Health & Medicine

From hunting to contracting

Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi man Stan Grant reflects on the limitations of racial identity, and the unprecedented numbers of Indigenous Australians taking their places in the modern economy

Published 8 December 2016

My paternal grandfather, Cecil Grant, was a man born in the first decade of the 20th century onto the fringes of the frontier, a man whose life embodies the shift of Aboriginal people from outcasts on the edges of society, to take up a place in Australia.

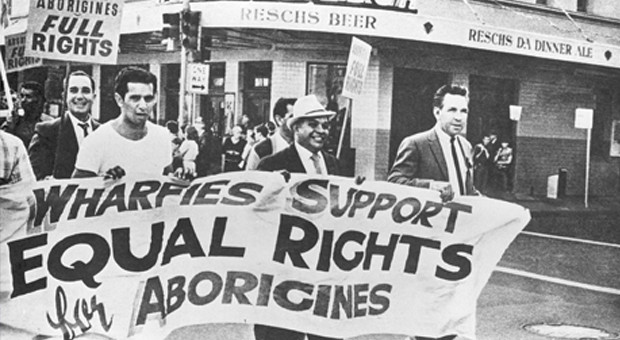

He was at times a shearer, a rodeo bull rider, a rabbit trapper, a fruit picker and soldier – his personal journey in the black migration from mission to town a distance of mere miles, but an epochal trek. He was a friend of Doug Nicholls and another seminal Aboriginal leader, Bill Ferguson, and had campaigned with them for citizenship rights as well.

In 1966, a year before the most successful referendum in Australia’s history that endorsed Aboriginal people to be fully counted in the national census, he stood for election as the Aboriginal representative of the Aborigines Welfare Board, a body that exercised an often-fearsome control over black lives. I found my grandfather’s campaign pitch, along with those of other candidates, in an edition of the Aboriginal Welfare Board’s newsletter Dawn, a magazine that was distributed to Aboriginal people throughout New South Wales.

It is an extraordinary time capsule. It takes us back to hear the voices of Aboriginal people and what they were aspiring to. Most of them speak of their Christianity and economic empowerment. They call for fishing and economic cooperatives, for Aboriginal reserves to be turned into farms. As one wrote: “if we can work farms for white men, we can do it for ourselves.” They talk of their people needing to shoulder responsibility for their plight, and don’t we hear that echoed today. All of the men stressed their work ethic, and desire to find a place in modern Australia.

As one says: “I’ve held numerous jobs from farmhand, fisherman, mill hand, factory worker, sewerage ganger, miner, to my present position and according to all reports, I am accepted everywhere.”

Health & Medicine

From hunting to contracting

These are the powerful voices of the Aboriginal economic migration.

These people emerged from the missions, lives bound and controlled, to demand a seat at the table. They are people with a straight-backed dignity, and unstinting in their demand for their rights. The people of my grandfather’s generation saw an open door, and they marched through it.

They didn’t just demand equality. They assumed it.

When I see them, I see individuals with choice, shaped by their world, as they in turn shaped the world around them. They were alive to the possibilities of life in an Australia whose economy was often booming.

They looked at the post-war migrant influx and hitched a ride, becoming economic migrants themselves. The meagre pay and menial work didn’t dissuade them, as by their own admission they (often in desperation) fought to provide for their families. A dynamic and diverse Aboriginal population was emerging from these people in transition.

A decade ago the late academic, Maria Lane, probed this migration and the world it has created. She observed two diverging Indigenous populations. An Aboriginal woman, Lane was drawn to the emergence of a fledgling open society, as she called it. It was opportunity, effort and outcome oriented, contrasting with what she called an embedded society, which was risk averse, welfare and security-oriented.

The two populations, she said, are linked through kinship and continuing interaction, but the course of their lives was set by the great Aboriginal economic migration. It was a slow grind, but, she said, a new paradigm was slowly but surely emerging. These were the people on the move in the 1940s to the 1970s, leaving the settlements and throwing off the heavy hand of government control. Their journeys I’ve already traced through my family. The timing was crucial. Their movement coincided with periods of economic growth that increased their opportunity.

As Lane said, it was a risky move into the unknown. But one that for most, paid off, just as it did for other economic migrants, drawn from the far-flung corners of the earth.

Lane picked up their story when the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these pioneers were exploding into higher education. She focussed on South Australia and found that in less than a decade from the late 90s to the mid-2000s the number of Indigenous students entering the last year of high school doubled, and of those, the number gaining good university entrance scores had likely tripled.

These kids, Lane says, were part of both white and black worlds, redefining what that meant for them.

