Health & Medicine

Remembering Australia’s polio scourge

Before there was a vaccine, one polio treatment used infected blood to create a serum. But there are lessons to be learned from the past when it comes to COVID-19

Published 10 July 2020

Scientists are still working to understand whether the blood plasma of people who have recovered from COVID-19, which potentially contains antibodies against the virus, could be used as a treatment for coronavirus patients.

The jury is still firmly out when it comes to the research – one recent study from China was unclear about any benefit, and another from Johns Hopkins University in the US offered a hint of potential.

But, this isn’t the first time that a treatment like this has been proposed for a disease for which there’s no current treatment or prevention.

HISTORY REPEATING

A little over a century ago, in 1917, orthopaedic surgeon Dr Robert Lovett described what he was seeing:

Health & Medicine

Remembering Australia’s polio scourge

“No recent event in medicine has caused more anxiety that the epidemic of poliomyelitis during the summer of 1916 … the history of the 1907 epidemic and similar records give reason to fear extensive recurrences of the disease. … a humanitarian and economic problem of no mean dimensions.”

This was the situation in the United States of America, where of the 27,000 cases of polio reported in that country, half were in New York – with a fatality rate of some 26 per cent.

But many have since forgotten the virus that caused epidemics throughout the world for five decades before effective vaccines were developed.

Poliomyelitis, or infantile paralysis as it was initially known, frightened communities and governments around the world.

Schools, movie theatres, swimming pools and some interstate borders were closed. Families with affected members were ostracised and many despaired of ever finding a means of preventing the virus.

Before a vaccine was developed in the mid 1950s and introduced into Australia in 1956, one of the treatments used injections of serum taken from the blood of people who had recovered from the acute phase of polio.

The use of serum – which is plasma minus the clotting agents within blood – began to be used in the treatment of polio from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Health & Medicine

The science behind the search for a COVID-19 vaccine

The theory was that the serum of patients who had recovered from polio would contain antibodies which could potentially transfer to others in an attempt to prevent paralysis or lessen its severity.

Although no randomised clinical trials were undertaken, enthusiastic medical practitioners and pressure from worried parents promoted the approach.

THE AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH

Dr Annie Jean Macnamara graduated in medicine at the University of Melbourne in 1922 and, in 1928, became the honorary medical officer to the physiotherapy department at the Children’s Hospital in Melbourne.

Here, she managed the clinical care of hundreds of people with polio in Victoria, Australia.

Dr Macnamara also played an important role as medical officer to the Poliomyelitis Committee of Victoria. As one of the strongest medical proponents of the use of serum in Australia she influenced its use.

The Victorian polio epidemic in 1925 prompted Macnamara to test the introduction of immune serum in the treatment of pre-paralytic patients.

Health & Medicine

Public trust and controlling COVID-19

In most patients three or four days of a general illness including fever, vomiting, headache and constipation preceded paralysis. Often those who became paralysed experienced hand tremor, light sensitivity and urinary retention, but the most important symptom was severe pain when they bent their head forwards, flexing the spine.

If these symptoms were present and a lumbar puncture confirmed a polio infection, Dr Macnamara would inject serum intravenously and monitor the patient over the next twelve to eighteen hours in which passive immunity would be established by a marked improvement in the patient’s general condition and a rapid fall of temperature.

This serum was claimed to possess qualities that gave a patient protection against paralysis, and was promoted as an effective weapon against the effects of the poliovirus.

It offered hope in a time of uncertainty.

DISCOVERING THE STRAINS OF POLIO

Although Dr Macnamara continued to advocate and provide treatment with serum until the 1940s, research during the severe 1931 epidemic in New York indicated that serum didn’t prevent or appear to reduce paralysis.

Health & Medicine

Q&A: How could COVID-19 drugs work and what’s out there?

Despite this, serum continued to be used for more than three decades in the United States of America and elsewhere because “the public had become so aware of the fact that there is a serum for the disease that it is difficult not to administer it”.

In 1928, Dr Macnamara began working at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, with her fellow medical graduate and later Nobel prize winner, Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet.

Scientific discoveries often build on the previous work done by other researchers, and it is common to share material, hypotheses, methodology and results.

Dr Simon Flexner, a distinguished pathologist who served as the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, shared samples of the Rockefeller strain of poliovirus with Dr Macnamara and Professor Burnet in 1929.

They discovered that the samples from the Rockefeller Institute were more virulent than the strain in Victoria, indicating that more than one type of polio virus existed.

In 1931, Dr Macnamara and Professor Burnet published their discovery of the existence of more than one strain of polio virus, which flew in the face of the assumption that different strains were similar.

