Mapping back to a lost childhood

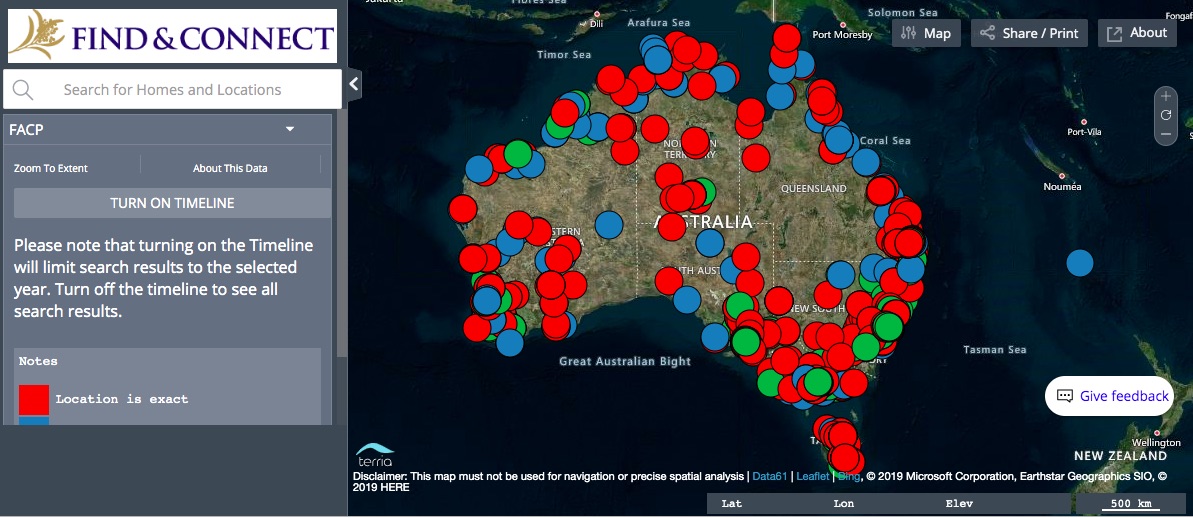

A new interactive online map of Australian care homes is helping those who grew up in care track down the institutions they stayed in, and their records

Published 16 October 2019

The woman had grown up in a care home, but she couldn’t remember the name of the home and had no way of finding it on her own. All she remembered was that it was somewhere in western New South Wales, that it was run by nuns, and there were cows on the grounds for milking.

With just these details to go on she faced a tough, if impossible, task in tracking down the records that the home may have created about her. These records could be the only source of information about who she was, what had happened to her, and where she had grown up.

Her predicament isn’t uncommon among the many people who were taken from their parents and placed in institutional care. Now adults, they want to know more about their childhood and contact us at Find & Connect for help in finding any information they can.

Many tell us that it is only as their own children grow that they start to feel the gaps in their own childhood more keenly. They’ve been too busy getting their lives on track, working and taking care of their own family to look back, and many more haven’t wanted to revisit what may have been a difficult past.

The Find & Connect web resource, run at the University of Melbourne, was established by the Commonwealth Government to help the 500,000 people who grew up in institutional care between 1920 and 1989 track down and access their archival records.

But this isn’t easy for those struggling to remember details from their childhood, especially given the complex trauma that many experience after being taken from their family and placed in the welfare system.

Which is why we have now developed an interactive geographic map of Australian Children’s Homes to better help people discover essential information about their lives.

The map works with the memories people have about the homes they were in – an approximate location, whether it was a religious institution, or any outstanding landmarks that existed when the person was in the home.

