Arts & Culture

A blow to the heart of the City of Light

As we head into the Paris Olympics, has the dream been compromised, even ruined, by other upheavals in France’s fevered summer?

Published 15 July 2024

July is usually a sweet month for French people as they enjoy the spectacle of the Tour de France weaving its way through the visual delights of the countryside, punctuated by the annual festivities for Bastille Day. Annual holidays in August loom for most.

July 2024 was to be uniquely special, with Notre-Dame cathedral restored to its former glories after the 2019 fire as if in a blessing for the Paris Olympics opening on the 24th.

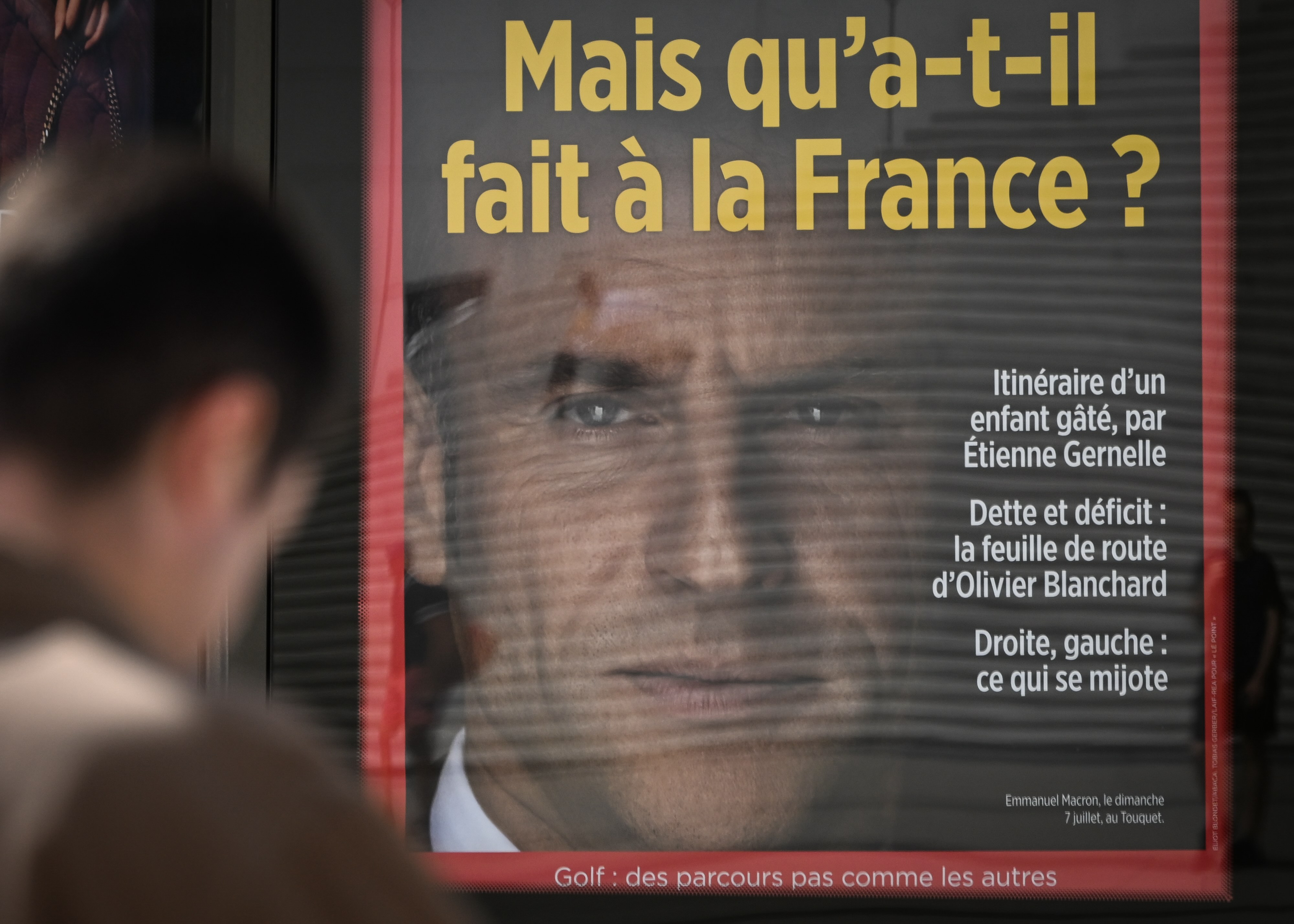

This would be the pinnacle of Emmanuel Macron’s second presidency.

