Politics & Society

Disinformation damages democracy, but perhaps not in the way you think

Any new Australian government must navigate the confronting reality of a 'post-America Asia' as part of its foreign policy, but that’s not being talked about in this election campaign

Published 1 May 2025

Foreign policy is often marginal in Australian elections.

Yet, despite the understandable focus on rising egg prices and unaffordable housing in this year’s “cost-of-living election”, the outside world has loomed larger than usual.

An understanding of the USA and China has become central to any discussion of Australia’s future prosperity and security.

The chaos of the Trump administration’s all-out assault on state institutions and free trade has raised the question of which Australian leader may be better placed to “manage” President Trump.

It has also coloured perceptions of any campaign moves that appear a little too close to the MAGA playbook, including proposals to dispense with diversity and inclusion programs in government and schools, as well as shrinking the public service.

Talk of whether China is the “number one threat” to Australia’s security and influence speaks to anxieties about the superpower’s growing presence across the region.

Electoral observers pore over signals over which party might achieve a better working relationship with their Chinese counterparts.

Politics & Society

Disinformation damages democracy, but perhaps not in the way you think

The furore concerning the prospect of a Russian military base in Indonesia was a rare example of politics in Asian countries (beyond China) intruding into Australia’s federal election campaign.

It reminds us that it is equally crucial for the next government to get a real handle on the fast-moving developments affecting Asia more widely.

My new report aims to detail the challenges facing democracy across Asia by analysing eight countries across the region. Alongside India and Indonesia – two of the world’s largest democracies – I examine Mongolia, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand.

My findings paint a concerning picture of deepening democratic regression and crisis.

Governments are using a wide range of measures to undermine independent state institutions, restrict the opposition, manipulate elections and muzzle civil society.

