It’s time to build South Asia literacy in Australia

Universities are key to boosting a new generation of South Asia literate Australian graduates as the world’s centre of gravity moves East

Published 20 February 2023

The relationship between Australia and India is booming.

A major new trade deal has been agreed and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will be in India next month. In return, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi is due to come to Australia later this year.

This boom is a good moment to reflect on the nature of Australia’s relationship with India and other South Asian countries as well as explore some of the opportunities these relationships provide.

In his comprehensive report on boosting Australia-India ties, former Australian High Commissioner to India and Chair of the Asialink Council, Peter Varghese, wrote of the various potential ways that Australia and India could work more closely together.

This ranged from education, defence, and health to technology, cyber-security, and investment.

Varghese also made the important point that the Indian diaspora in Australia has grown enormously throughout the twenty-first century. Australia is increasingly Indian.

But Varghese added a rider: A notable obstacle to developing the Australia-India relationship is the rather low ‘India literacy’ within Australia.

Many India or South Asia undergraduate and graduate programs closed in Australia in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

In the mid-1990s, there were 13 South Asia or India programs running in Australia. But by 2022, that number had dwindled to two: a program at the Australian National University and one at the University of Sydney.

And this decline reflects the broader trend downward of Asia Studies in Australia.

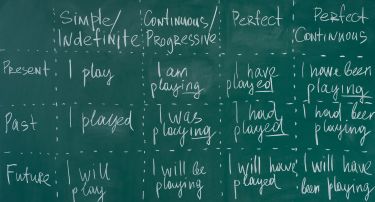

Language teaching has virtually disappeared.

Six Australian universities taught Indian languages in the mid-1990s, now only three do so. And no languages, other than Sanskrit and Hindi, are taught in Australian higher educational institutions.

Hindi is one of the fastest growing languages in Australia. But the number of fluent Hindi speakers of non-South Asian origin in Australia could be counted on the fingers of two hands.

Universities do a great deal to bridge the gap between Australia and India, for example through research collaboration – but the task of building knowledge of India and South Asia has fallen behind.

There are signs of change.

Bucking the trend is the Faculty of Arts and Faculty of Science at the University of Melbourne which have teamed up to develop a new Minor in South Asian Studies, hosted by the Asia Institute. This new Minor allows students to develop a specialist knowledge of South Asian countries including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bhutan.

The Minor is taught by an interdisciplinary team of scholars working in fields as diverse as public health, anthropology, philosophy and political science.

There’s a lot more that needs to be done, however, and not just because of the increasingly friendly relations between Australia and India.

The centre of gravity of the world is moving East.

India and its neighbouring countries have young demographic profiles – around 60 per cent of India’s population is under 30, and India will overtake China as the most populous country in the world this year.

South Asian countries will be increasingly crucial to the world’s economy.

South Asia – a fifth of humanity – contains a massively vibrant set of religious, cultural, artistic, ethical and social practices. It is a region, too, of course, in which some of the most pressing challenges of the mid-21st century will converge.

South Asia is at the epicentre of linked crises related to climate change, social inequality, and the absence of effective primary health care in many parts of the region.

In addition, the jobs of young people who emerge with university degrees in Australia are increasingly likely to be linked to South Asia.

An economist, political scientist or public health graduate who can also say that they have a broad understanding of South Asia’s economy, politics, society, cultural practices and language is likely to have an advantage in competitive job markets.

In addition to new minors and majors, we need many more opportunities for Australian students to engage with South Asia case material and perspectives in their studies, more opportunities to visit South Asian countries, inventive online offerings in Area Studies, and work-integrated learning that explores how new forms of Area Studies relate to the package of skills required by the modern graduate.

Politics & Society

Becoming Asia-capable

In Japan, colleagues there say that interest in South Asian studies is very robust.

One colleague told us he’s had to set a test for students interested in his subject on contemporary India to manage numbers.

“Young people in Japan know that India is the future”, he said. “And they also want to understand Indian history, language and culture.” The University of Tokyo alone teaches six Indian languages.

Australia could learn from Japan and work to build a new generation of South Asia literate young people with lasting ties to friends across the Indian Ocean.

This is a matter for universities, but also for government which could invest in South Asia learning in Australian higher education, as governments do in the US, Japan, and Canada.

South Asia is the future.

Enrolments are now open for these two new University Breadth subjects that focus on contemporary South Asia in Semester Two, 2023: UNIB10021 Challenges and hopes in contemporary Asia and UNIB 20025: Well Being: Learning from South Asia.

Banner: Getty Images