Health & Medicine

Predicting premmies: The test that could save babies’ lives

How a simple technique greatly increases the chances of collecting infant urine samples when you need them

Published 9 April 2017

Managing when a baby wees may seem like black magic to parents who are all too familiar with the unpredictable nature of an infant’s toilet habits.

“They call infant urine samples ‘liquid gold’ for good reason,” says Dr Jonathan Kaufman, a doctor at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne.

“Baby wee can be elusive.”

This trickiness can make collecting a urine sample from an infant difficult. But Dr Kaufman, who is also a researcher at the University of Melbourne and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, has developed a simple method that encourages babies to urinate, greatly increasing the chances of collection.

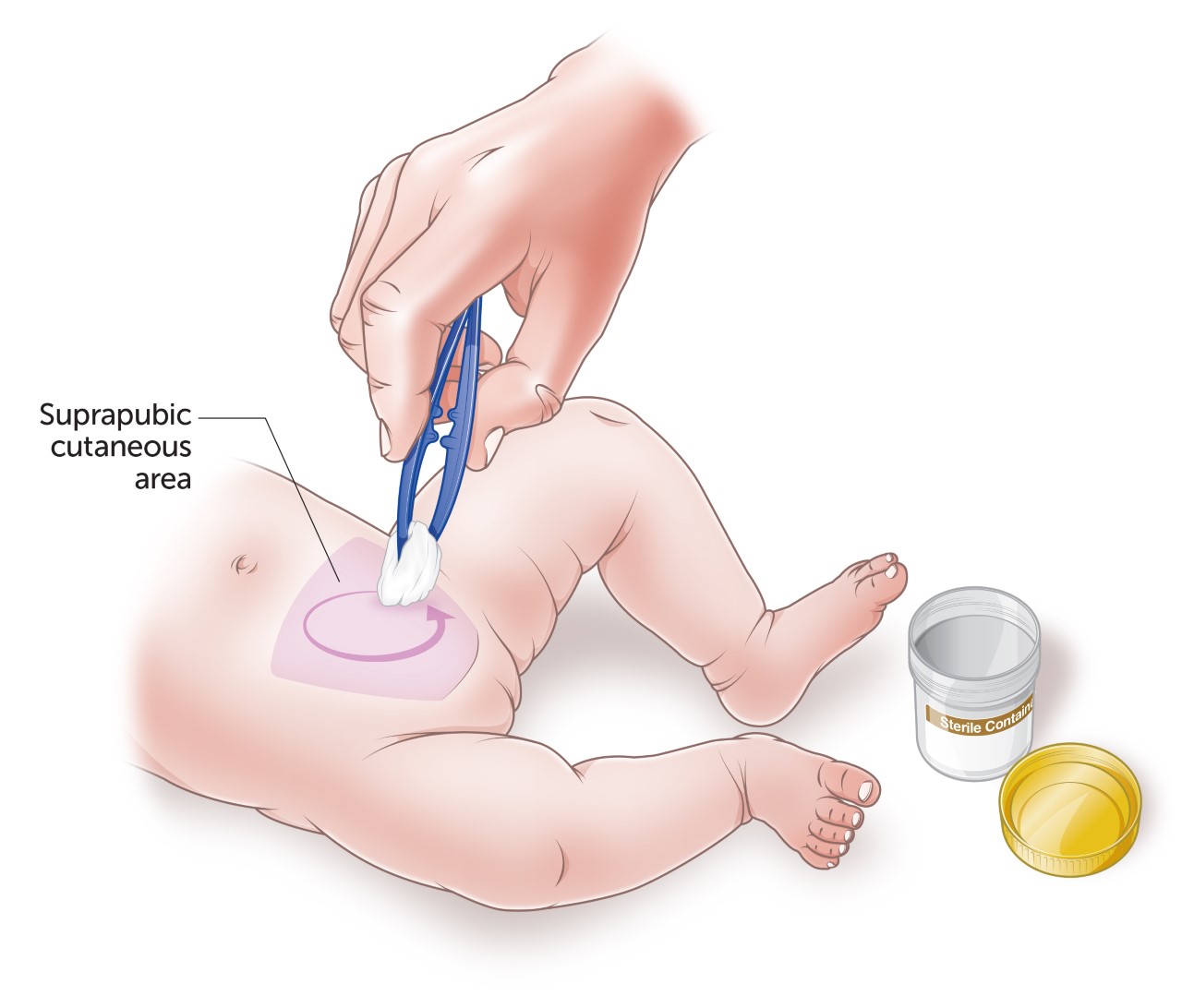

Known as Quick-Wee, and recently published in The BMJ, the method involves gently rubbing the lower abdomen in circular motions with a piece of gauze soaked in cold liquid, to trigger urination.

