Business & Economics

Home ownership remains a pipe dream for many Australians

Even though stamp duty is highly inefficient, replacing it with an alternative tax will always be controversial – but what are the options?

Published 11 February 2021

Australia avoided a recession during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) due to a mixture of good luck and good policy.

Our proximity to Asia helped to moderate the economic downturn, while economic reforms implemented over the last few decades acted as a shock absorber to reduce their impact upon Australia.

Now in the midst of another global recession, even if the Australian government successfully navigates the COVID-19 pandemic, a serious challenge remains for the economy.

Since the GFC, productivity gains in advanced economies have slowed. And these productivity gains lay the foundation of future growth in living standards.

With productivity growth expected to remain muted, it becomes increasingly important for policymakers to strive for reforms to economic institutions. And the tax system should be top of the list.

Business & Economics

Home ownership remains a pipe dream for many Australians

It is commonly agreed that property transaction taxes are highly inefficient – this was outlined in The Henry Review, which was commissioned by the government in 2008 and intended to guide Australia’s tax system reforms over the next 10 to 20 years.

Property transaction taxes are an important source of state government revenue that are incurred when a house is sold – more commonly known as stamp duty.

Our research examines the cost and benefit of replacing stamp duty with either a recurrent property tax based on the value of the home or with an increase in consumption tax.

We’ve then analysed how Australians could be affected by these reforms.

Stamp duty reduces transactions in the housing market and prevents mutually beneficial gains.

Taxes like this also present a barrier for homeowners wanting to move when a residence no longer suits their needs – like when a family outgrows their first family home.

Then there’s mobility. Reduced mobility can have ramifications beyond the housing market. For example, it may be difficult for people to accept better jobs that are located too far from their current residence.