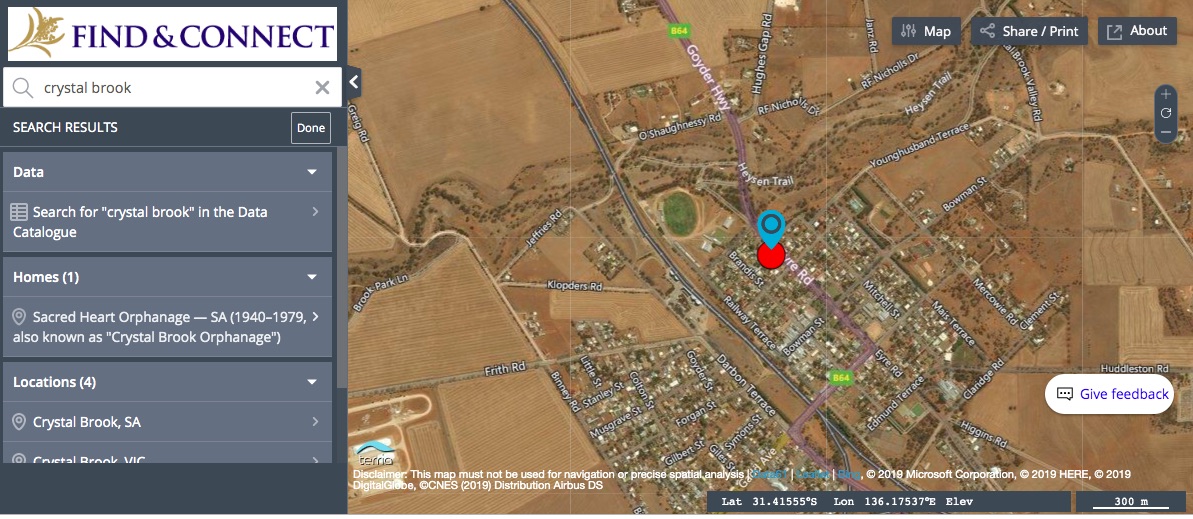

It means sketchy information, like memories of nuns or livestock, and a vague location can be enough to locate the exact home where a person spent their childhood.

Once that home has been identified, important records, sometimes including medical information or the names of parents and family members, can be provided to the person seeking to fill in the gaps in their lives.

Arts & Culture

What history can really teach us

Frank Golding, who spent time in care as a child and helped us to develop the map, has over the years has assisted many people like himself search out information about their past. He is well aware of the many stumbling blocks to locating both the home a person spent time in, and the records from their time in care.

“When Homes had common names, like St Joseph’s, it can be confusing, and sometimes former residents are not sure which of the Homes was theirs, or if the Home they grew up in has been demolished to make way for redevelopment, the new structures can confuse their memory of where it once stood.”

Jeremy Palmer is a Records Management Officer at Wattle Place in NSW. He assists people who grew up in care to locate and access their records, and any other information about institutions where they were residents.

He says the map is particularly useful for people who only remember a vague location of where they were, which makes the homes difficult to find without being able to view them in context to surrounding areas.

“By seeing where the homes are located on the map it is very easy to know that another home in another suburb is only a kilometre or two down the road and may therefore be relevant to the searching,” he says.

Over 2000 institutions are included on the map and each can be found by zooming in to a particular area or suburb. The map can also be searched by timeframe since the time someone was in care can also help locate the particular home they are searching for.

For example, if someone knows they were in care around Ballarat between 1965 and 1975, they can narrow the search parameters down to homes that only existed in that place and time.

Politics & Society

Helping care leavers find and connect to their past

As many useful details as possible have been included on the map to help in the search for a lost home. As well as being able to search for information specific to a home, landmarks and other details that can prompt memories have also been included.

For example, feedback from people who grew up in Queensland showed that while they may not remember the name of a specific home, they do remember that it backed on to pineapple farms.

The map is searchable, so people can either click on specific regions, or specific homes in those regions, or filter searches by aspects they remember.

They will then be able to find more information about the home, including any photographs that exist, a history of the home, and if records that were created about the children were kept.

The map will be life changing for those who thought their childhood was lost to them forever.

Some people may find content of the Find & Connect website distressing. For support contact the Find & Connect Support Services: Freecall 1800 16 11 09 (Monday–Friday 9am–5pm) or Lifeline: Call 13 11 14 anytime for confidential telephone crisis support.

The map is available on the Find and Connect website.

Banner: Children from the Roberts Home, South Australia, sometime around 1949-50. Picture courtesy of Peter John Tate.