Politics & Society

Nowhere people have a right to somewhere

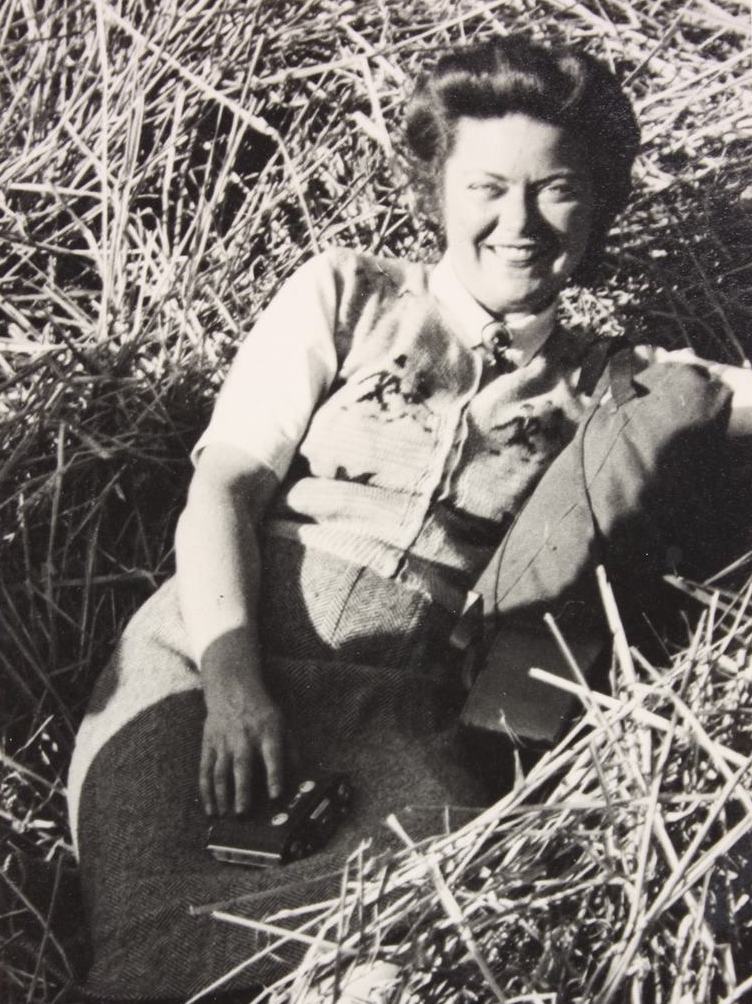

In the aftermath of World War II, Australian woman Esma Banner travelled to Germany to work with the UN in resettling the millions of post-war refugees. On World Refugee Day, we look back at the personal insights offered by her letters, diaries and photographs

Published 19 June 2017

Since civil war erupted in Syria six years ago, millions of refugees have made the perilous journey, by land and sea, to Europe, to escape bloodshed and conflict. It’s been referred to by organisations like the United Nations as the “biggest refugee crisis since World War 2”.

In today’s digital and image-focused world, photographs create a visual landscape of this civil war – over-crowded camps for the displaced, orange life jackets on crowded boats, and lifeless, small bodies washed up on distant beaches.

But these current images have echoes dating back more than 70 years ago, following the end of the Second World War.

At the conclusion of hostilities in 1945, an Australian woman, Esma Banner, left her home in New South Wales to become one of 39 Australians working in Germany with the United Nations helping refugees.

She recorded her experiences in diaries, letters and photographs. And while she was not able to share them with others as quickly as is possible today, Esma sent her pictures and words home to family – telling them about the reconstruction work she was carrying out.

The end of World War II saw one of the largest population movements in European history. By some estimates, around 60 million Europeans became refugees during World War II.

The United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Administration (UNRRA) was established in 1943 to provide assistance to victims of war in areas controlled by the United Nations, and to assist people to return to their home countries in liberated areas. Three years later, the UN set up another agency, the International Refugee Organisation (IRO), to focus on the resettlement, rather than repatriation, of refugees and displaced people.

And it was here, in the UN’s displaced persons camps in Germany, that Esma Banner was employed.