Their report was treated with scepticism – “it came from unknown investigators on a remote continent” – but their work went onto make a significant contribution a quarter of a century later to the development of the Salk and Sabin vaccines that made the fear of polio a thing of the past.

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

Despite our modern advances in science and the technology, it’s salutary to remember that more than six decades passed before effective polio vaccines became available.

It’s also worth remembering that the wild polio virus is still endemic in parts of the modern world.

So, when it comes to the current COVID-19 pandemic, there will no doubt be false starts and raised hopes when it comes to treating the virus. Until we get a vaccine.

And this time, researchers and scientists from this “remote continent” are being recognised for the research they are contributing to a global effort to discover one.

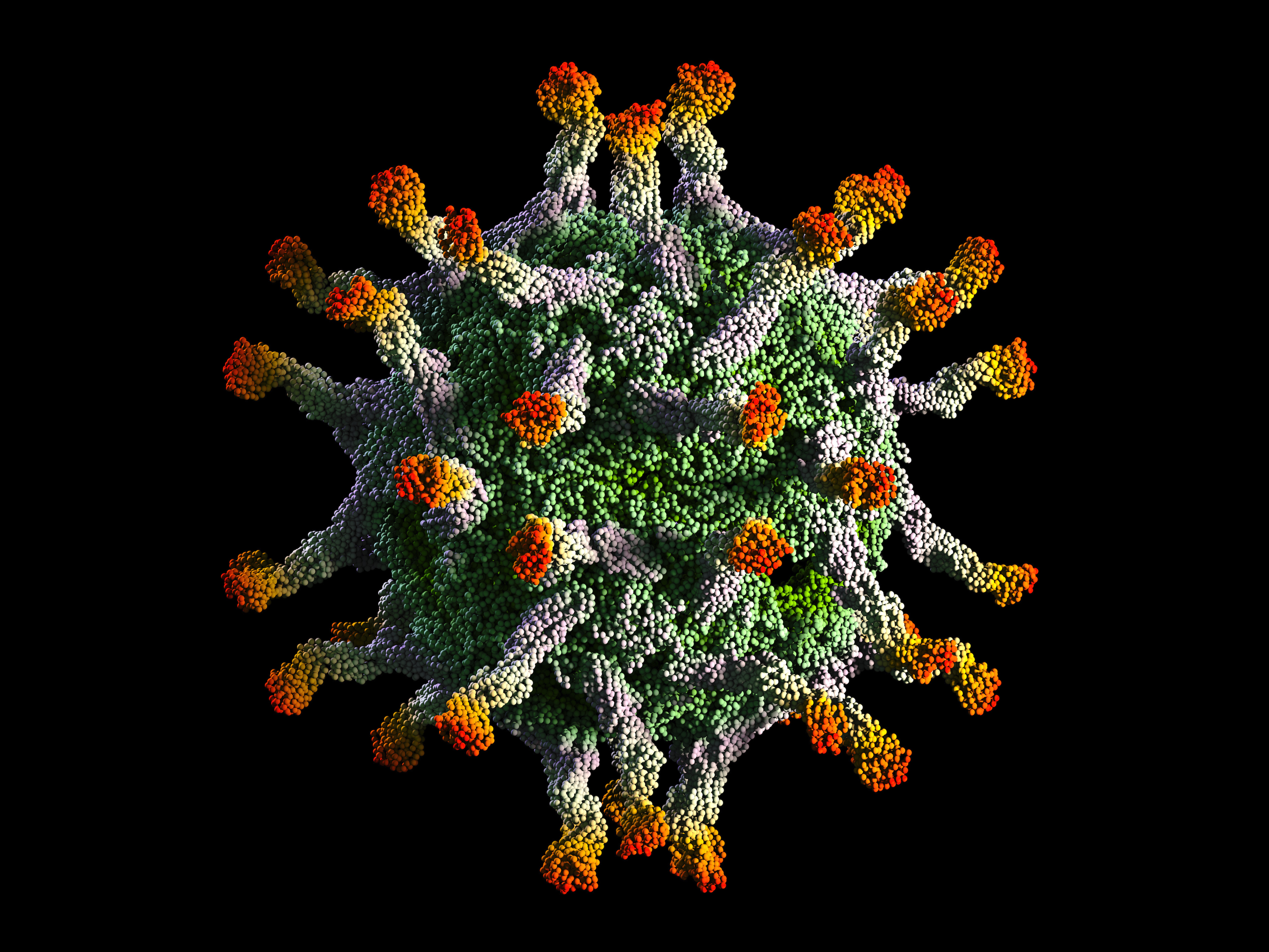

Banner: A model of the polio virus/Getty Images