Sciences & Technology

What the past can tell us about the future of climate change

The new global norm of extreme weather-related disasters and climate change requires a new type of disaster-resilience modelling

Published 31 October 2018

Extreme events are on the rise globally.

Indonesia was recently hit by a devastating earthquake and tsunami. Hurricane Florence and Typhoon Mangkhut wreaked havoc in America and East Asia on the same day in September this year and recently the Indian state of Kerala suffered the worst flood in a century.

Australia has also endured its worst-ever cluster of bushfires and floods, with Black Saturday in 2009 and the Brisbane Floods in 2011 causing unprecedented destruction. The current drought in New South Wales and Queensland is on track to be one of the harshest this century.

If recent trends and the latest climate change impacts assessment become the new norm - the worst is yet to come.

At the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructure and Land Administration (CSDILA) and Centre for Disaster Management and Public Safety (CDMPS), we have developed the Intelligent Disaster Decision Support System (iDDSS) to simulate disaster scenarios and their potential impacts.

Sciences & Technology

What the past can tell us about the future of climate change

This new system means disaster-resilience modelling can be embedded in community engagement from the outset, to support urban planning and infrastructure development.

Australia has a well-earned reputation for being a land of extremes – from cyclones to bushfires and floods to drought. This high variability can make it difficult to prepare for all eventualities. But scientists are gaining a better understanding of the likelihood and consequences of extreme events.

In 2016, the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO published a report warning that hotter, drier and longer summers significantly raised the possibility of drought. Now, New South Wales and Queensland are facing one of the worst droughts in living memory.

Australia’s previous experience with severe droughts, like the Millennium Drought between 2001 and 2009, which led to mature strategies for drought response including restriction policies, contingency supplies, irrigation efficiency improvements, crop mix alterations and water trading.

But as that drought lengthened, the conditions were well beyond the scope of these mitigation strategies. Persistent declines in rainfall and runoff contributed to widespread water supply shortages, crop failures, livestock losses, dust storms and bushfires.

Although valuable lessons came out of that experience, it may be that future droughts will be more severe in unexpected ways. We need to explore new scenarios and assess their impacts, depending on our preparedness and capability.

This is where research can add value.

Politics & Society

What do Gen X and Gen Y worry about most? Climate change.

When we are not adequately prepared, we take one step forward by investing in new infrastructure or development projects for our cities and towns and two steps back when disaster strikes.

Our Intelligent Disaster Decision Support System helps determine what areas of a building or region may be at higher risk; what preventative measures could strengthen infrastructure; and ensures accurate numbers, timing and measures for emergency services to evacuate people from any given area.

For example, a flood damage impact analysis in Maribyrnong, a suburb 8 km north-west of Melbourne shows the damage curves, with corresponding damage level to buildings based on the depth of water.

This kind of modelling could help policymakers and infrastructure decision-makers focus on improving systems that could most significantly reduce socio-economic impacts.

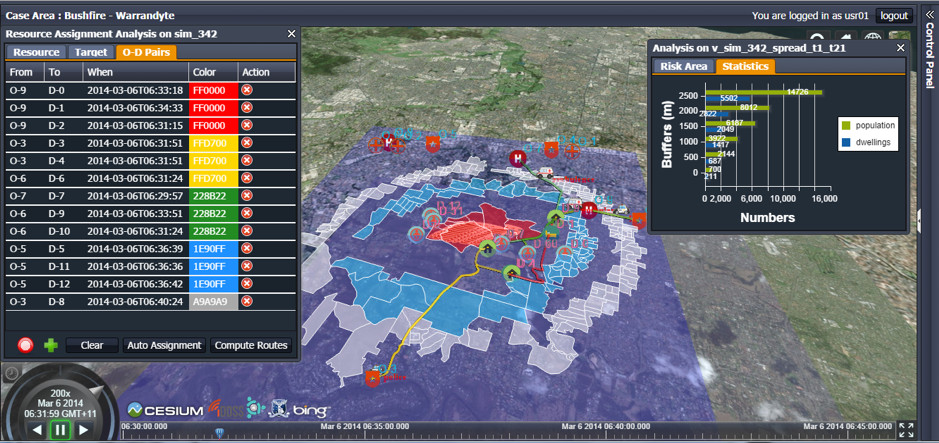

Similarly, a simulation of the risk facing different areas based on their distance from a fire front in Warrandyte (a north-east suburb in Melbourne, 24km from CBD) helps analyse who is impacted; which households, vulnerable locations (such as aged care, schools, hospitals), and road networks.

This information could be used by emergency management personnel to plan rescue and evacuation operations, before the fire front reaches the area.

Ineffective or inadequate disaster resilience planning impedes sustainable development efforts.

United Nations (UN) agencies have explicitly linked the Sustainable Development Goals (a group of 17 global goals set by the General Assembly in 2015) with better management of disaster risk, as outlined in its Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

We have mapped how priority research areas in disaster management can contribute to each of the Sustainable Development Goals; partnerships and collaborations are essential – across disciplines and sectors, locally and internationally – to prepare for disaster in towns and cities of the future.

Environment

Mental health in a changing climate

In Australia, state authorities and agencies recommended measures for specific disasters, like bushfires. Following Black Saturday, for example, the Country Fire Authority (CFA) launched the Community Led Planning Project which assisted 17 of Victoria’s most high-risk communities to develop their own risk-reduction plans.

The result was stronger, more connected and prepared communities.

Following this success, the CFA partnered with Emergency Management Victoria and other emergency and local government agencies to implement similar projects across Victoria. A review of the Wye River – Separation Creek bushfire on Christmas Day 2015, showed community-focused programs for emergency preparedness positively influenced community response.

Only a month before the fire, the Wye River CFA convened a community meeting to discuss fire response. Community members credited this with helping them change to an ‘evacuate’ mindset in the event of a major fire - originally they would often stay.

The Christmas day bushfires destroyed 116 houses in Wye River and Separation Creek, but early evacuation meant no deaths.

Families and communities coming together to talk about what to do when disaster strikes has real power to save lives.

Outcomes will be even better if we apply our improving knowledge of evolving disaster risks, and new tools like our novel system - to anticipate how certain infrastructures and communities will hold up in a disaster, and how we might better contain and mitigate the impacts.

We hope to support policy-makers, individuals and communities alike to become more disaster resilient, and to continue to contribute to a more sustainable future.

Banner image: Alexander Gerst/ NASA