Current methods for collecting a urine sample from an infant can be, at best, time consuming and, at worst, distressing.

When doctors suspect a baby may have a urinary tract infection (UTI) they often use a method known as Clean Catch, where they wait for the infant to go to the toilet spontaneously, and use a cup to ‘catch’ the urine. This can take a long time and has a high failure rate, as well as a risk of sample contamination.

If Clean Catch fails or time is of the essence, clinicians may need to use a catheter or a needle (extracting the urine directly from the bladder) to collect the sample, which is invasive and painful.

“The signs of UTI in young children are very non-specific, and collecting a sample for diagnosis is difficult,” explains Dr Kaufman.

“So in practice some children don’t have a urine sample collected at all, and are prescribed antibiotics when a UTI is suspected but not confirmed, meaning they receive antibiotics they don’t need.

“Other times there is a delay starting treatment when they do have a UTI.”

Health & Medicine

Predicting premmies: The test that could save babies’ lives

Dr Kaufman first conceived Quick-Wee when he was working night shifts as a paediatric trainee. He noticed that cleaning the skin in preparation for inserting a catheter often triggered babies to urinate.

“I wondered if this could form the basis for a more formal method of collecting urine samples,” he says.

“Then one night there was a baby in the emergency department who really needed a urine sample, but the junior doctor wasn’t able to do a catheter.

“I couldn’t get down there straight away, so I asked the doctor to get everything ready for a catheter, and to keep cleaning the skin while they waited with a cup ready in case they could catch some wee.

“It worked, they had collected a urine sample by the time I got there.”

Dr Kaufman and his team trialled the method with 354 babies under 12 months who needed a urine sample in the Royal Children’s Hospital emergency department.

For half the children the doctor or nurse tried to collect a urine sample using Quick-Wee, while the other half used the standard Clean Catch method, for up to five minutes.

Thirty-one percent of patients urinated within five minutes with the Quick-Wee method, compared to only 12 per cent with standard Clean Catch.

“Our trial showed that Quick-Wee can speed up urine collection for many babies,” says Dr Kaufman.

“Collecting the sample quickly means the clinician can test for a UTI in a timely fashion, and either treat with appropriate antibiotics, or move on and look for other diagnoses,” he says. “It also decreases the chances of needing an invasive collection method, like a catheter or a needle, for some children.”

But perhaps the most satisfying result for Dr Kaufman was when he used Quick-Wee for his own infant daughter.

“We were away visiting family in the country, and she had a fever and was vomiting all night,” he recalls.

“The doctor in the emergency department there wanted to check a urine sample, so we used Quick-Wee. We collected a sample within a few minutes, which meant she didn’t need a needle or catheter procedure, and there was no delay in starting her antibiotic treatment.”

Quick-Wee works by triggering early childhood cutaneous voiding reflexes - nerves on the skin which, when stimulated in young children, trigger involuntary urination. There is a similar process in some animals, whose mothers lick the perineum to stimulate the perigenital-bladder spinal reflexes in their young.

Because most children develop voluntary control of their bladder function by three years of age, Quick-Wee is best suited to younger children and is likely to be most effective for infants under one.

For Dr Kaufman, Quick-Wee’s simplicity is key to its success.

“It’s a very pragmatic and easy method that can be used anywhere: in big hospitals, in the community, in general practice, and in resource-limited settings like remote areas or where equipment or paediatric medical services are not easily accessible,” he says.

And, as an added bonus, he now has a good line of wee jokes for medical conferences.

“I do like to share my wee-search,” he laughs.

Banner image: PressReleaseFinder / Flickr