Health & Medicine

Why the number of dementia cases has doubled

Dementia is the leading cause of death in Australian women and the second leading cause of death for Australians overall. Dementia prevention must be prioritised

Published 16 September 2021

There are an estimated 472,000 Australians currently living with dementia, which is expected to exceed 1,000,000 by 2058.

Taking a global view, one person develops dementia every three seconds and the estimated cost of dementia (US$818 billion in 2015) makes it equivalent to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the eighteenth largest country in the world – ranking in-between the GDP of the Netherlands (17th largest) and Switzerland (18th largest).

Recognition of the importance of dementia prevention has been increasing internationally. The World Health Organization has taken a lead role by publishing Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia guidelines in 2019.

Given that we are now in the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing though until 2030, it is a good time for us to ask ourselves – what can we do to prevent dementia?

While we acknowledge that dementia isn’t completely preventable because some risk factors – like our genetics – cannot be changed, the good news is that according to current knowledge around 40 per cent of our dementia risk can potentially be addressed.

Health & Medicine

Why the number of dementia cases has doubled

And it comes down to public health policy.

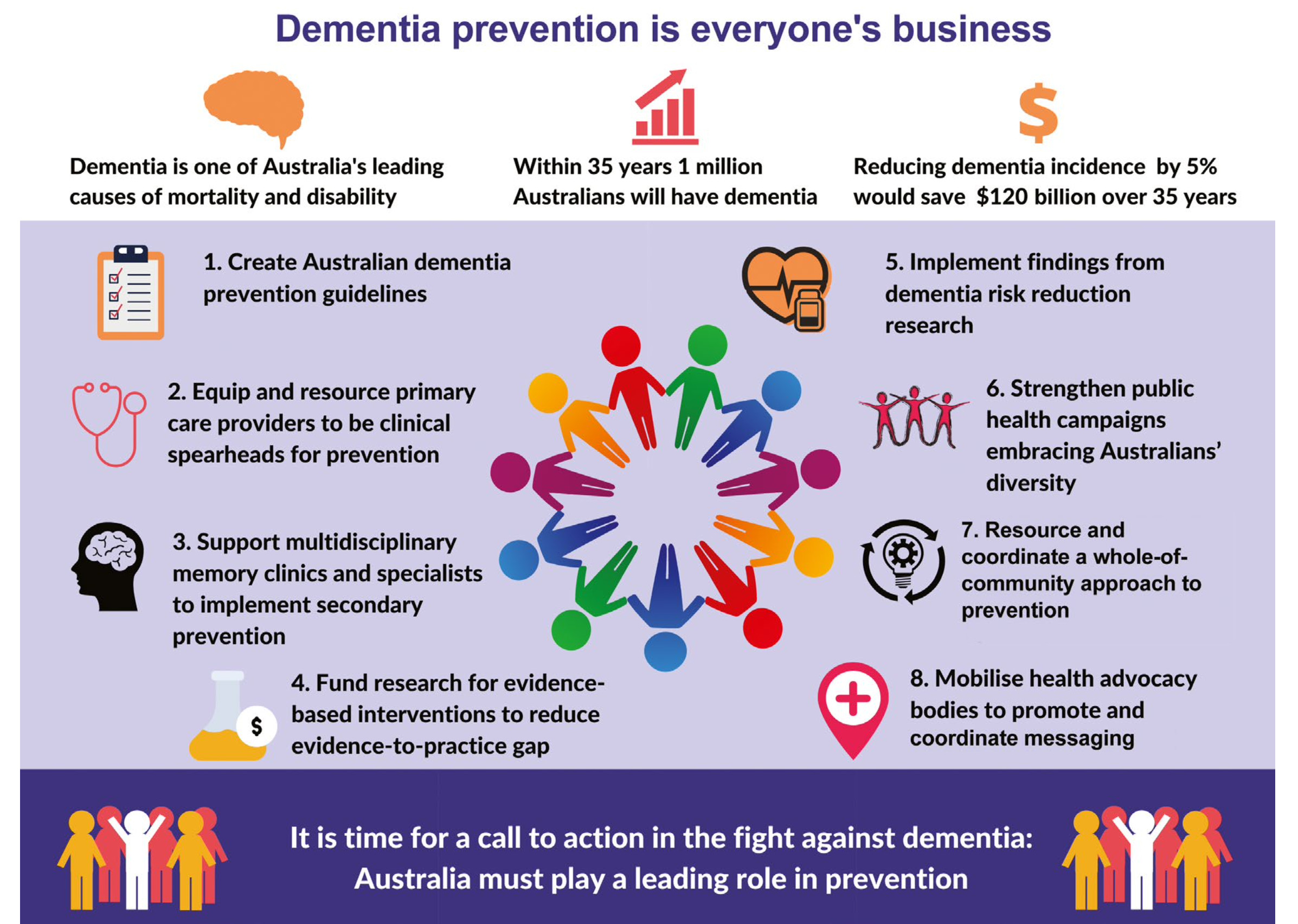

Our team, along with other professional colleagues, recommend an eight-step dementia prevention action plan for Australian health policy:

