Business & Economics

What we can expect from the 2023 economic ‘misery index’

Many Australians are struggling to pay for everyday essentials, but some of us are feeling the pinch more than others

Published 15 December 2023

As we head into the festive period, many Australians are facing a long-term cost-of-living crisis.

Thanks to inflation and incremental interest rate rises, more than half of us (around 56 per cent) are reportedly only just making ends meet – or actually failing to do so.

It’s also getting harder and harder for many of us to pay for essentials like food, bills, rents and mortgages. This level of financial stress is similar to what was reported during the pandemic – with 57 per cent of people struggling in 2020 and 55 per cent in 2021.

So, which groups of Australians are now finding it almost impossible to pay for necessities? And how can we encourage greater financial security?

These are some of the questions we have been exploring since the pandemic using the Taking the Pulse of the Nation (TTPN) Survey at the Melbourne Institute.

Business & Economics

What we can expect from the 2023 economic ‘misery index’

Since 2022, we have asked Australians about their ability to pay for essentials like food, energy, health and housing.

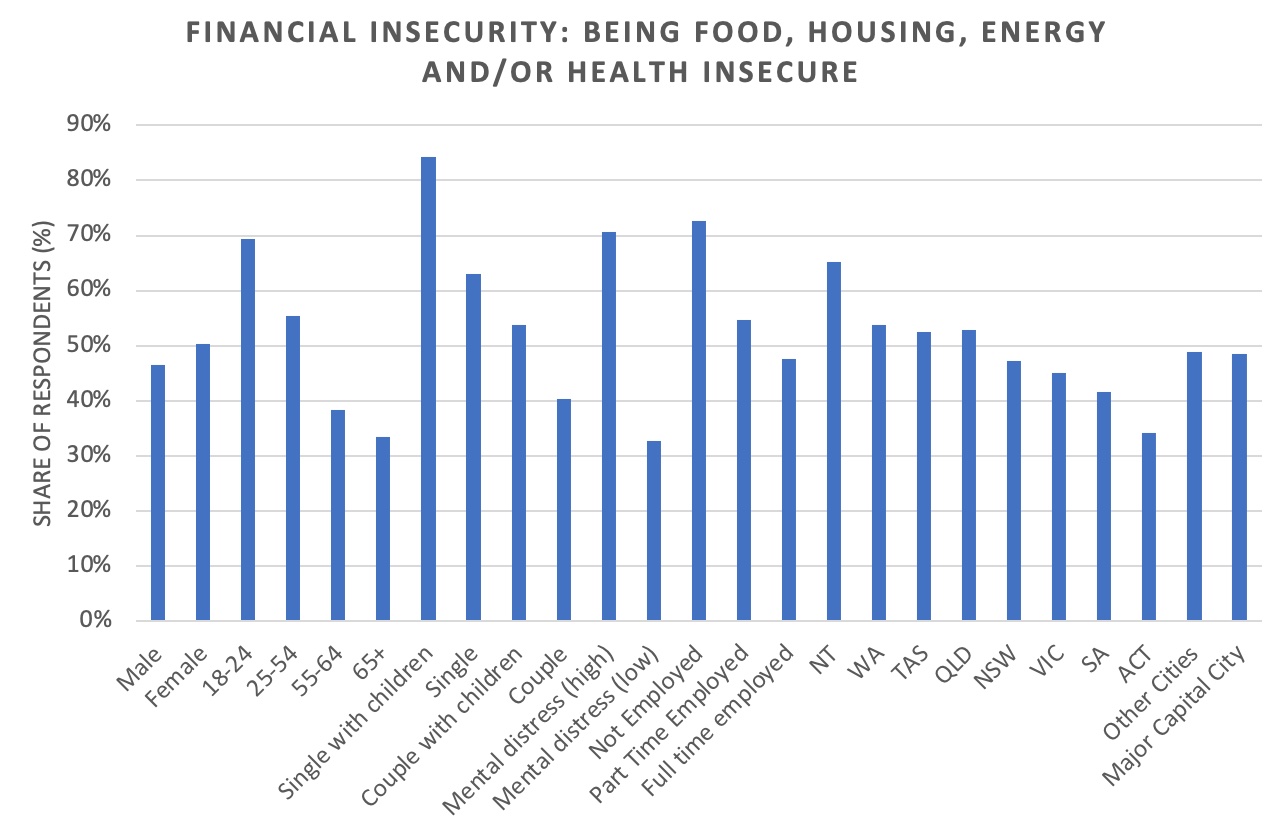

Our team measures financial insecurity as having one or more challenges in getting food on the table, paying for housing, covering utility bills or seeing a doctor.

