Politics & Society

Russia’s meddling in the French elections: How and why?

Europe’s social democratic parties are failing to articulate a vision for the future, fuelling the rise of the populist Right

Published 30 March 2017

As right-wing populism continues to rise in some European countries, support for social democratic parties has been in retreat in recent years.

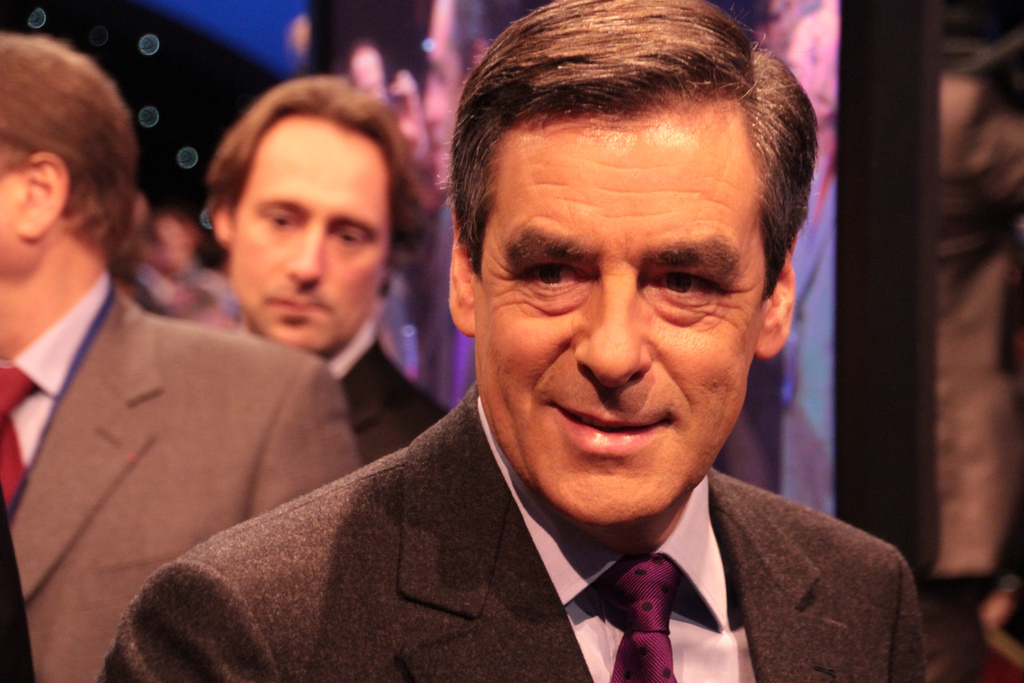

Support for France’s two Left-wing candidates Jean-Luc Melanchon and Benoit Hammon in the upcoming Presidential election is trailing National Front candidate Marie Le Pen, Right-wing candidate Francois Fillon and centrist Emanuel Macron.

In the Netherlands, the dramatic loss of seats held by the Labour (PVDA) Party from 38 to 9 in the recent elections suggests that social democrats are in crisis there too.

The Dutch Labour Party lost legitimacy by being part of a coalition led by the centre-Right Liberal (VVD) Party which adopted austerity policies. The Liberal Prime Minister Mark Rutte cut social spending, raised the retirement age and abandoned the commitment to aid of 0.7 per cent of GNI.

Many voters accused the government of neglecting the elderly and making health care unaffordable. That is, Dutch Labour appeared to have abandoned the goals and policies for which it had once stood.

Politics & Society

Russia’s meddling in the French elections: How and why?

Since the collapse of international financial markets in 2008, unemployment, especially among the young, is high, inequality is growing and disillusionment with the European Union and its monetary institutions has intensified.

The dominant influence for identifying means of economic recovery has been neo-liberal ideology – deregulation, fiscal contraction, privatisation. These were the nostrums imposed on Greece when it wrestled with national bankruptcy, even though many recognised that such policies would further reduce its capacity to repay debt.

Many governments reluctantly adopted such restrictive strategies because the financial markets and their institutional advocates, such as the IMF, urged them to do so. Many of the social democratic parties thought they had no alternative to absorbing this avalanche of opinion. So they ceased to be lighthouses of alternatives, as they had been in the decades immediately after the Second World War.

Political debate has become dominated by the subtleties of technical macroeconomic policy rather than discussion of how to achieve the equitable, inclusive, secure, sustainable societies which social democratic parties had once aimed to build.

In the absence of that identifiable vision and the practical policies to implement it, the social democratic parties lost their appeal.

A similar situation developed in Australia when the Labor Party mistakenly adopted the contractionary policies of the ‘recession we had to have’; unemployment multiplied and the Party lost its humanitarian and ethical way. Rudd appeared to offer an alternative and handled the global financial crisis well, but the change of direction lacked depth until the formulation of the concrete alternative policies with which it campaigned during the 2016 election.

Politics & Society

Dutch election results are the opposite of Trump-like populism

In many countries now, the lack of a clearly articulated social democratic vision and strategy is a major reason for the growth in attractiveness and support for the populist parties of the Right. Leading political scientist Professor Sheri Berman writes that there is a ‘causal connection between the failures or missteps of the centre or social democratic left and the rise of right-wing populism’.

In the forties, fifties and sixties social democratic parties offered attractive solutions to rebuilding Europe. Their policies were neither intended to displace the market nor to give it free reign. They sought to enable market dynamism to stimulate economic growth, but also to do so in ways which aimed for equitable distribution of the benefits. They aimed for employment, education, health, inclusiveness and cultural vitality for all.

Social democratic parties everywhere will be in terminal decline unless they can revitalise their vision and strategies. This involves analysing the present malaise and identifying practical, sustainable and effective means of tackling them.

This involves, for example, aiming for the interlocking goals of work for all who want it, high quality care in early childhood and after retirement, accessible education and health services, imaginative programs for providing affordable housing, strong and comprehensive renewable energy programs and major expansion of research capacity.

Peace can be actively sought by establishing conflict resolution bureaus to attempt mediation rather than military intervention whenever violence is threatened, negotiation of a nuclear disarmament treaty and negotiating reductions in expenditure on conventional weapons.

Some powerful corporate interests will say this sounds like idealistic fantasy. But a major lesson from recent election outcomes is that voters want hope.

Electorates are now sufficiently disenchanted with conventional policies and the wrangling style of politics that they will vote for what is perceived to be different. So fresh vision can be realistic if it is linked with programs for implementation which make sense and are articulated by persuasive leaders.

It is striking to observe the renewed support for Germany’s Social Democrats, from 20 per cent to 31 per cent, following the selection of Martin Schulz as their candidate for Chancellor. This put him only three percentage points behind Angela Merkel – who in any case by Australian political standards, is a pragmatic social democrat. The German election could therefore be substantially different from that in the Netherlands.

This article was co-published with Election Watch.

John Langmore is a professorial fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne. He was a federal Australian Labor MP from 1984 until 1996.

Banner image: Garon S / Flickr