At the same time, she’s pointed out, there was a parallel Aboriginal universe, an embedded shadow world of choking poverty, rivers of grog, frightening rates of violence, overcrowded housing and intergenerational unemployment.

While the children of Lane’s open society were graduating high school, their embedded society cousins were committing suicide at rates 10 times higher than the rest of the Australian population. They were graduating, not from high school, but from juvenile detention to adult prisons.

In the embedded society were those who were left behind. Maria Lane mapped their journey too. Many have never left the settlements. Many had ventured into small towns and had then returned. Many had simply missed the economic cycle and failed to grasp the full range of opportunities. Instead they became locked in cycles of welfare dependency and social decay at a time when government policy was making it easier to sit down. They became embedded. But no broad social sketch can be entirely accurate. Individuals are too unpredictable and there is a risk sometimes of caricature and stereotype.

There is great community and enduring bonds of family found in Lane’s embedded society. I know these people. This is also my family. I know that they can be generous, loving and loyal, and life in the open society for us can be lonely, alienating. Even the most successful Indigenous peoples are not immune from random or hurtful racism. Lane sometimes is guilty of ascribing too much of the fate of these two populations to the vagaries of personal choice, when in fact history, economy, timing and luck have often been far more decisive.

Yet she did identify a schism in our population, and it punctures the lazy and convenient assumption of just an homogenous Aboriginal society, where we are all the same.

Between 1996 and 2006 the Indigenous community in Australia was transformed. Numbers of educated well-paid professionals exploded. In just a decade, they increased by nearly 75 per cent. That was more than double the increase in the non-Indigenous middle class. By 2006 more than 14,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders between the ages of 20 and 64 were employed in professional occupations. That’s 13 per cent of the total Indigenous workforce.

Dr Julie Lahn, from the Australian National University, looked at this phenomenon in her paper called Aboriginal Professionals: Work, Class and Culture. She said that Aboriginal professionals in urban centres remain largely overlooked. Dr Lahn thought this was a major shortcoming that impedes a fuller understanding of the processes of transformation which are increasingly evident to Aboriginal people themselves. We see this in our universities. There are around 30,000 Indigenous university graduates in Australia. In 1991 there were fewer than 4000.

Arts & Culture

We are the Australians, we have the power

That number is likely to double in the decade to come. We are now in an era where we are seeing a second generation of Indigenous PhDs. Now the emergence of this middle class, of which I am assuredly a part, presents new questions for identity.

That I am an Indigenous person is a fact of birth. That is who I am, but that is not all I am. The reality is more ambiguous, it defies easy definition, even as I may try to cloak it in a veil of certainty. To borrow from Franz Kafka, identity can be a cage in search of a bird.

I was born into that half-caste community that emerged from the Australian frontier; a hybrid society formed out of the clash of old and new. In that society they married each other, repopulated in the harsh segregated settlements designed to Christianise, civilise us and smooth the dying pillow.

Being an outsider, something other, sits more simply with our history of exclusion and injustice. My family has suffered through generations, lived at the coalface of bigotry and poverty. I was born into a life on the margins. As I have written in Talking To My Country, we lived in Australia and Australia was for other people.

But I have grown from the boy that I was, and my country has grown from the land that it was. Can I truly see privilege as white? Is it black to suffer crippling disadvantage? If these things are true, then I’m assuredly white.

I am an Australian with all the privilege that that brings. Am I a coconut? We know that term. That’s the putdown Indigenous people use for those suspected of trying to pass. It means being brown on the outside and white on the inside. It’s meant to hurt. But to me, it says more about the person levelling the insult than its intended victim.

It isn’t surprising. Aboriginal people have historically been defined and redefined in and out of existence.

The Australian Law Reform Commission counts, since settlement, 64 separate categories of Aboriginal. For Aboriginal people, resolving who is Aboriginal and who is not is an uneasy issue, located somewhere between the individual and the state.

Some Indigenous people have begun to explore the impact of this Aboriginal middle class. They recognise it as a phenomenon that is met with suspicion, even hostility, by some in the Indigenous community.

Larissa Behrendt in an article for The Guardian, Who is Afraid of the Indigenous Middle Class sees a fracture in Aboriginal communities and politics between an old guard forged in anger and loyal to the power of protest, and a new generation seeking to work within the system, to join the professions, participate in party politics and seek to make a change.

As she wrote, the fracture seems reflective of so many divisions in Indigenous politics, from opinions about constitutional recognition to disagreements about the nature of welfare reform. While almost everyone can agree on the problems, she writes, the solution causes deep ruptures.

Larissa Behrendt bells the cat when it comes to the hard questions posed by the new form of Indigenous success. How does a community that has partly been defined by its exclusion, disadvantage and poverty, redefine itself? How does it increase its participation in the mainstream and not be assimilated?