Esma was born in 1910 in NSW. During the war, she was an ambulance driver for the National Emergency Services but at the conclusion of the war she applied to be a driver with UNRRA. Esma started work almost immediately and was soon accepted to work in the US-controlled zone of Germany. She arrived in September of 1945 and began work initially in the administration of the camps, before moving into the health division. This was not work Esma was specifically trained to do, but skills she learned on-the-job.

The camps were set up by Allied and Soviet forces as temporary hubs for people displaced during the War. However, they soon became long-term locations that not only provided food and shelter, but also medical care, employment, education and recreation for those who could not, or did not want to return to their countries of origin. Many of these camps remained in use until 1952.

Esma was already a keen amateur photographer. During her six years working in Germany between 1945 and 1951, she diligently documented her life there and her work.

In 1948, Esma proposed a photo exchange plan with her younger sister Madge. She planned to use the photographs her sister sent over to make an album, keeping her up-to-date and involved with goings on back in Australia. The idea was put to Madge: “How about it? No snaps from you, then none from me and vice versa”. As a result of this deal, the documentation she left behind is insightful providing us with personal reflections and information beyond official documentation.

Esma was explicit about the place of photography she saw in maintaining these connections. In another letter home she said: “You are all always in my thoughts – every picture I take is for you”.

Politics & Society

Nowhere people have a right to somewhere

Her photography and writing offers an insight into how she learned to be a post-WWII rehabilitation and migration worker. We get glimpses of her trying to make sense of the post-war landscape, particularly difficulties some displaced people faced trying to migrate.

Esma’s written record highlights some of the frustrations faced by the people displaced in the camps. In several letters she discusses the plight of those who want to emigrate but cannot.

She also recounts some of the “incredible” stories of children refusing to be repatriated that were told to her by a nurse, Miss Dyke in charge of a children’s centre: “Some of the stories of the older boys at the Centre are almost incredible. One fair-haired boy saw both parents killed. Another arrived home from school and found his complete family gone – so he lived with neighbours until they were rounded up and taken too. When asked why they don’t want to go back to Poland they say political reasons and this from under 14s”.

She was supportive of immigration. In 1946, she wrote that “Australia would benefit from an influx of varied people, but of course everyone is so afraid of losing something by letting others in”. We get another insight into her opinions in the caption of a photograph of a group of smiling children whose parents she defines as having “no immigration chance”.

In a diary entry, likely written in 1952 after she had returned to Australia, she reflected on a number of difficult situations for refugees. One she described in detail was, she said, a “classic example of the red tape which cannot be cut”. It outlined the experiences of a woman, her husband and their five children aged between one and seven. While the family were being processed for emigration to the United States, the husband “mentioned he was born in some town in the US”.

This was verified and meant “the family were not DPs but dependants of a US citizen”, so could only enter the US after the husband was established and residing there. Despite this, the family were treated as DPs by the International Refugee Organization and living in the camp. Esma was updated after she arrived back in Australia that the “latest information” was that the women had TB and was not able to accompany her children to the US. Esma concluded that her “struggle to care for all these tots … and the worry in not hearing, sometimes for months, from her husband no doubt was mainly responsible for this”.

In 1950, when Esma’s father and sister both became ill, she wrestled to make the decision to leave her professional life as a relief worker and return home, writing “I would like to stay here for 9 or 12 months as the job has become very intense and I feel I am at the stage of really learning something”. But family came first and she arrived back in Sydney in early 1951.

Esma’s work in the displaced persons camps in Germany was recognised with an IRO Service Medallion. But, according to her niece, she kept in touch with some of the displaced people she met while working in Germany; some of whom visited her home once they had resettled in Australia.

Esma Banner wanted to be involved in the reconstruction of the post-war world. She wanted her family and people in Australia to learn about it too, and considered this work important enough to document not only for her family, but for future generations.

Museums Victoria now plays home to The Esma Banner Collection which is composed of more than 1000 objects, documents and photographs bringing together a picture her experiences in Germany. This collection retains ongoing cultural relevance to the large migrant communities as well as numerous people connected to post-WWII migration to Australia.

Banner: “Children of DPs (displaced peoples) with no immigration chance”/National Archives of Australia