Now we know: Why we stand in queues

Queuing is governed as much by environmental design as unspoken rules promoting equality and efficiency

Published 15 January 2016

Queuing. It’s something we all do, whether we are waiting for a bus, our morning coffee or in the supermarket.

But how do we know when and where to form a queue? What rules do we obey and why are we so accustomed to waiting in line?

Professor Nick Haslam, from the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences at the University of Melbourne, describes queuing as a social norm, governed by unspoken rules promoting efficiency and equality.

“Queuing exists because there is an imbalance between the supply and demand of services,” he says. “If we could get the desired level of service when we wanted it, there wouldn’t be queues. But in a world where there is more demand than supply, queuing is a very efficient way to deliver a service without having a scrum of people fighting to get to it first.

“It also prevents people who are the loudest, the most devious, the most assertive or the biggest from gaining unfair advantage.”

With many services in constant demand, queuing is inevitable. In fact, Professor Haslam says most service providers actively encourage their customers to queue, all without saying a word.

Environmental design

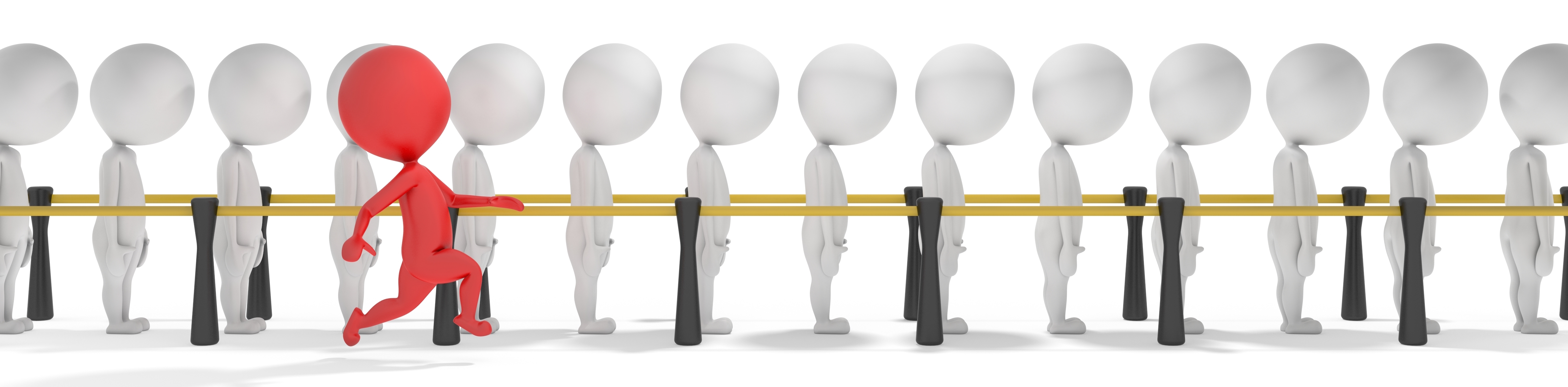

How do they achieve this? It all comes down to environmental design and, in many cases, the structured placement of retractable queue barriers.

“If you see one of those long, serpentine queues leading to the Qantas check-in counters, it is very clear that you are supposed to queue,” says Professor Haslam. “The environment is set up to imply queuing, and people are accustomed to following those expectations.”

But queuing is not always imposed on us. Groups of people will often self-organise while waiting.

“People usually choose to queue because it is fair,” Professor Haslam says. “In fact, queues are places where people are obsessed with fairness, and where cutting in line is seen as a terrible crime that can lead to all sorts of scuffles, fights and frictions.

“Ultimately, queuing defines a clear relationship between when you arrive and when you receive the service you need. People find that satisfying.

”While the need to queue depends largely on the activity, a person’s willingness to queue occurs in varying degrees around the world. Britons, in particular, are renowned for their orderly and regimented approach to queuing.

“The stereotype of the Anglophone countries is that queuing is something they specialise in,” says Professor Haslam. “The more charitable view is that there is a strong tradition of egalitarianism in many of these places – and the queue is a form of equality, where if you seek a service first, you are served first, regardless of your social position.”

But queuing also increases a person’s vigilance.

“If there are parallel queues, people tend to think the other queues are moving faster,” Professor Haslam adds. “We’re very, very alert. When you queue, the whole issue of fairness is so salient in your mind that you compare yourself implicitly to the people next to you. And people become quite unhappy if other queues move faster.”

Degrees of fairness

While our approach to queuing may seem inflexible, there are degrees of fairness – and Professor Haslam says it depends on the situation.

“In emergency rooms, for instance, we don’t expect orderly queues. People generally don’t mind being bumped by someone who comes in with a more severe condition than they have. So if you’re waiting to have a little cut on your hand treated, and someone comes in with a broken leg, we don’t mind violations of queuing order in those circumstances.”

How then do we react to queue-jumpers?

“In many cases, our response goes well beyond irritation,” says Professor Haslam. “Queue-jumping angers people because it violates equality and the norm that everyone else is obeying.”

Of course, some people are simply unaware of the local norms regarding queuing – an issue that Professor Haslam says can lead to intercultural tensions.

“You do sometimes find unfortunate situations where people get angry and moralistic with others who don’t know the local rules for queuing,” he says. “These people are not being devious or intentionally violating the local norms, they just don’t know them.”

In any case, Professor Haslam says learning the local rules on queuing is a challenge.

“You have to know that the rules exist, and you have to know when they apply,” he says. “That’s why in places where queues have to be regimented, like airports, you really don’t have a choice. But in places where people have to self-organise, it is always more tricky.

“The rules of queuing are simple to follow. Anyone can be a sheep and move along in the line.”

Banner Image: Shutterstock