Business & Economics

The impact of COVID-19 on Australia’s housing market

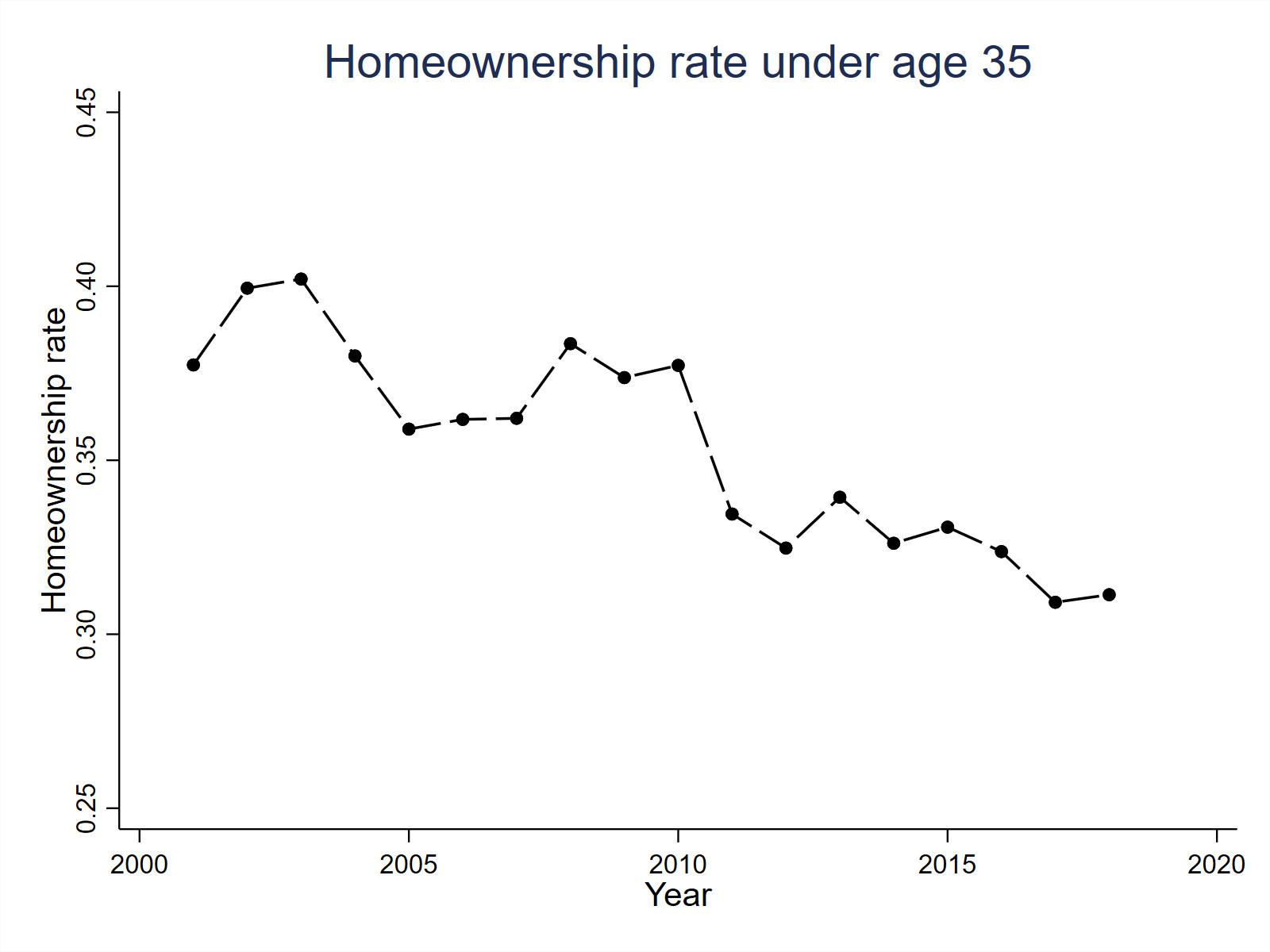

Stamp duty also increases the down payment required to purchase a home, making it more difficult for young households to enter the property market. (Figure 1).

Over time, as house prices have increased the burden of stamp duty has become larger, and these problems have become more severe.

Finally, stamp duty is one of the most volatile taxes, as the revenue raised varies based on movements in the property market.

So, if the goal for state governments is to deliver a stable revenue stream then stamp duty is not fit for modern purpose.

So, why do we still have stamp duty? The challenge of removing stamp duty is finding a viable alternative.

Although stamp duty is inefficient, removing it would realistically require either a reduction in government services or an increase in government revenue. So, state governments would eventually have to increase taxation from other sources or reduce their expenditure.

Australia already has low tax rates compared to many countries within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), so presumably other sources of government revenue would have to be raised.

And here is the challenge for governments: even though stamp duty is highly inefficient, replacing stamp duty with an alternative tax will always be controversial as it will raise the tax burden on some people and lower it for others.

Business & Economics

Too many eggs in the property wealth basket

Our model shows that removing stamp duty would reduce the purchase price for home buyers, increase the sale price for sellers, increase the total number of transactions and reduce the degree of mismatch in the housing market.

We’ve also found find that the rate of home ownership would increase – particularly among younger segments of the population who currently have difficulty in saving for an initial house deposit. Our model predicts reforming the tax system could increase the homeownership rate among individuals under the age of 35 by three to four percentage points.

There would also be an increase in the rate of current homeowners moving to new homes which allows a more efficient allocation of housing as people are more willing to move in response to their changing circumstances.

Our economic model also allows us to address welfare issues.

First, in our model economy we find people entering the economy prefer a tax system with stamp duty or a system with a property tax, or a system with increased consumption taxes. Here, our answer is unequivocal.

Young adults entering the economy, would typically prefer a system with a recurrent property tax rather than a consumption tax or stamp duty

Current homeowners would typically benefit from replacing stamp duty with consumption taxes rather than property taxes.

Health & Medicine

Australian homes on the line

Why is this so? Well, over 65 percent of households in the Australian economy own property outright or are in the process of paying off a mortgage. For these households, moving to a property tax – which increases their tax burden – is less attractive than moving to a consumption tax.

Our economic model also suggests that the welfare effects will vary by demographic characteristics, income, and home ownership.

Renters typically benefit more from the removal of stamp duty than homeowners. Houses become easier to purchase and this benefits groups that are currently excluded from homeownership by the greatest amount.

Perhaps surprisingly, we also found that older landlords will also tend to gain from the removal of stamp duty. They do so because this will in many cases increase the value of their housing portfolio, outweighing any cost associated with an increased tax burden.

This raises a challenge for governments.

In the long run, our research shows that a land or property tax is preferential to the current status quo. But it will be difficult to get broad-based support for the removal of stamp duty and its replacement with a property tax from current voters.

Some state and territory governments have already taken steps to eliminate stamp duty.

In the Australian Capital Territory, there’s a 20-year plan for the transition from stamp duty to land taxes (which are similar in many ways to a property tax). This involves the gradual elimination of stamp duty and the gradual increase of land taxes.

The New South Wales’ government has an alternative proposal. Households purchasing property in the future may be allowed to select either a recurring land tax or a one-off stamp duty levy. These are good policies that should increase the efficiency of the tax system and benefit future generations.

The gradual transition – either by increasing the length of the policy change or by allowing households to select into different tax payment systems – helps make these policies more palatable to the voting public and also provides a pathway for other state governments to follow.

The sooner, the better.

Banner: Getty Images