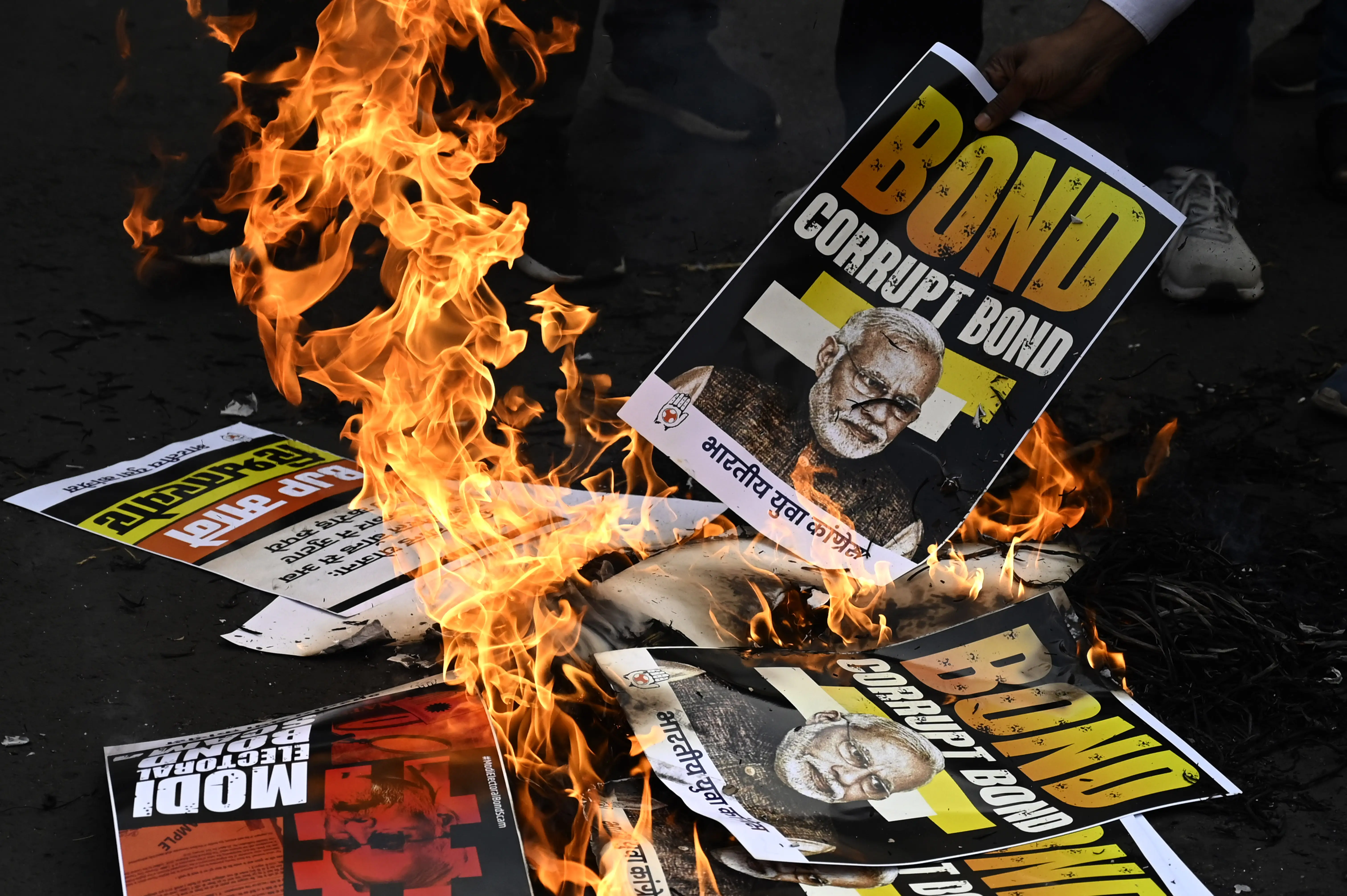

Particularly stark is the ongoing democratic decline and rise of “predatory populism” in Australia’s largest near neighbour, Indonesia, and “despotism” in security ally India – a key member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), alongside Japan and the USA.

By contrast, former President Yoon’s attempt at a "self-coup" in South Korea last December has shown how politicians, institutions and citizens can work together to push back against would-be autocrats.

It culminated in his recent impeachment.

Of course, Australia’s foreign policy has long differed from US policy in its lesser focus on promoting democracy.

This muddling through was understandable in past decades when, despite a wide diversity of political systems, the prevailing assumption was that states across the region (even China) were liberalising toward a more recognisably democratic future.

However, current developments require serious reflection on how Australia will navigate a new reality in which key states across Asia are becoming more autocratic, and what this means for our foreign policy.

For too long, this much-needed conversation has been overshadowed by the dominant focus on defence and Australia’s ‘hard’ power, exemplified by the Quad, the AUKUS alliance and the push for nuclear submarines.

Indeed, analysis of the main campaign pledges made in this election can reduce foreign policy issues to defence spending, as though there is little else to be discussed.

A re-oriented and expanded foreign policy might focus on three pillars.

Firstly, a focus on ‘navigating autocracy’ would strengthen funding and capacity across government, civil society and the university sector in Australia to better understand the major political transformations in states across Asia.

In particular, it would support a more clear-eyed view of Australia’s indispensable and strengthening, yet fraught, ties with India.

That, of course, would run counter to policies spanning successive governments that have hamstrung our knowledge ecosystem, including universities’ current funding crisis. The need for Australia to step up has intensified with the Trump administration’s gutting of US funding for research.

Secondly, a focus on ‘democratic solidarity’ would entail fuller thinking on how Australia might bolster and expand its ties with enduring democracies in the region, like Japan, as well as those weathering serious challenges while showing resilience, like South Korea.

Taiwan’s offer to help counter online disinformation in the run-up to Australia’s elections is one example of what fuller democracy-to-democracy cooperation might look like.

Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

A third pillar, bridging foreign and domestic policy, would focus on ‘bringing lessons home’.

Australian policymakers have much to learn from current experiences of both democratic regression and democratic resilience across Asia to ensure the continued vitality and viability of Australian democracy at all levels.

The second and third pillars, in particular, would be more productive than a distortive fortress mentality that views foreign relations solely in terms of threat levels.

In Europe, for instance, the EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell was roundly criticised in 2022 for characterising Europe as a “garden” and the rest of the world as mostly a “jungle”.

These pillars would also avoid the trap of thinking in neo-colonial terms of an Australian ‘sphere of influence’ – reflected in recent discussions of Australia being “outplayed” by Russia and China in its “own backyard”.

Instead, they spur us to think of foreign relations in terms of democratic solidarity, multilateralism and mutual benefit.

In this election, as many observers have noted, Australia finds itself at a crossroads.

As the country navigates the new and confronting reality of a 'post-America Asia', it needs to build its capacity to better understand its neighbours, foster new alliances and make more of its existing relationships.