than its fair price. The difference between the two is due to the expectation that the government will rescue the bank if it gets into trouble. And because the TBTF guarantee is costless to the banks, it amounts to a government subsidy.

The result is an imbalance.

In good times, systemically important banks profit from low borrowing costs due to the TBTF guarantee. In bad times, they don’t face the full cost of their failure. Rather, the cost is borne by the taxpayer.

This then leaves banks with weakened incentives to act prudently to prevent excessive risk-taking.

New Zealand is trying to rectify this imbalance.

Business & Economics

Making the financial industry more like a health service

Simply put, if a New Zealand bank fails, the government has declared that it won’t provide emergency funds and that it will allow the bank to go under. And there’s more – households that have their money with the failed bank risk losing some of their savings.

The reason for this policy is that the government wants banks to take steps to prevent their own failure.

Suppose that a financial crisis hits both Australia and New Zealand at the same time – a plausible scenario given that both economies are exposed to similar risks. In this case, a New Zealand bank might fail just as the Australian banks are also coming under stress.

Now, if the New Zealand subsidiary of an Australian bank were to fail, then instead of a bailout from the New Zealand government, there could be a bailout from the Australian parent bank.

What if this puts the parent bank into jeopardy?

The Australian taxpayer may then have to bail out the Australian parent bank. In that case, Australian taxpayers are essentially supporting the New Zealand banking system.

There are several possible solutions to this potentially problematic relationship.

One is that New Zealand could legislate deposit insurance and rescind the declaration that banks will be allowed to fail. In this scenario, New Zealand’s taxpayers would be responsible for bailing out New Zealand’s banks.

Business & Economics

When families and money don’t mix

But from New Zealand’s perspective, this is unfair. Australian owners collect the profits in good times, while New Zealand’s taxpayers foot the bill in bad times. It also places the burden on regulators to prevent banks from taking excessive risks.

Alternatively, Australia could follow New Zealand’s lead and think carefully about the cost of letting its own banks act like they are too big to fail. But the question is whether there’s the political and regulatory will to do this.

Another intriguing possibility is to formalise the TBTF guarantee and have it codified in law. This would mean that the government could charge systemically important banks for the insurance that they receive.

In light of the Royal Commission’s scrutiny of the banking sector, now might be an opportune moment to develop more stringent regulation and to remove some of the taxpayer subsidisation of Australia’s large banks.

A version of this article also appears on The Conversation.

Banner image: Shutterstock