Health & Medicine

Filling in the genetic blanks of breast cancer predisposition

Researchers have discovered a new type of immune cell that helps keep breast tissue healthy within mammary ducts – the sites where milk is produced and transported – and where breast cancers arise

Published 28 April 2020

While it’s usually used in a military or sporting context, the saying ‘the best form of defence, is often attack’, also applies to our immune system.

Like all good armies, particular immune cells survey their surroundings, destroying our body’s cells that have been invaded by bacteria or viruses, and those that are damaged or dying.

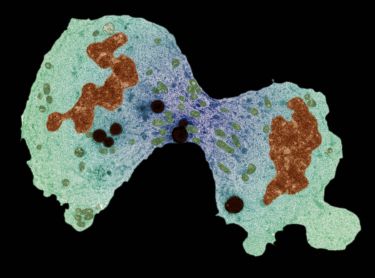

Appropriately, these cells are called macrophages, coming from the Greek words ‘big and eater’. Most organs including the brain, liver, lung, skin and intestine, have their own macrophages that play very specific and important roles in function, disease and repair.

For the first time scientists have now found a unique type of macrophage that lives inside mammary ducts, the structures where milk is produced and transported, but also where breast cancers arise.

Health & Medicine

Filling in the genetic blanks of breast cancer predisposition

The research was led by Walter and Eliza Hall Institute researchers Dr Caleb Dawson, Professor Geoff Lindeman and Professor Jane Visvader, along with Dr Anne Rios who is now based at the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology, Netherlands, and is published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

“Because they live within the mammary ducts, we have called them ductal macrophages, or ‘DMs’,” says Dr Dawson.

“Shaped like tiny stars, these macrophages form a network that covers mammary ducts. They don’t move around the ducts, but each cell has many tiny arms that it uses to monitor the ducts and protect them from damage,” he says.

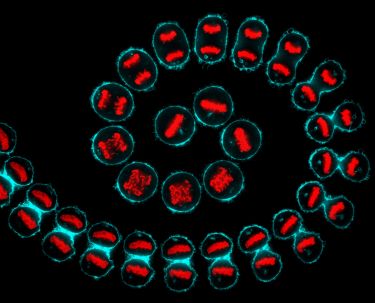

The mammary gland is a dynamic organ that undergoes dramatic remodelling throughout puberty, pregnancy, breastfeeding and back again to a resting state. The branching ducts bloom into milk-producing ‘factories’ during lactation, which must be eliminated once a baby weans.

DM cells play an essential role at a pivotal point in mammary gland function called involution when lactation stops, milk-producing cells die and breast tissue needs to remodel back to its original, resting state. This is an impressive feat, as milk-producing cells are huge in comparison, containing twice the normal amount of DNA.

Mammary ducts are of particular interest to breast cancer researchers because this site is prone to cancer development, so understanding how these immune cells function in healthy development could lead to important new insights for treating breast cancer.

“We were taking 3D microscopic images of breast tissue to see how different types of cells interact with the ducts of the mammary gland,” Dr Dawson says.

Health & Medicine

Putting cancer cells to sleep

When we imaged immune cells, we were shocked to notice that there were some within the ducts, squeezed in between two layers of the mammary duct wall,” he says.

“We first looked at their behaviour by filming them in mouse mammary tissue, which hadn’t been achieved before in such great detail. We saw that DMs were waiting on top of the milk-producing cells monitoring for damage, and as soon as they died, the DM’s ate them.”

When the researchers later removed ductal macrophages from the mammary ducts they discovered that no other immune cells were able to swiftly carry out this essential process.

Dr Dawson says the discovery provides a great step forward in our understanding of mammary gland biology and how completely different cell-types – immune and duct cells – can cooperate.

The study also filled in a missing piece of the puzzle of breast cancer development.

More than 19,000 Australians are diagnosed with breast cancer every year. It is the most common cancer in Australian women.

Dr Dawson explains that although DMs are important for keeping breast tissue healthy, this might not be good when they keep doing this in breast cancer.

Health & Medicine

Our cancer preventing genes revealed

“We noticed a strong similarity between DMs and breast cancer macrophages that aid tumour progression and metastasis or spread. Their similarity suggests that the pro-cancer activity of macrophages might be related to their function within normal mammary ducts, such as helping with remodelling” Dr Dawson says.

Some tumours are able to protect themselves by manipulating macrophages – hijacking them into helping cancer spread.

“Ductal macrophages are spread throughout the mammary ducts. As cancer grows, these macrophages also increase in number,” Dr Dawson says.

“We suspect that there’s the potential for ductal macrophages to inadvertently dampen the body’s immune response to cancer. This would have dangerous implications for the growth and spread of cancer in these already prone sites and would affect cancer treatments.”

“Our next steps are to explore the function of ductal macrophages at different stages of mammary gland development, such as the transitions into adulthood and pregnancy. We also want to investigate the role that these duct-specific immune cells play in helping cancer to grow and spread,” he says.

Professor Visvader says discovering mammary duct-specific macrophages was a remarkable step forward in understanding how the immune system interacted with the ductal network and impacted upon mammary gland development.

“The team’s ultimate goal is to understand these cells enough to manipulate them,” Professor Visvader says.

“Given that tumour macrophages likely promote growth of the tumour, blocking their activity could serve as a treatment strategy for breast cancer.”

The research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the National Breast Cancer Foundation, the Australian Cancer Research Foundation, The Qualtrough Cancer Research Fund, Cure Cancer Australia and the Victorian Government.

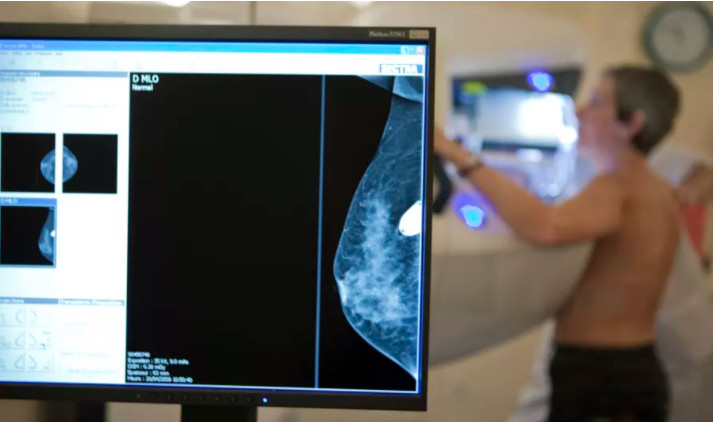

Banner: Dying breast cells captured during the process of involution. Dr Caleb Dawson/Walter and Eliza Hall Institute