Politics & Society

More Jaw Jaw: Stopping North Korea going critical

North Korea’s latest missile test has graphically demonstrated how it’s prepared to play the strategic game against the United States

Published 29 August 2017

By firing a ballistic missile over Japan while the US and South Korea are engaged in joint military exercises, North Korea has provided an important insight into how strategic nuclear dynamics could likely play out on the Korean peninsula.

There now exists a very real prospect the nuclear crisis may spiral out of control. And Pyongyang may seek to deliberately cultivate just such a danger.

The ballistic missile that overflew Japan on 29 August is the Hwasong-12, an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile. We are fairly sure of this because the maximum altitude, about 550km, is similar to what one would expect of a Hwasong-12 fired on a standard minimum energy trajectory. The missile also flew 2,700km before breaking up into three parts. The Hwasong-12 has a maximum range of about 4,500km.

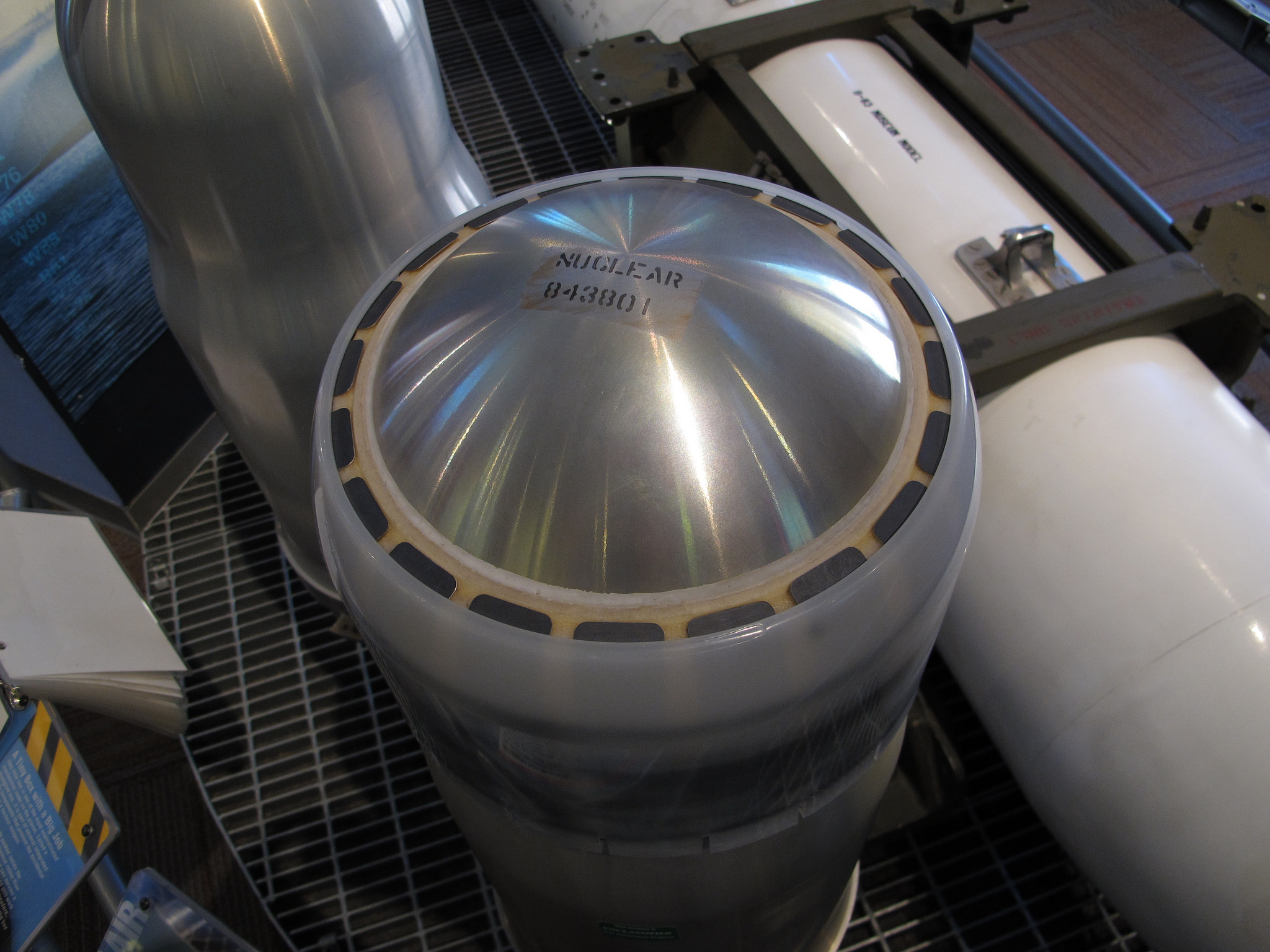

The Hwasong-12 forms the first stage of the two-part Hwasong-14 ICBM, which was successfully tested on 4 July and 28 July. Ballistic missiles with strategic nuclear payloads must be reliable, as well as being seen to be reliable, if they are to serve as credible nuclear deterrents.

The partial success of the latest Hwasong-12 test means we should expect more Hwasong-14 ICBM tests soon, perhaps also over Japan. This is because missiles tested on a standard trajectory provide more insight into the survivability of the re-entry vehicle – which protects the nuclear warhead from the rigours of re-entry into the atmosphere – compared with the highly-lofted trajectories that North Korea has used so far.

Politics & Society

More Jaw Jaw: Stopping North Korea going critical

Doubtless the North Koreans would have been disappointed that the Hwasong-12 broke up, as Pyongyang’s scientists could have learnt more regarding re-entry vehicle dynamics from a successful standard trajectory test.

Some commentators have speculated the Hwasong-12 and Hwasong-14 first stage are essentially powered by the Soviet-era RD-250 family of liquid-propellant engines – acquired through espionage from Ukraine.

But this is not accurate.

The first stage engine for both missiles has similarities with the RD-250, but some important features are not shared. They have some elements in common with early Chinese missile and rocket engines, and those which are shared with the RD-250 are more reflective of engineers hitting upon the same solutions to the same problems.

North Korea has developed its more advanced missile capabilities largely indigenously, and any assessment of the strategic situation on the Korean peninsula cannot be based on wishful thinking regarding the scientific capabilities of North Korea.

