Environment

Who’s running late for the Paris Agreement?

After two weeks of negotiations at COP24, almost 200 countries have now agreed on a ‘rule book’ to enforce the Paris Agreement on climate change

Published 18 December 2018

The 24th annual UN climate conference has just concluded under grey skies in Katowice, Poland.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 24) saw parties broadly agree on key elements of a ‘rule book’ to assist the implementation of the historic Paris climate agreement that came into force in 2016.

Although there is still work to be done, progress was made with respect to emissions counting and reporting, and on important aspects relating to finance.

The debates at the conference also highlighted some of the greatest challenges and opportunities that underscore the need for urgent action across the globe.

The urgency of addressing these challenges was perhaps best summed up by United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, who said that “to waste this opportunity in Katowice would compromise our last best chance to stop runaway climate change. It would not only be immoral, it would be suicidal”.

Environment

Who’s running late for the Paris Agreement?

One of the Paris Agreement’s central goals is for Parties, through collective action, to “hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”.

In October the world’s leading climate scientists produced, through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a special report centred around a scenario of 1.5°C in global warming.

They cautioned that a global average temperate increase above 1.5°C would significantly worsen the risk of extreme heat, drought floods, and poverty for hundreds of millions of people, and would lead to environmental impacts like the loss of hard coral reefs.

The report found that global carbon dioxide equivalent emissions need to decline by 45 per cent by 2030 and should reach zero net emissions around 2050.

Reaching ‘net zero’ will depend on carbon ‘sinks’ which retain carbon in soils, forests and woodlands, as well as in the ocean and coastal systems (‘blue carbon’) including seagrasses and mangroves.

Guterres’ warning was reflecting the urgency pronounced by the IPCC, but also served as a call to action: countries are invited to revise and resubmit their national commitments for the 2020-2030 period by the next climate conference in 2020.

Presently, the sum total of national commitments has been found to be well short of what would be required to limit temperature increases to 2°C - much less 1.5°C.

While major economies including India and China may already be on track to exceed their commitments, others are falling short, including the USA.

Environment

Trump’s political climate

Many countries – including Australia, Canada and the EU – can do much more.

The Secretary General will convene a high-level political climate summit in September 2019 to assist in the review of countries’ commitments.

Katowice saw greatly enhanced public and private sector finance commitments for low-carbon technologies including renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies, as well as for climate adaptation.

A group of 415 private investors with USD $32 trillion assets-under-management called for more private sector investment to support ‘cleaner’ economies, and equitable transitions away from fossil-fuel dependency.

But much more is needed both from governments and the private sector. Innovation with the public sector leveraging private investment, like the successes of the Australian Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the UK Green Bank, could be used at a much larger scale.

The conference also highlighted success stories.

The rapid global uptake of renewable energy and energy efficiency, advances in energy storage, public transport improvements and changes in the design of cities and electric vehicles, and forest conservation successes in the face of huge challenges, for example, demonstrated technology and policy breakthroughs.

Universities and other knowledge institutions together with governments and the private sector can contribute to speeding and scaling up the adoption of climate policies and technologies that could lead to further positive change.

Sciences & Technology

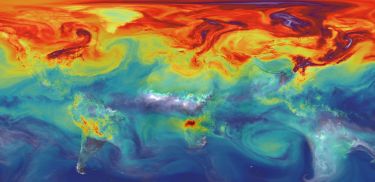

Key greenhouse gases higher than any time over last 800,000 years

But some of the deep and challenging political tensions holding back progress were also exposed.

A report like the IPCC’s 1.5°C report would usually be ‘welcomed’ in official COP decisions. But the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait caught delegates by surprise by opposing a welcome, proposing only to ‘note’ the report.

This reticence likely indicates that climate leadership will not come from the United States in the coming crucial two-year period leading up to the COP in 2020.

Perhaps the time has come for the Asia-Pacific region including Australia - the region of the world most highly threatened by the impacts of climate change and the most likely to benefit from the rapid growth of clean economies – to step into this leadership opportunity.

We need climate action now, for our own prosperity and wellbeing, and that of all life on Earth.

Banner: Getty Images