Recently, we found the groups with the highest proportion of challenges include singles with children, young people aged 18 to 24, those with high levels of mental distress and people who are not fully employed.

Notably, 84 per cent of single parents face at least one financial challenge. We also found people in half of Australia’s states and territories are facing financial hardship – in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Tasmania and Queensland.

This has very real impacts for Australians and their families.

Take food insecurity, for example, which is reported by more than 60 per cent of those facing financial stress. There are three components that make up food insecurity – inadequate access to food, inadequate supply and the inappropriate use of food.

According to our research, women are more likely to report both eating less and skipping meals to save money (12.2 per cent for women and 8.6 per cent for men) – this is especially true of women aged 18 to 44 (around 19 per cent for women and 14.5 per cent for men).

In particular, single parents with children living at home are reporting high levels of food insecurity (over 40 per cent), followed by single respondents with no children at home (over 25 percent).

The youngest group (those aged 18-24) is more likely to be food insecure (more than 40 per cent of them) than the other people in the population.

In August, our research team expanded its questions to include a measurement of financial resilience. We asked Australians how they would cover an unexpected (emergency) expense of $AU3,000.

Our study found that, while 69 per cent of Australians would use their savings or assets to cover an unexpected bill of $AU3,000, nine per cent would not be able to cover the expense at all.

A further five per cent would work additional hours to try and pay the expense, nine per cent would borrow from the bank, and eight per cent would ask family, friends or the government for help.

Business & Economics

Avoiding the cliff and the freefall into poverty

When we broke this down by age group, we found young people in particular would struggle with an unexpected expense, with only 56 per cent of 18 to 24-year-olds reporting they could use savings compared with 74 per cent of people over the age of 55.

Being financially secure and having savings for an emergency are closely linked. People struggling to pay for food, housing, utility bills and/or health costs are also half as likely to be able to draw on savings or assets.

In particular, 45 per cent of people struggling with housing expenses and 20 per cent of people struggling with food or energy bills do not know how they would cover an unexpected expense.

And single parents with children are most likely to report not knowing how they would cover an unexpected cost or having to ask family or friends to borrow money.

On top of this stress, finding external sources of funding – like taking out a loan – may not be an option for many single-parent families. Once people are financially vulnerable, it becomes harder and harder to recover from these financial shocks and it becomes a cycle of disadvantage.

Financial insecurity is not just a short-term problem. Cost-of-living pressures shape major life decisions like choosing a house or career – and even whether to have children or not.

These pressures often compound to reinforce intergenerational poverty, making it harder for people to change their circumstances and reach a point of financial resilience.

For instance, Australian-born respondents perceive bigger financial barriers to higher education than foreign-born respondents (2.57 compared to 2.17), despite the financial support programs in Australia.

Politics & Society

Universities can’t forget about lower socio-economic students

Education is a key driver of intergenerational social mobility. If the perceived high cost of university deters impoverished Australians from attending, they may be missing out on the opportunity to break the cycle of disadvantage.

And, for some families, simply entering parenthood means raising their children in poverty.

Becoming a parent is associated with a substantial decrease in family income. We recently examined this ‘income penalty’ for the years 2001 to 2021 in Australia using HILDA Survey data.

We found that the arrival of a first child reduces household disposable income by an average of 23.3 per cent for one-parent households and 16.5 per cent for two-parent households.

This income penalty is associated with 63 to 70 per cent of one-parent households and 34 to 36 per cent of two-parent households remaining in or entering poverty within five years of having their first child.

Once parents (especially single parents) find themselves in poverty, it is very difficult to get out; high day-to-day expenses, limited available time for work and inevitable unexpected costs can trap people in a cycle of financial insecurity.

And this situation gets worse in a cost-of-living crisis.

Business & Economics

Persistent poverty is a major policy issue

Addressing the crisis should be Australia’s top priority, as stated by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the Economic and Social Outlook 2023 conference.

It requires policies and services, as well as encouraging people to think not just about making ends meet today, but how to save for that rainy day.

Elaborate government programs may not be the best solution for Australians in the early stages of financial insecurity.

Instead, providing information, supporting people to nip emerging challenges in the bud, and/or providing immediate solutions (like supplying grocery vouchers for people facing food insecurity) can help stop the spiral into poverty.

So while many of us struggle with the very real impacts of the cost-of-living crisis, it’s time for governments and service providers to work together to reduce the number of people who are being left vulnerable to falling into poverty.

Banner: Getty Images