Behrendt ultimately argues that a person’s cultural identity should not be tied to poverty. You are not more Aboriginal if you are struggling. But still, suspicion remains. The members of this black middle class are just as likely to be viewed as coconuts.

In her series of Boyer Lectures, Marcia Langton tied the growth of an Indigenous middle class to the Australian mining boom of the early 2000s. She conceded that she had to confront the old trope of Aboriginal people as the hapless victims of a voracious and brutal mining industry. Now it is beyond trite to suggest that a university degree and a job means that someone is no longer or less Indigenous. Identity should not be means tested. We are free to define ourselves and what being Indigenous means. The new black middle class is developing its own consciousness.

Some reject the idea of class identity, preferring to cling to ideas of race, referring to themselves as ‘just black fellas’. But others are embracing a cosmopolitan identity beyond the mob. Indigenous Australia today is a complex, diverse organism. It is lacerated by class, gender and geography. Individuals seek to express themselves, apart from their communities. In this way, we are no different to other peoples.

Arts & Culture

Womin Jeka: A choir with the desire to inspire

I’ve been inspired by the works of philosophers Amartya Sen and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Sen warns of the dangers of what he calls exclusive, “solitarist” identities that are formed around division. He believes this makes our world inflammable.

As a reporter, who has spent three decades walking the fault lines and the trip wires of global geopolitics, seeing up close how age-old enmity and the politics of identity can pit Catholic against Protestant, Sunni against Shia, Hutu against Tutsi, Muslim against Hindu, I can only concur with him.

Appiah counsels us to look beyond our parochial ideas to a shared sense of ourselves. Difference is to be celebrated, culture and kin and community cherished. But we should remain open to all of life’s rich tapestry.

His philosophy is captured in the words of the playwright Terence, a man bought and sold as a slave in Ancient Rome, whose words speak to us from when he wrote them more than a century before the birth of Christ.

Famously he wrote, Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto / “I am human and nothing of that which is human is alien to me”.

This is the lesson I draw from my ancestors.

From the earliest days of settlement, they grasped their futures in this new world. A world that brought devastation, a world they met with fierce resistance and accommodation. They found a new place in the new economy, economic migrants in the land of their ancestors. I am of these people. I am everything that they have made.

I was the boy who spent his young years moving from town to town, a life lived peering through a car window, as my parents looked for work. I was a part of the great migration. The descendants of these pioneers are today ... the new generation of doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers, scientists and economists. They are plumbers and carpenters and electricians and builders. They run small businesses. They are entrepreneurs and they are redefining what it is to be an Indigenous person. They overwhelmingly live in our cities and large towns.

The heritage is drawn overwhelmingly from black and white. They are married to Chinese, Italian, Greek and Lebanese. In this way, they form part of the mosaic of 21st century Australia. They are reviving their ancestral languages and cultures, as they also speak French or Arabic or Mandarin. They find congregation in the many faiths of this nation, counting among their number Indigenous people who are Jews, Christians, Buddhists and Muslims.

The renowned Australian anthropologist WEH Stanner once remarked that for Indigenous people the dreaming and the market are mutually exclusive. For Stanner the market was everywhere, and Indigenous people fixed in time and place.

But this is not true of any people, anywhere. Culture is not static. Identity is fluid. Our ancestors’ genius for adaptation and discovery brought them here away back in the deepest mists of time. They made the first open sea journey in the history of humanity.

They survived and forged an ongoing and unique culture in an isolated and largely inhospitable land. They met the rupture of the coming of the British, and the dispossession, with courage and resilience.

And yet, today we are reminded that life for far too many Indigenous people is hard, very hard. We measure this in statistics that tell us that that first peoples are overwhelmingly imprisoned, doomed to short and impoverished lives. Children not in their teens are committing suicide, their mothers more than 30 times more likely to be the victims of domestic violence, many dying at the hands of men who should love them.

Teenage boys scream to us in lonely cells with hoods on their heads. Here is the blight on the Australian dream.

The solution to these challenges are complex and often contradictory. But when I hear the voices of our past, when I look again on the extraordinary achievements of our forebears, I know one thing. Those who can walk in our world empowered, can prosper. They can stand in the dreaming, and in the market.

This is an edited extract of journalist Stan Grant’s 2016 Narrm Oration – the University’s key address that profiles leading Indigenous peoples from across the world in order to enrich our ideas about possible futures for Indigenous Australia.

Banner image: Stan Grant delivering the 2016 Narrm Oration at the University of Melbourne. Photo: Peter Casamento.