Health & Medicine

Dispelling the myths about transgender people

Around the world, trans people are under attack. So, while Transgender Day of Visibility is a celebration, we need to talk about the dread as well

Published 27 March 2025

Like many trans people, I view Transgender Day of Visibility with equal parts joy and dread.

For me, there are many aspects to the joy. I’m proud that I had the courage to overcome a lifetime of confusion and shame – finally admitting that I am trans.

I’m humbled by the strength and diversity of the community I have joined as a result.

Mostly, though, I’m just relieved.

Out of all the times in history and places in the world I could have been born, I live here. I live now. Because of this, I was able to transition from female to male.

I no longer carry the impossible burden of needing to lie constantly about a fundamental part of who I am. It is, truly, a gift beyond price.

Our joy is often the focus of Transgender Day of Visibility, and rightly so – it matters.

Health & Medicine

Dispelling the myths about transgender people

But I want to take this opportunity to draw your attention to the other emotions of the day, the ones we don’t talk about as much.

The dread. The fear. Because those matter too, and they are especially acute this year.

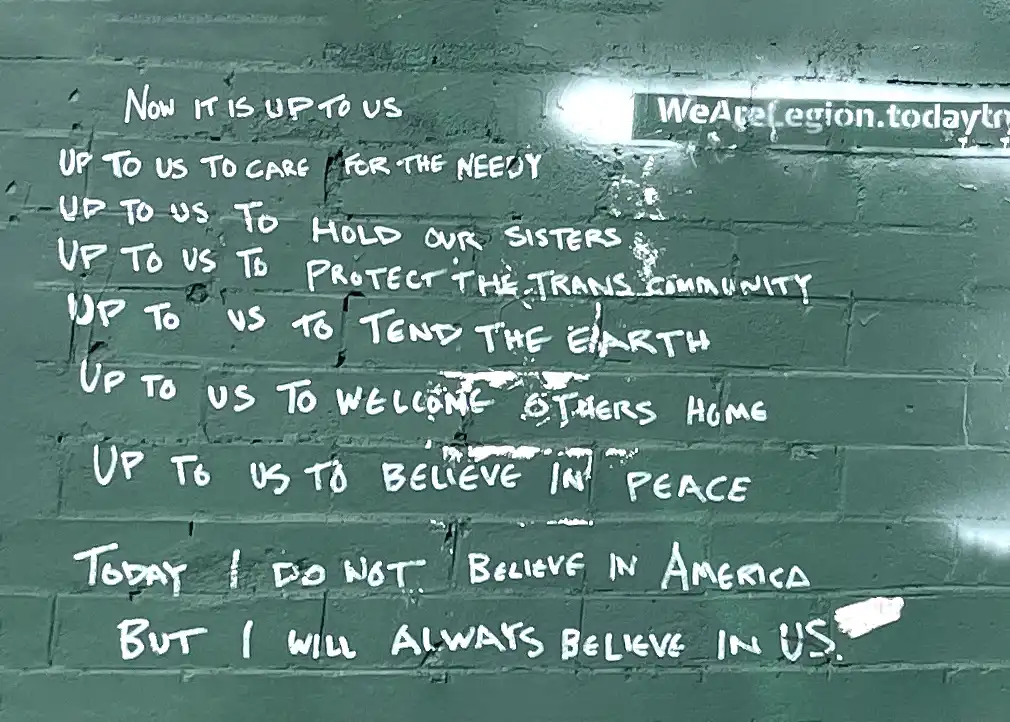

Around the world, trans people are under attack. The forefront of this is in the US with the election of Donald Trump.

In just the last few months, there have been laws banning trans people from using public restrooms and change facilities around the country; an executive order removing trans people from the military; an attempt to make it a criminal offence for teachers to support trans students by using their correct pronouns; a bill charging parents who support their trans children with child abuse; the reversal of gender markers on documentation like passports; a ban on participation in sport; the withdrawal of federal benefits and stripping of civil rights protections; a gutting of support for trans health care; an information and data purge of trans people from websites and documentation, with a possible end goal of denationalisation.

This is much worse than previous years, but only in degree, not kind. The US is the vanguard, but the trend is global.

Australia is not immune. We are already feeling some direct spillover from what is happening in America.

It is no longer safe (or possibly even legal) for trans people to travel to the US. Scientists here in Australia who share grants with people in the US have been called to renounce researching ‘woke’ topics like trans health lest we lose funding; many already have.

Much existing scientific research was based in the US and has already been discontinued, which will have global repercussions.

Moreover, the success of Trump has normalised anti-trans attitudes across the world, emboldening people within Australia who have similar political goals.

Health & Medicine

Challenging five years of transphobia

In January, the Queensland government banned puberty blockers for minors, which directly opposes the scientific consensus about best practice treatment for gender dysphoria.

We fear that this may be a harbinger of more to come. Australia has a habit of importing culture wars from the US and the UK.

My dread on this Transgender Day of Visibility comes not just because all of this is happening in the first place – which is bad enough – but because our visibility is itself often used as a weapon in a culture war that we are involuntary participants in.

Our visibility, like our persons, is both a target and a tool in a persistent anti-trans disinformation campaign that has spanned over a decade. I will go into this in detail in the next article in this series.

There is “nothing organic nor grassroots about this”, but both the campaign’s nature and its relentlessness are nearly completely invisible to outsiders.

Fundamentally, this campaign seeks to manipulate emotions, setting trans people up as scapegoats onto which people can direct uncomfortable feelings that they do not know how to handle.

When women worry about their safety in public bathrooms despite the fact that there is no evidence that trans people pose any danger whatsoever, I wonder – is this really about us, or is it actually a fear of being powerless and vulnerable to men in general?

When people rail angrily about pronouns and extremist overreaching that they have never experienced themselves in real life, I wonder – is this really about us, or is it actually rage about feeling left behind in an increasingly stressful and changing world?

When parents worry about their children being brainwashed by “ideology” despite the fact that there is no evidence for this and trans kids thrive when they are affirmed, I wonder – is this really about us, or does it reflect things like their own unease around gender, or their own anxieties about losing centrality in their kids’ lives?

Health & Medicine

Why are we so vulnerable to bad information?

I’m not blaming people for having complicated feelings. We all do.

But that doesn’t mean the feelings are correct.

Emotions are important signals of what matters to us, but their strength is in their power rather than their specificity or accuracy. This means that even when we succeed in identifying what we are feeling, we often find it difficult to understand why.

An emotion can be very strong and very genuinely felt, even when the explanation assigned to it is 100 per cent wrong.

Indeed, there are strong psychological motivations for people to create and believe in wrong explanations.

We have layers of defence mechanisms, built up over a lifetime, aimed at doing this. Therapists and psychologists exist at all because it is so important, and so difficult, to tease these layers apart on our own.

This is all very depressing.

I don’t write to instil you with dread. Our world has enough of that to go around and it is a real act of resistance to embrace joy instead.

And, truly, despite everything, I have a lot of joy.

One source of hope is the fact that I know that people do extraordinary things if they have the tools they need.

With this article (and the next one in the series), I aim to give you a tool: an understanding of what is happening now.

I am asking you to do the following extraordinary thing: remember and apply this knowledge.

I am proud and honoured to be visible to you on this day.

This article was updated on 18 April 2025.