Politics & Society

Timor-Leste’s political impasse

Malaysia’s ruling coalition had been in power for 61 years, until this month. But what do the unexpected election results mean if viewed through the lens of constitutional rights and the rule of law?

Published 17 May 2018

Against all but the most optimistic expectations, voters in Malaysia’s 14th General Election held this month emphatically rejected the long-serving Barisan Nasional (BN - National Front) government of Prime Minister Najib Razak in favour of the Opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH - Alliance of Hope) coalition, led by the country’s former PM, 92-year-old Mahathir Mohamad.

To understand just how remarkable this is, it’s necessary to look at Malaysia’s political history.

The PH alliance won 121 of the 222 seats in Malaysia’s the Dewan Rakyat, or lower house. Their victory marks the first time since Malaysia’s independence in 1957 that Najib’s United Malays National Organisation (UNMO), the largest party in the BN coalition, will not be leading the government.

Beyond overturning more than six decades of entrenched incumbency, this election saw a significant number of voters move beyond Malaysia’s habitually race-based politics.

Over the last decade, the BN coalition has increasingly abandoned its multi-racial roots, with rising use of the rhetoric of Islamic supremacy and exploiting fears of competition from the minority Chinese and Indian communities.

Politics & Society

Timor-Leste’s political impasse

The winning PH coalition attempted to run as the multi-racial, multi-faith coalition that BN once aspired to be. The second largest party in the PH coalition, the Democratic Action Party (DAP), is predominately Chinese and avowedly secular.

But the most surprising aspect of the PH victory is that it occurred under the profoundly oppressive nature of UMNO-BN’s long rule. Successive BN governments have distorted and weakened public institutions, from the courts and the Attorney-General’s office to the Anti-Corruption Commission and the Electoral Commission.

Under these circumstances, the capacity and willingness of voters to cast their votes for PH is, frankly, heroic.

In the many post-election reports flooding Malaysian and international news media, commentators are explaining the scale of UMNO-BN’s defeat by referencing the complex electoral demographics; the rising cost of living and a deeply resented GST; as well as the impact of entrenched corruption and the colossal financial and other scandals that have swirled around Najib for the last decade.

But, we also need to see the significance of this election through the lens of the Malaysian Federal Constitution.

The Constitution establishes a federal, parliamentary democracy in a secular state presided over by a constitutional monarch. The executive, legislative and judicial branches are separated in a manner designed to perform the checks and balances typical of the Westminster system.

There is universal franchise, and elections for the lower house of the federal parliament must be held every five years under the supervision of a constitutionally mandated Election Commission (EC) which must be constituted to ensure ‘public confidence’. Civil and political liberties – including personal liberty, due legal process, equality and non-discrimination, and freedom of speech, assembly, association and religion – receive express protection.

Politics & Society

Is Australia becoming the ‘lonely’ country?

On paper, Malaysia looks like a secular liberal democracy, designed on sound rule of law principles, and with clearer constitutional protection of fundamental liberties than Australians enjoy. These are the political and legal foundations of Malaysia, and the basic standard to which citizens should be able to hold their governments and public institutions. But the reality is very different.

Constitutional rights are curtailed by draconian legislation, and they are denied or eroded by government (and police) policy and action, through things like selective and politically-motivated prosecutions. The courts have sometimes been willing to take a robust view of citizens’ rights and the rule of law. But more generally the Malaysian judiciary has a reputation for caution and deference to the executive, especially when deciding cases concerning public order or the powers of state Islamic institutions.

As the annual and ad hoc reports of Malaysian and international human rights and democracy monitors show, UMNO’s Malaysia is at best a ‘flawed democracy’, perhaps better understood as a semi-authoritarian regime.

Nowhere is this better demonstrated than the 2016 gazettal of the National Security Council Act, which, simply put, creates the apparatus for the Prime Minister to invoke dictatorial powers unfettered by parliament or the courts.

The UMNO regime’s disregard for the rule of law, democracy and constitutional rights was revealed starkly as election day approached.

Examples include the fact that some of PH’s most effective MPs were barred from re-contesting their parliamentary seats due to convictions for essentially political offences - Rafizi Ramli for revealing confidential information when blowing the whistle on a government linked financial scandal, and Tian Chua for insulting a police officer.

