Health & Medicine

A love letter to modern medicine

CPR training, publicly available defibrillators and a willingness to help are vital to improve the chance of survival after a cardiac arrest

Published 26 May 2025

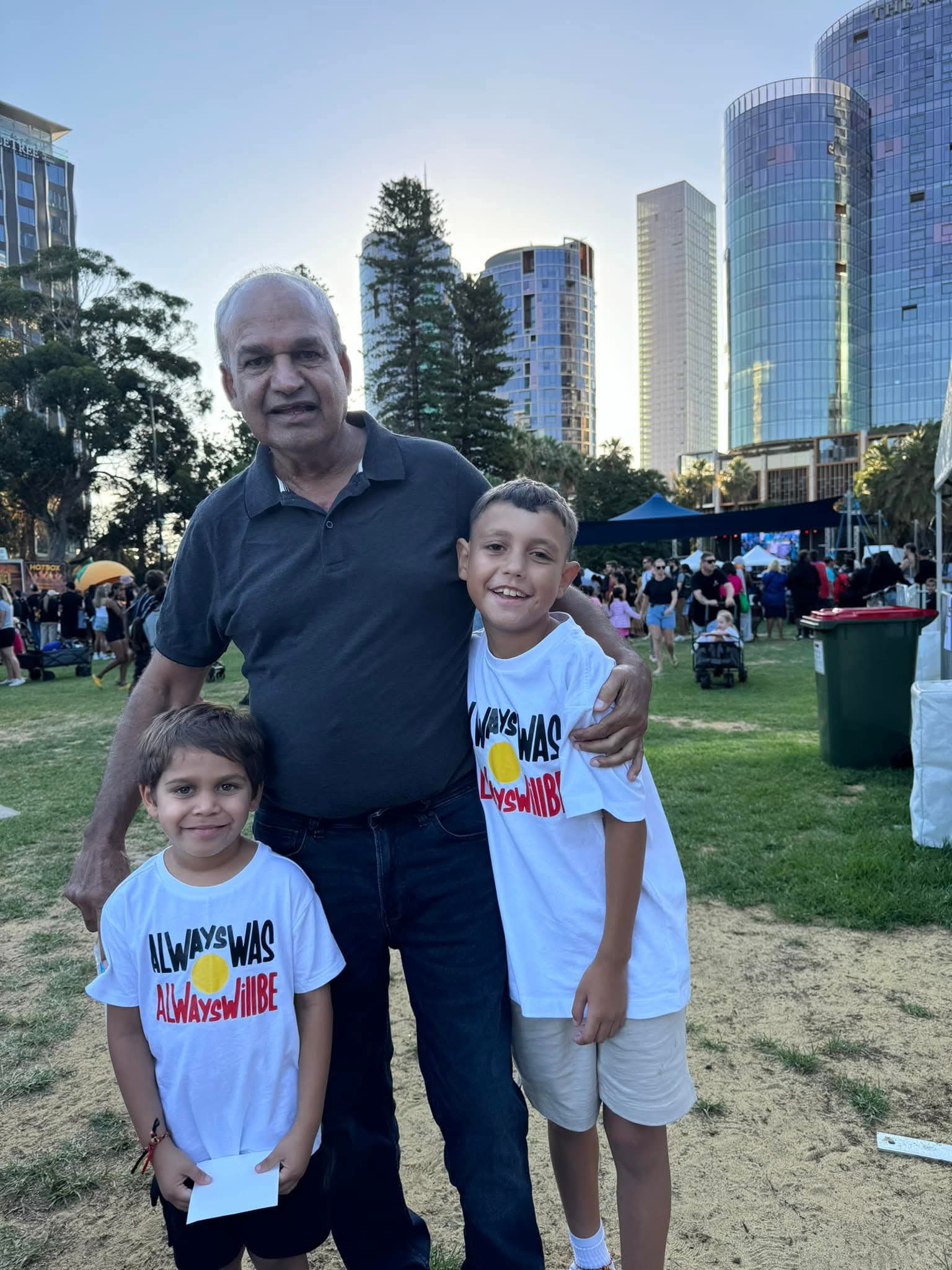

My brother, a 60-year-old Aboriginal man, recently had a heart attack in a public park on a sunny Sunday whilst celebrating the birthday of his three-year-old granddaughter.

He went into cardiac arrest.

He was surrounded by family when he began to feel himself blacking out. He reached out and grasped a nearby pole and slid slowly to the ground.

His adult children rushed over to check if he was OK. They found he had no heartbeat and was not breathing.

Six months on, he is alive and has recovered and that’s why I’m telling this story, because I want to challenge people to get trained and to be prepared to help if they witness a cardiac arrest.

