Politics & Society

Deciphering the legacy of Danism

With various Australian elections on the horizon, it shouldn’t be a surprise Labor governments are distancing themselves from the CFMEU. It’s happened throughout their history

Published 22 July 2024

The Australian Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union (CFMEU) has been in the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

An in-depth investigation by the Nine papers and 60 Minutes revealed connections between the union’s Victorian leadership and organised crime, as well as evidence of corruption and intimidation on worksites.

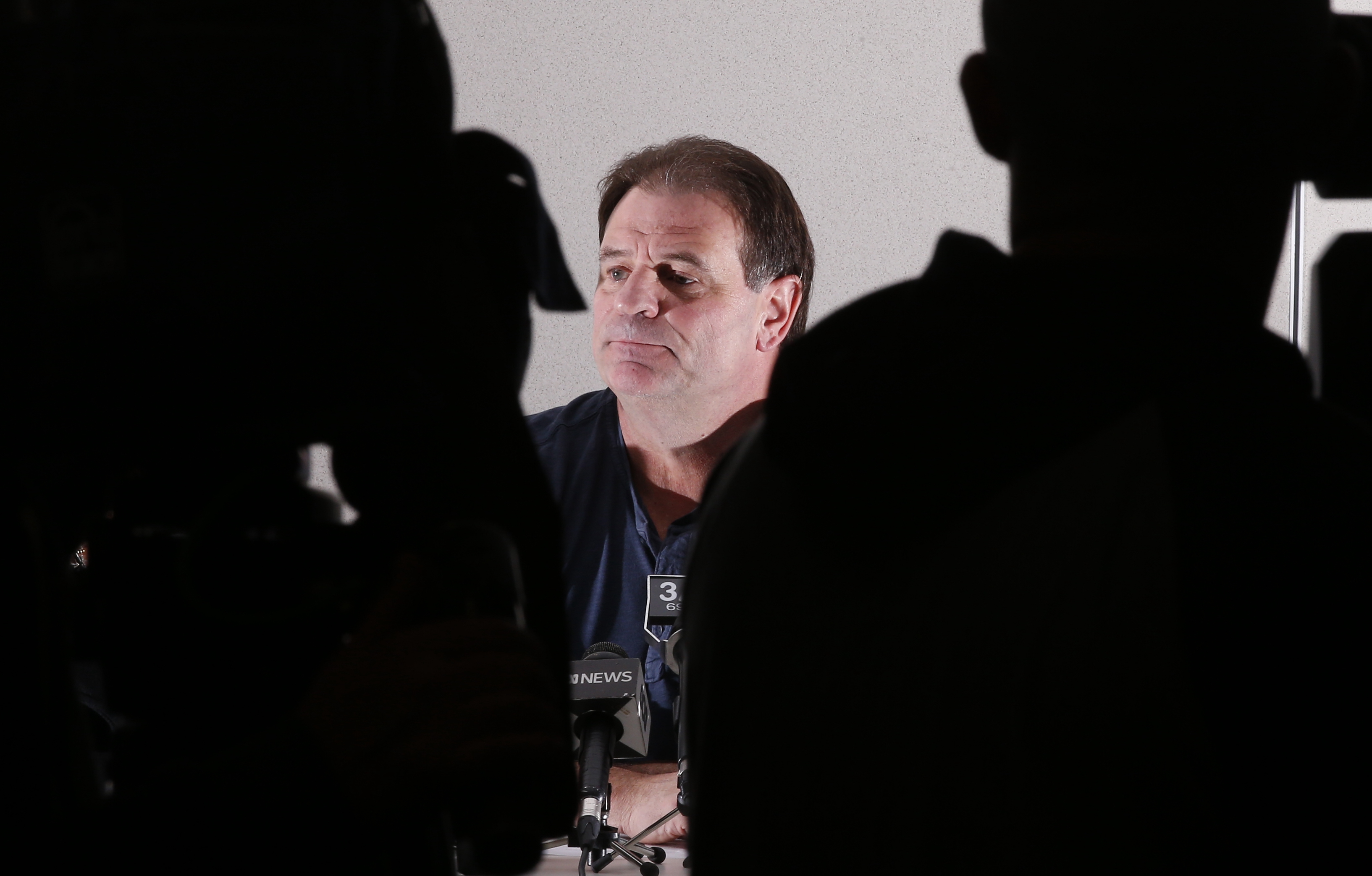

Victorian secretary of the CFMEU, John Setka, has resigned, several state branches of the union have been placed into administration, and the CFMEU’s construction arm has had its affiliation with the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian Council of Trade Unions suspended.

This will certainly not be the end of the consequences for the CFMEU. There are ongoing investigations, prosecutions and inquiries.

The Minister for Industrial Relations, Tony Burke, has said he is exploring the full gamut of state interventions into the union. Indeed, he said he is willing to go all the way up to the nuclear option: de-registration.

De-registration means the union would not be officially accepted as a representative of workers under the Fair Work system: it would mean the CFMEU could not get award coverage for any workers, would lose all its rights under the law to site access and information and could not take protected industrial action.

Politics & Society

Deciphering the legacy of Danism

Depending on how governments go about it, de-registration might even require all members resign from the union if they want to continue working in their sector. It would likely mean the end of the union altogether.

Since that initial uttering of the ‘D’ word, the government has demurred, claiming de-registration is not their preferred option, but the Prime Minister has maintained “nothing is off the table”.

So, while it may not be the most likely option, de-registration does seem to be something Labor thinks is a potential response to the problem.

This is not the first time the CFMEU has found itself the target of a government crackdown. The Morrison Government’s Minister for Industrial Relations, Christian Porter, once called the union the “most unlawful organisation in the history of Australia’s industrial laws”.