Those days have now passed. North Korea has, or is very close to having, the ability to fire a nuclear weapon at the US mainland.

The Hwasong-12 test of August 29, unlike any other, shows us how nuclear dynamics will work on the Korean peninsula. Theoretical analysis regarding the rational basis of nuclear deterrence suggests it can be made most credible via two means.

The first is through possession of overwhelming strategic firepower and flexible nuclear employment doctrines geared toward controlling escalation. This means that it is theoretically possible to limit damage to oneself, even when the nuclear threshold has been crossed – and this possibility makes deterrence credible because an opponent will always suffer more in any nuclear conflict.

North Korea does not have overwhelming strategic firepower. That is a quality Washington possesses.

However, the second route to credibility North Korea has in bucketloads. That second strategy is one known as “the threat that leaves something to chance”.

Politics & Society

Australia’s strategic steps before any North Korean conflict

North Korea, through its provocative actions, graphically demonstrates that in a crisis it would be quite prepared to manipulate external perceptions of risk. The Soviet Union and China were, and in the case of China remain, highly risk-averse nuclear powers.

But North Korea is showing that in a crisis it won’t be nearly as risk averse. The outcome of a crisis then essentially becomes a matter of chance. A game of Russian roulette.

This posture would conflict with a key US concern, namely the credibility of extended deterrence. Washington provides South Korea and Japan with a nuclear umbrella, but when the US itself becomes vulnerable that umbrella becomes less credible.

Would the US be prepared to give up Los Angeles and San Francisco for Seoul and Tokyo?

In a crisis, the US must demonstrate that its deterrent extended to Japan and South Korea is credible, and that means Washington must show, and be seen to show, resolve.

Putting Pyongyang’s “threat that leaves something to chance” and Washington’s concerns about the credibility of extended deterrence together in a crisis provides for an explosive mix potentially as potent as any critical mass of plutonium.

Business & Economics

We need one law for all

We should not simply accept a nuclear North Korea through a misplaced belief in the stability of nuclear deterrence, or the inadequacies of North Korea’s technical capabilities. Any military options – and there has never really been many – have by now become almost wholly irrational.

That means diplomacy is the best means to eliminate nuclear danger on the Korean peninsula, and recent statements from Pyongyang have suggested they are willing to discuss the denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula.

We should put North Korean diplomatic statements to the test before they test another missile or their first hydrogen bomb.

Banner: Getty Images