When my brother collapsed, the likelihood of death was high.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest is a leading cause of death in young and middle-aged people, surpassing road accidents, cancer, and infectious diseases.

Nine out of ten people who have a cardiac arrest outside of a hospital die. For those who are lucky enough to survive, there is the added prospect of brain damage.

My brother had no history of heart disease and his blood pressure and cholesterol were normal when recently reviewed by his GP.

My brother is one of the lucky ones. He survived a cardiac arrest and was intubated and stabilised in intensive care. I flew from Melbourne to Perth early the next day to be with my family.

Health & Medicine

A love letter to modern medicine

To try to understand what had happened, I spoke with my niece, who was with her dad when he had the arrest. Although she has never been to university and has no formal first aid training, she led the immediate response when she saw her dad collapse.

Her story was so stunning that I asked if I could video record her re-telling the story on my phone.

While her sister was on the phone calling triple-0, she began providing first aid to her dad.

She began her story by saying, “I knew what to do from watching one of my favourite TV shows, Gray’s Anatomy. I knew that I needed to remain calm and begin compressing Dad’s chest.”

She was afraid to do mouth-to-mouth, so she yelled at a man standing by and told him to blow into her dad’s mouth and he did so at regular intervals.

After a while she said she tired and was unable to continue chest compressions, so her 22-year-old son, who also had no formal first aid training, took over chest compressions.

When he was tired, the man doing mouth-to-mouth took over chest compressions and continued mouth-to-mouth.

At this point my niece said a woman standing watching told her, “There is a defibrillator on the wall over there.” My niece said she ran approximately 100 to 200 metres to it.

It was locked and she had to call 000 to get the code to open the box – the first two codes the operator gave her failed to open the box, but the third worked.

She ran with the defibrillator in hand but began to find it difficult to breath – an asthma attack. Her son ran to help and she threw the defibrillator at him – he caught it and ran the remaining distance back to her father.

Neither my niece nor her son knew how to use the defibrillator, but some bystanders helped, using it twice on my brother. The first time, she said, “There was no response and I don’t think it was charged enough because Dad didn’t move.”

The second time, as the woman using it yelled, “Stand clear! Stand clear!”, his arms, leg and whole body lifted off the ground and he took a deep breath of air.

This was about five minutes after his heart stopped.

Business & Economics

How a First Nations’ approach in marketing is helping to decolonise healthcare

His heart seemed to be beating weakly, so they kept giving CPR, and when the police arrived they took over until the ambulance arrived about twenty minutes after he first collapsed.

When I arrived the next day my brother was in the intensive care unit at Fiona Stanley Hospital. He was still intubated and sedated, and during the day he was taken for an angiogram.

We had an intensive care specialist come to speak with my brother’s six adult children, my two sisters and me. She explained he had a moderate-sized heart attack and also had widespread coronary artery disease requiring surgery.

She also explained that when he awoke, we would know if he had any brain damage. To our great surprise he woke up with no sign of brain damage.

He remained in hospital and after 10 days had bypass surgery with four coronary artery bypass grafts.

Over recent months, while recovering from surgery, he began a cardiac rehabilitation program.

In the days that followed, as I visited him in the hospital, I thought more about his experience and my niece’s incredible story.

I knew that sadly most people don’t beat the odds and survive. As far as I could tell, multiple factors contributed to his survival:

People saw him go into cardiac arrest and acted immediately with treatment and called for an ambulance

He was in a public place with a defibrillator available for public to use

His daughter had some knowledge of what to do if someone had a cardiac arrest, even if it was from a TV show

Her son and passersby were willing to help her

The West Australian police were trained in first aid and took over providing CPR until the ambulance arrived

The ambulance arrived within twenty minutes and took over his care and transported him to a nearby tertiary hospital that was well-staffed and ready to respond to his situation

Finally, my brother believes his survival was a miracle – and I have to accept that even with all those factors working in his favour, there was a huge amount of luck that not everyone experiences.

We are all enormously grateful.

I am Chief Medical Advisor in First Nations heart health for the National Heart Foundation and I have dedicated my research to the study of how best to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus in young Indigenous people.

I have learned from this experience that CPR training for everyone is critical to helping improve survival.

The widespread availability of defibrillators in public places is an essential public health measure that saves lives – and they are safe to use.

While many Australians might be afraid of using a defibrillator or unsure how to use it, it’s much easier than you think. There are audible instructions and it does most of the work for you.

If a defibrillator is applied within the first couple of minutes, survival can reach as high as 70 per cent.

So, my message is this. If you have not completed a first aid course in recent years, whatever your background, it’s important.

You may never know when you might help save the life of a relative or a stranger.

It feels good to know that other Australians will step in and help provide lifesaving help in an emergency. My brother is alive because of it.

Hear Stafford Eades recount his experience on ABC Life Matters.