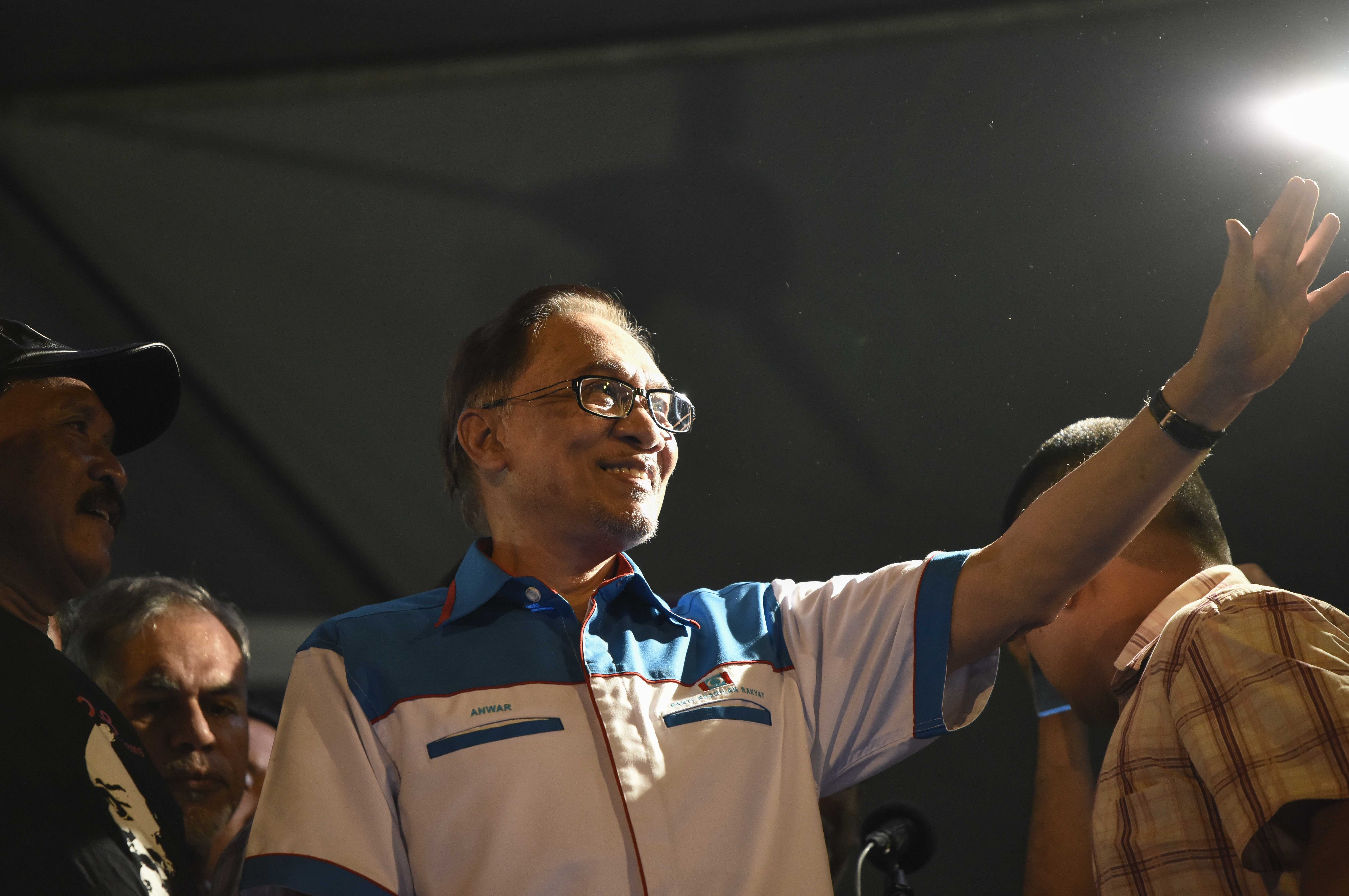

As is well known, PKR leader Anwar Ibrahim was convicted – for the second time – of politically-motivated charges of sexual misconduct and has been in prison since 2015. He has been swiftly released following the election and given a royal pardon, transforming a political prisoner into a prime minister-in-waiting.

Politics & Society

Phantom democracies

Additionally, the EC recently completed a new electoral delineation exercise plainly designed to advantage UMNO. The Malaysian Bar condemned it as ‘fundamentally flawed, inherently unfair and unconstitutional’ and the Malaysian Human Rights Commission castigated the EC for denying citizens their constitutional rights to participate in public affairs through a free and fair voting system.

The Registry of Societies suspended Mahathir’s party (PPBS) on spurious grounds, effectively preventing it from campaigning under its party slogans and logo.

On the official day to nominate candidates, the EC imposed a completely unnecessary requirement for a pass to enter the nomination hall, and then, in circumstances that arguably amount to misfeasance in public office, declined to accept the nomination of a PH candidate who was unaware of the requirement. At close of nominations, the EC declared the UMNO candidate elected unopposed.

Hoping to drive down turnout to the government’s advantage, the election was held mid-week instead of the usual weekend, making it very difficult for voters to return from urban workplaces (and Singapore) to their home constituencies.

And although support for the PH is high amongst Malaysians based abroad, the EC failed to send many overseas voters the correct forms or sent them too late for return by post. In a truly inspiring initiative, Malaysians from Finland and New York to London and Melbourne formed relay teams to collect ballots and fly them back to the correct Malaysian polling stations in the nick of time to be counted.

And so on.

As election day approached, the barriers to genuine democratic participation in the election seemed insurmountable. Given these obstacles, the scale of UMNO’s defeat is a clear measure of the profound depth of popular dissatisfaction with its rule and a strong desire for a new beginning. So great are the expectations placed upon PH that there is now excited talk about a ‘rebirth’ of the nation.

Is PH well equipped to meet those expectations? Will the coalition of democratic non-Malay secularists and (mostly) Muslim Malay nationalists hold? Has Mahathir, whose previous stint as the 4th UMNO PM from 1981 to 2003 actually consolidated authoritarianism in Malaysia and did so much to harm the independence of the courts, really become a born-again democrat?

Business & Economics

In praise of technocracy: Why Australia must imitate Singapore

Nothing he has said since being sworn suggests he has a developed a better appreciation of the separation of powers. Will a PH government led by Mahathir – and then by Anwar Ibrahim, if that succession plan holds – be prepared to surrender the awesome powers of the National Security Act? Will it forego the power to punish critics under the Sedition Act?

We would be foolish to predict just yet, as news continues to break at a dizzying pace and it is impossible to keep up. Mahathir is already publicly at odds with his new Finance Minister, DAP leader Lim Guan Eng, over the desirability of repealing Najib’s draconian Anti-Fake News Act, and the post of Attorney-General sits vacant.

Ideas, proposals and counterproposals are swirling around as PH political operatives think aloud and current affairs sites carry commentaries like this one. But in its search for a way forward, PH should first go back to the constitution.

It’s not perfect, and some things need urgent repair. But it’s not too bad either, and it seems a good place for a new government to start.

A version of this article also appears on Election Watch.

Banner: Getty Images