Health & Medicine

A chip off the DNA block

Two new mammogram imaging techniques could revolutionise breast screening by predicting each woman’s cancer risk

Published 23 December 2020

First established in 1991, Australia’s national breast screening program, BreastScreen, has saved many lives through early detection of breast cancers.

The joint Australian and state/territory government program funds free mammograms every two years for all women aged between 50 and 74 years. Women can also receive a free mammogram in their 40s.

A recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report found that 55 per cent of women in the 50–74 target group were screened in 2017–2018.

Health & Medicine

A chip off the DNA block

This is commendable but especially as our population ages we need to increase the numbers of women presenting for screening and the accuracy of screening (detecting cancers) while decreasing unnecessary call-backs.

Published in the International Journal of Cancer, our latest research has found two new ways to predict breast cancer risk from mammograms.

When these measures are combined, they are much more effective in stratifying women in terms of their risk of breast cancer than all the known genetic risk factors. The new method could therefore greatly improve breast screening by allowing it to be tailored to each woman’s risk at minimal extra cost.

In terms of understanding how much women differ in their breast cancer risk, these developments could be the most significant since the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 were discovered 25 years ago.

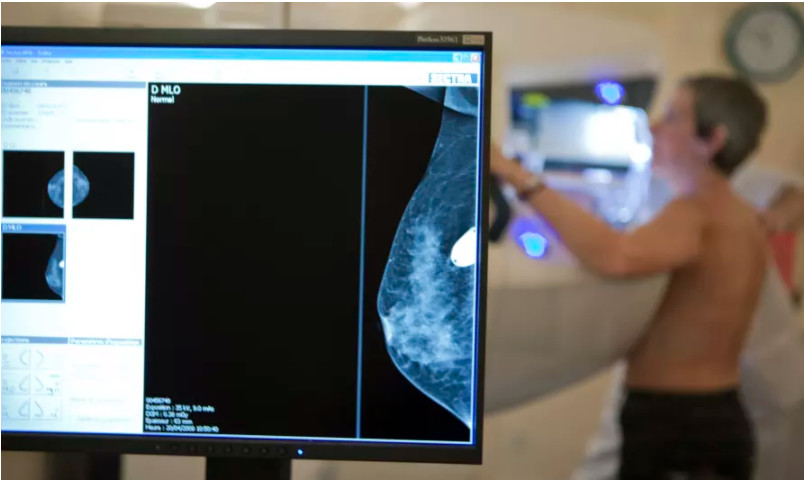

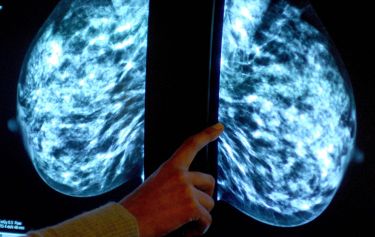

Breast screening involves low dose X-ray images of each breast with the primary aim of detecting breast cancers early when they are smaller, easier to treat, and more likely to be cured.

Breast cancer mortality has decreased since the service began, from 74 deaths per 100,000 women aged 50 to 74 in 1991, to 40 in 2018, although many other factors have also played in a role in this almost halving of deaths from breast cancer.

Health & Medicine

Filling in the genetic blanks of breast cancer predisposition

The need to change the program has been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic which interrupted service delivery in 2020. This created a backlog for an already stretched service and poses an additional challenge for population screening.

By having breast screening tailored to each woman’s risk, resources could be better allocated and more accurate. Busy radiologists could be alerted to women at higher risk of breast cancer, and of having breast cancers missed at screening. Future screening could be made more appropriate and personalised.

Since the late 1970s, scientists have known that women with denser breasts, which show up on a mammogram as having more white or bright regions, are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer.

Women with greater breast density are also more likely to have existing breast cancers missed at screening. This problem of ‘dense breasts’ is attracting growing concern from community groups and breast screening services across the world.

Over the last five years we have developed two new measures of breast cancer risk that arise from examining mammograms in different ways.

Health & Medicine

New immune cells help maintain breast health

Collaborating with Cancer Council Victoria, BreastScreen Victoria and other researchers across the world, we have been the first to use mammograms to find other ways of investigating breast cancer risk.

Our latest study involved participants in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study run by the Cancer Council Victoria, and the Australian Breast Cancer Family Study and Twins Research Australia run from the University of Melbourne.

Participating women filled out a questionnaire and allowed researchers to access their mammograms from BreastScreen, other providers or their own copies.

We used computer programs to analyse mammogram images of large numbers of women with and without breast cancer. We found and confirmed two new measures for extracting risk information to develop two new mammogram-based risk measures called Cirrocumulus (based on the image’s brightest areas) and Cirrus (based on the image’s texture).

We first used a semi-automated computer method to measure density at the usual, and successively higher levels of brightness to create Cirrocumulus. We then used artificial intelligence and high-speed computing to learn about new aspects of a mammogram that predict breast cancer risk and created Cirrus.

When the Cirrocumulus and Cirrus measures were combined, they substantially improved risk prediction beyond that of all other known risk factors. This applied both to predicting breast cancer diagnosed at future regular screens (screen-detected cancers) as well as to predicting breast cancer diagnosed between regular screens (interval cancers).

Health & Medicine

5 discoveries we can thank twins for

Given mammography is now digital, and our measures are now computerised, this research could lead to women being assessed for their breast cancer risk at the time of screening – automatically. They could then be given recommendations for their future screening based on their risk, not just their age.

This tailored screening – not ‘one size fits all’ – could be more accurate and better identify women at high, as well as low, risk so that their future screening can be adjusted accordingly.

If successfully adopted, these measures could make screening more effective in reducing breast cancer mortality and help address the problem of dense breasts. The extra cost would be minimal as they simply use computer programs. Family history data collected by BreastScreen could also easily be used to even better predict risk for some women.

Adoption of these new measures could also be used to ease pressure on BreastScreen in handling the COVID backlog with limited resources.

If it becomes well-recognised that screening can be used to more accurately assess risk, more women might be encouraged to be screened and the participation rate increased.

Women found to be at high risk based on their mammogram would also benefit greatly from knowing their genetic risk, especially if they have a family history.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer affecting Australian women, with an estimated 20,000 diagnosed in 2020. If we can further improve early detection, and do so on more effective way, more of them may beat this insidious disease which is increasing across the world.

Dr Kevin Nguyen at the University of Melbourne, starting with his ground-breaking PhD, created the Cirrocumulus measure in an on-going collaboration with researchers from Seoul National University in South Korea, The application of artificial intelligence was led by Dr Daniel Schmidt, now at Monash University, and Dr Enes Makalic when working at the University of Melbourne.

Banner: Getty Images