1. Create public health and clinical practice guidelines for dementia prevention across the lifespan for Australia;

2. Equip and resource primary care providers to be the clinical spearheads for dementia prevention throughout life;

3. Support multidisciplinary memory clinics and specialists to implement secondary prevention programs for those at high risk;

4. Fund research for evidence-based interventions for modifiable risk factors for dementia across the life cycle to reduce the evidence-to-practice gap;

5. Implement findings from dementia risk reduction and implementation research through translation into health promotion programs;

6. Strengthen dementia prevention public health campaigns embracing Australians’ diversity, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians;

7. Resource and coordinate a whole-of-community approach including government, public and private health care, community services and education sectors to operationalise guidelines and multifaceted dementia prevention programs throughout life;

8. Mobilise peak health advocacy bodies to promote and coordinate public health messaging on dementia risk factors that cut across chronic conditions.

Arts & Culture

How music could revolutionise dementia care

If we look at the situation in Australia, the population-attributable risk (PAR) of dementia risk factors are physical inactivity (17.9 per cent), mid-life obesity (17.0 per cent), early life low educational attainment (14.7 per cent), mid-life hypertension (13.7 per cent), depression (8.0 per cent), smoking (4.3 per cent), and diabetes mellitus (2.4 per cent).

The PAR refers to the percentage of dementia that could be prevented, if the risk factor was completely removed. For example, if all Australians undertook the recommended amount of physical activity, 17.9 per cent of dementia in Australia could be prevented.

It is all very well to quantify these risk factors, however, there are significant challenges.

Firstly, identifying these risk factors in individuals, especially in mid-life adults, who are much less likely to see healthcare professionals and undertake preventative health care is difficult.

On top of that, translating this knowledge into action isn’t as easy as it should be – many of us know from experience that being aware that we should be physically active doesn’t necessarily translate into action.

But there’s growing research into the area of ‘behaviour change’ which is a critical part of translating knowledge into action.

Health & Medicine

Diagnosing dementia in younger people

Our team at the Academic Unit for Psychiatry of Old Age has been addressing dementia risk reduction through a number of different research projects.

We have recently published Physical Activity Guidelines for older Australians with memory concerns. An interventional approach was the INDIvidual GOal-setting study or (INDIGO) project. This investigated the effectiveness of a physical activity program with individual goal-setting and volunteer mentors for physically inactive older adults at risk of cognitive decline.

Seventy eight year-old Eunice Cooper participated in the INDIGO project in 2013, and reflects back on her participation.

“I needed to improve my walking strength so I could do a refresher course for basic swimming, and also in preparation for getting a dog.

“Because of the way the exercise began I would recommend it to anyone. After the program finished, I joined a walking group for four years and later due to hip issues and not wanting an operation, I went to physiotherapy class for two years.

“Then COVID came up and I have discovered how adaptable I am. The INDIGO course for me certainly was a step in the right direction. And if I feel as though I’m not going to do anything all day, I put Gold FM on and jog on the spot, hands on the bookcase for balance until the record is finished at my top speed. It’s a real mood changer, fresh energy running through my veins.”

Two of our new research projects also address dementia prevention in different ways.

The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF)-funded EXercise for Cognitive hEaLth (EXCEL) project aims to remotely deliver an individually tailored physical-activity interventions to people living in the community, aged 45-80 years, who experience mild to moderate symptoms of depression or anxiety, as well as have concerns about their memory.

Health & Medicine

Alzheimer’s disease during a pandemic

The aim is to improve mental health and reduce dementia risk through using behaviour change techniques to encourage physical activity.

This remote intervention delivery not only addresses the challenges of COVID-19, but also helps reduce Australia’s “tyranny of distance” as it increases accessibility to those in rural or remote areas.

Our other study, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), is the Leveraging Evidence into Action on Dementia (LEAD) project. This is a collaboration with researchers from the University of New South Wales and other institutions.

The project aims to co-design a tool that can estimate an individual’s risk for multiple conditions at once – including dementia, diabetes, heart disease and stroke. This would streamline risk assessment and help to facilitate preventative healthcare especially in primary care.

Currently, we are interviewing general practitioners and undertaking a community survey to find out about opinions and preferences to guide the co-design of this tool.

We are inviting interested potential participants to contact us regarding the EXCEL and LEAD projects.

Australia has numerous examples of highly successful public health prevention campaigns. For example, the Quit Smoking and Slip, Slop, Slap campaigns have been so effective that virtually all of us are aware of them.

Some of the success of these campaigns can be attributed to their “whole of society” approach, from reinforcement in health settings and schools, to the general community and mass media.

There’s no more time to lose for Australia to apply its tremendous expertise in public health now to prevent dementia so that we can begin to turn around the concerning estimates of rising prevalence, disability, mortality and future costs.

If you are interested in becoming involved in the EXercise for Cognitive hEaLth (EXCEL) and Leveraging Evidence into Action on Dementia (LEAD) projects, you can find more information on the project websites.

Banner: Getty Images