Health & Medicine

Hearing loss still a challenge for kids

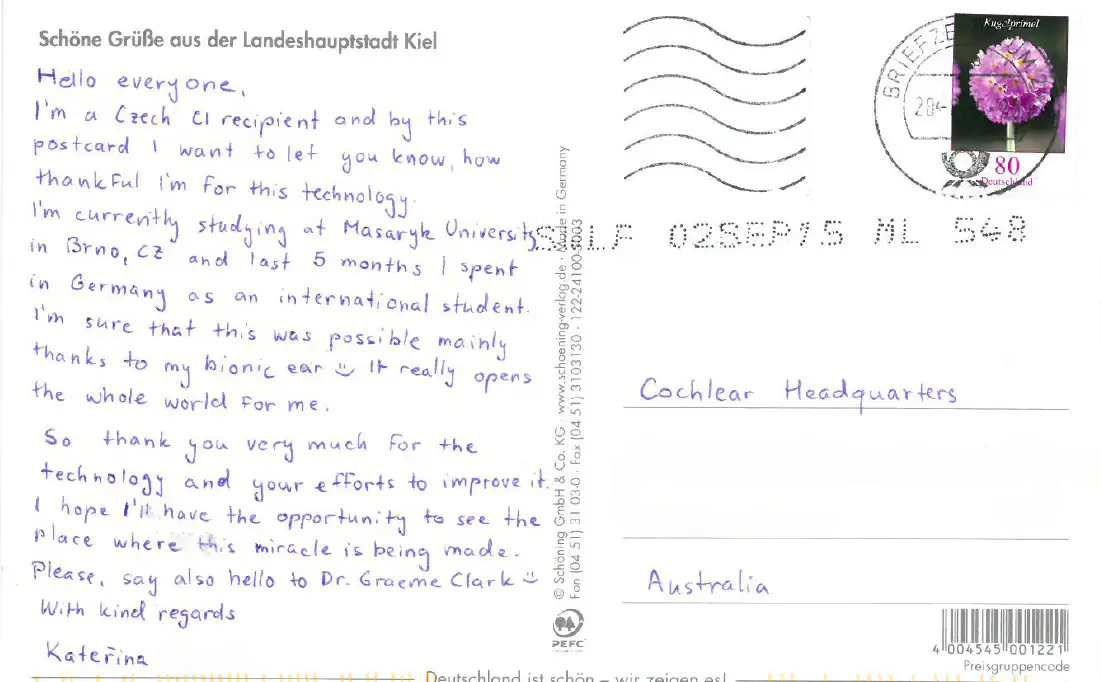

Laureate Professor Graeme Clark AC, who led the team that invented Australia’s multi-channel cochlear implant, says he still cries “tears of joy” when someone’s hearing is restored

Published 25 August 2025

Fifty years ago, Laureate Professor Graeme Clark AC and his team developed a tiny device – the multi-channel cochlear implant – at the University of Melbourne.

The technology brought together medicine, engineering and industry to transform lives. It became a defining moment in Australian biomedical innovation, kick starting an ongoing global transformation in hearing health.

The team performed the world’s first clinically successful multichannel cochlear implant in 1978 – restoring the hearing of an adult.

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the first child to receive a multichannel cochlear implant developed specifically for children, as well as the establishment of the first public hospital Cochlear Implant Clinic, based at The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital.

We sat down to speak with Professor Clark AC about his legacy and how biomedical engineering has transformed global health.

As a five-year-old, I told my kinder teacher, “I want to fix ears because my father is deaf”. At eight, my Methodist minister asked me what I wanted to do, and I said be an eye, ear, nose and throat doctor in Orange in New South Wales – I had a relative on an orchard in Orange.

That surprised him as most boys of my age wanted to be C-class steam train drivers.

At around nine, I read the life of Louis Pasteur by Rene Vallery-Radot and Madame Curie written by her daughter Eve which were on my parents’ bookshelves and was inspired by the beauty and simplicity of their experiments in physics and biology.

Health & Medicine

Hearing loss still a challenge for kids

That really lit a fire in my belly to make discoveries. So, I started with experiments in my mother’s laundry.

At the age of 16, I went into Medicine at the University of Sydney. I did well in physiology and was offered a year off to study sensory brain function. But I postponed the opportunity until after I was trained clinically.

The passion to make discoveries in hearing, brain coding and consciousness has never left me, and I feel it might be like an addiction.

Success for success’s sake was not the focus of my journey.

I wanted primarily to do good science to see if I could discover how to bypass a damaged inner ear and electrically stimulate the brain to reproduce the coding of sound.

At the start of my journey, I was criticised greatly for doing what senior scientists said would not work. I have been surprised that, after years of work, our discoveries have been of great help to deaf adults and children.

I felt like a true scientist – who at the end of his life was delighted to prove himself wrong.

Professionally, I am delighted that the implant gives people what they describe as 'a new life'. Also, when deaf children have an implant at an early age, they can communicate as effectively as a child with normal hearing and develop their true potential in a world of sound.

I still meet children who have benefitted from the cochlear implant and it brings me tears of joy.

Personally, I am most proud of my wife, our five children, their spouses, 12 living grandchildren and (I hope) two great grandchildren. They have such strong family values and a desire to help others.

Early in the 1960s, I was surprised that some Australian doctors seemed to be happy to let researchers from other countries make the discoveries and they would then use the benefits.

I asked myself why we couldn’t do just as well.

At the time, although Australians had invented the stump-jump ploughs, the black box in airplanes, the Hills hoist and other innovations, we were a risk averse country compared to the US – especially when it came to funding research.

But there are now significant advances that make our healthcare system one where ideas can be developed for patient benefit.

I’m still very moved when someone’s hearing is restored, and it is still the same for me as it was years ago.

Seeing children hearing makes it all worthwhile. I still feel thrilled and very emotional. It still makes me almost want to cry like I did when I knew that we had succeeded.

Funding research is still very hard. While some difficulties have abated, others have ignited.

There was once a view that pure and applied research were very different – that applied research was not the domain of a gifted pure scientist.

Louis Pasteur was insightful and said there were only two types of research; good and bad research.

I had to learn that unless I promoted our research in the public domain, I would receive no funding.

Australian scientists should be taught this as one of their responsibilities.

A neighbour of mine, the late Don Kinsey, was a former engineer and one of the best fundraisers the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne has ever had. He ran courses for doctors so they could learn the right language to use to explain their research ideas to the public.

That need is just as important now as it ever was. In fact, it can be helpful to a scientist to restructure her or his research to achieve productive outcomes.

I am surprised you would say I’ve had an incredible career and success. Certainly, helping deaf people turned out much better than I dreamed.

It’s even more exciting. In the early days of the cochlear implant or bionic ear, it was simply very new on the horizon.

But now there are many new things as we know, like artificial intelligence. We’re looking at more connections between engineering and medicine – even at a micro level.

I’m excited by it all. I’d like to start all over again.