That, of course, is overstating the case, and part of the union’s ‘lawlessness’ is actually a product of Australia’s incredibly restrictive rules around unions and striking – rules the CFMEU has broken repeatedly in their (highly successful) quest to extract better pay and conditions from a notoriously brutal, dangerous, often-times corrupt industry.

But there are vices like hard-ball tactics that flout unjust anti-union laws, and then there are vices like hiring convicted killers and bikies as ‘health and safety reps’, or using gangsters to intimidate contractors, or taking bribes from developers in exchange for endorsing them for a big government contract – not so much a case of pushing the boundaries of industrial law; more a case of union leaders operating like a kind of mafia.

Even still, de-registration would be a highly draconian response.

Obliterating the union is not an obvious cure to the disease of a leadership seemingly engulfed in organised crime and corruption. If that were really the target, there are more precise, less destructive ways to get at it.

This would wipe the CFMEU off the map entirely.

Politics & Society

Broken parachutes

The question is why.

The answer becomes clearer when we look at history, for we have seen eerily similar episodes before. Indeed, one of the CFMEU’s predecessor unions, the Australian Builders’ Labourers’ Federation (BLF), faced similar claims about corruption and intimidation, about ‘lawlessness’ and criminality, and similarly faced the threat of – and ultimately fell victim to – de-registration.

Like the CFMEU, the BLF long held Australia’s regulations around unions and striking in contempt. That attitude frequently put the union on the wrong side of the courts, and their organisers on the wrong side of bars.

But more so than the CFMEU, the BLF performed incredible feats in elevating impoverished and neglected workers to a position of dignity and security.

The union’s illegal strikes, its pickets and project bans, its use of guerrilla tactics against builders – like the BLF special, the ‘interrupted concrete pour’ – saw the union make huge gains for builders’ labourers, without (and often in spite of) industrial tribunals.

The BLF became a force to be reckoned with inside the industry. That also made the union a major target.

By the early 1980s, Coalition governments set out to destroy the BLF’s stranglehold on the construction game.

The Fraser Government in Canberra and the Thompson Government in Victoria initiated a joint Royal Commission into the union, and, simultaneously, started proceedings to de-register the union.

The Royal Commission heard evidence that the BLF’s long-serving Victorian and Federal Secretary, the colourful Norm Gallagher, had accepted bribes from building developers in the form of free materials and labour for family holiday homes on the Gippsland coast, in exchange for industrial peace (quite a similar scheme to the CFMEU’s alleged kick-back plan).

Politics & Society

Rebuilding Victoria’s forgotten integrity institution

Gallagher always maintained his innocence, and the BLF waged a long series of strikes and protests in retaliation for their leader’s alleged persecution. Gallagher was ultimately jailed in Pentridge Prison for several months.

His jailing was the beginning of the end for the BLF. After the revelations about alleged corruption and a fresh series of violent incidents on union pickets, de-registration was begun in earnest.

The final plunging of the knife came not from the Coalition but from Labor: Neville Wran in New South Wales, John Cain Jr in Victoria and Bob Hawke in Canberra all moved against the union – not simply de-registering it but passing laws outlawing membership for workers in the industry.

The most aggressive measures to break up the BLF came in Victoria, where police turned out in massive numbers on worksites, rounding up labourers and forcing them to sign resignation letters or be banned from the site.

But all the militancy in the world could not protect the BLF from the full might of the state – members migrated into other unions, including the CFMEU, and the BLF was crushed.

Even if the allegations about corruption and violence on worksites were true – and there remain steadfast BLF-supporters to this day, who claim the charges were trumped up by those offended by union militancy more generally – de-registration was a remarkably draconian anti-labour measure, particularly for a series of Labor governments to take.

Bear in mind, this is a party ostensibly founded to shield the union movement from the oppression of the state.

The trigger for the formation of the Australian Labor Party was the breaking of a major series of strikes in the 1890s by colonial parliaments sending in police and troops.

Unionists decided they needed a parliamentary party that could stop governments doing that.

Politics & Society

Misleading conduct? So what!

It is not a mission, though, that the Labor Party has lived up to.

In fact, since its formation Labor has been more prone to sending in the military to break up strikes than the other side of politics.

In 1949 it was a Labor Government – of Labor hero Ben Chifley – that sent in the army to break up massive strikes by coal mining unions. In 1989, it was Bob Hawke’s Labor government that despatched the RAAF to break a Qantas pilots’ strike.

And while Coalition governments – like Fraser’s, or John Howard’s, or Malcolm Turnbull’s – have instituted commissions to investigate trade unions, including some specifically targeting the construction sector, it has been Labor governments that have actually done the deed of killing troublesome unions off.

The mooted de-registration of the CFMEU is really further evidence supporting the notion that Labor is not in fact a party of labour. Sure, the ALP is clearly more sympathetic to unions than the Coalition, and Labor retains formal and personnel links to the movement, but looking at its record, it is clear Labor is a fair-weather friend of unionism.

When unions have behaved badly, or even when they have simply been militant about protecting the rights and dignity of their members, Labor has shown a willingness to turn on them.

The ALP is, ultimately, an independent electoral machine. Its political fortunes rely on cultivating a broad constituency: it is what’s called a ‘catch-all’ party, not really a ‘sectional’ party that advocates for a particular group, like working people or unions.

Where Labor’s interests have diverged from the union movement’s, the party has pursued their own mercilessly.

With various Australian state and federal elections on the horizon, it should probably be no surprise Labor governments are eager to create as much distance between themselves and the CFMEU as possible.

In fact, they may well go further than the Coalition might have gone in smashing the union, simply to demonstrate their independence.

Rather than engaging in the more painstaking work of rooting out corruption and criminality in the union, Labor may well end up sacrificing the entire organisation on the altar of electoral popularity.