It hasn’t turned out that way. The mounting excitement and apprehension at the approaching opening ceremony of the Olympic Games is coinciding with acute political and social tensions.

Will this be a summer to remember for the wrong reasons?

In May, mounting discontent at the policies of the Macron government, led by France’s youngest post-war prime minister Gabriel Attal, erupted in New Caledonia.

Arts & Culture

A blow to the heart of the City of Light

Changes to local electoral laws, perceived to favour French expatriates, sparked weeks of rioting in May and June. Although the proposed laws have been “suspended”, the territory is effectively still in lockdown and devoid of tourists – a key source of its income.

Then, in the European elections on 9 June, many French voters aimed their resentments at the Macron government. In 2019, the far-right National Rally (NR) party of Marine Le Pen had garnered 23 per cent of the vote; this year its 31 per cent was more than twice that of President Macron’s Ensemble (Together) coalition.

In recent years, Le Pen has successfully sought to distance herself from some of the more extreme views on race and history associated with her father Jean-Marie, founder of the former National Front.

Her trenchant opposition to immigration, particularly from North Africa, and economic nationalism have appealed to voters struggling with the cost of living and precarious employment at a time when Macron is identified by many as a ‘president for the rich’.

Despite some economic successes – the lowest unemployment rate (seven per cent) since 1982, and inflation at 2.6 per cent – Macron’s positive international image as an eloquent defender of European liberal values is not reflected in popularity inside France.

Macron’s decision to call snap national legislative elections in response to the right-wing challenge seemed to have backfired spectacularly when, in the first round on 30 June, the NR won 34 per cent to Ensemble’s 21 per cent.

A rapidly formed left-wing New Popular Front (NFP) alliance won 29 per cent.

Politics & Society

Echoes of revolution

But in 93 per cent of electorates, the NR was the highest polling party. For the first time since World War II a far-right party was on the brink of winning national power in the second, final round on 7 July.

The wildly popular captain of France's football team, then competing in the 2024 Euro championships, Kylian Mbappé, reacted to the first-round results by warning:

“We can't leave our country in the hands of those people there. I think we all saw the results, it's catastrophic. We hope that that will change and that everyone will mobilise to vote, and to vote for the right side.”

Mbappé had expressed a view that most came to agree with.

The second round of voting, where any first-round candidate with at least 12.5 per cent of eligible voters could stand, saw a dramatic realignment across the rest of the political spectrum as most centre and left parties reached agreement about supporting a single unity candidate against the NR.

The results were unanticipated and dramatic.

Whereas the NR had anticipated winning as many as 300 of the 577 seats, a clear majority, in the end it picked up only 143.

The newly formed NFP were the great victors, with 182 seats, while Macron’s own party tumbled from 245 to 168 seats, still far better than predicted.

Politics & Society

The symbolism of the Olympic Games

Macron’s big gamble succeeded, but at the cost of many from his own party.

A large majority of French people have repudiated a far-right solution to their nation’s challenges, and the results will reassure France’s international allies (in particular, Ukraine).

But the fact remains that the single most popular political party, with about 30 per cent support, is the NR that advocates a range of exclusionary policies towards immigrants and refugees, and questions France’s commitment to European and international alliances.

Macron’s centrism is dead; his Ensemble party is a minority. His great challenge now is to find a prime minister and cabinet that can somehow form and hold together a parliamentary majority which ranges from traditional conservatives to the various socialist parties.

All they have in common is opposition to the NR. Macron has excluded any alliance with the hard left of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Unbowed.

Now attention turns to the Olympics.

Vast sums have been spent in seeking to make the River Seine both the centrepiece of the opening and clean enough for swimming. Will that be achieved?

The games have been touted as the greenest games in Olympics history, as would befit the home of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The athletes’ village has a geothermal cooling system that pumps cold water from below ground to maintain indoor temperatures at least 6°C cooler than the outside, but some national teams have been busy ordering air-conditioning units to further cool the often-stifling August air in Paris.

Politics & Society

Why France?

Emmanuel Macron had hoped that the Cathedral of Notre-Dame would be restored and reopened for the Olympics. It is almost ready, but visitors to the games will at least be able to marvel at the speed and quality of the restoration.

Qualifying that delight will be the unsettling question of whether the joy of being in the City of Light will be compromised, even ruined, by other unanticipated upheavals in France’s fevered summer.

The Olympics spectacle will at least give Macron the space to seek to stitch together a government with which he can work across the final years of his presidency.