Environment

How did it come to this?

A new report for the government that investigates the causes of the recent mass fish deaths in the lower Darling River finds climate change and water access agreements helped create a deadly mix

Published 10 April 2019

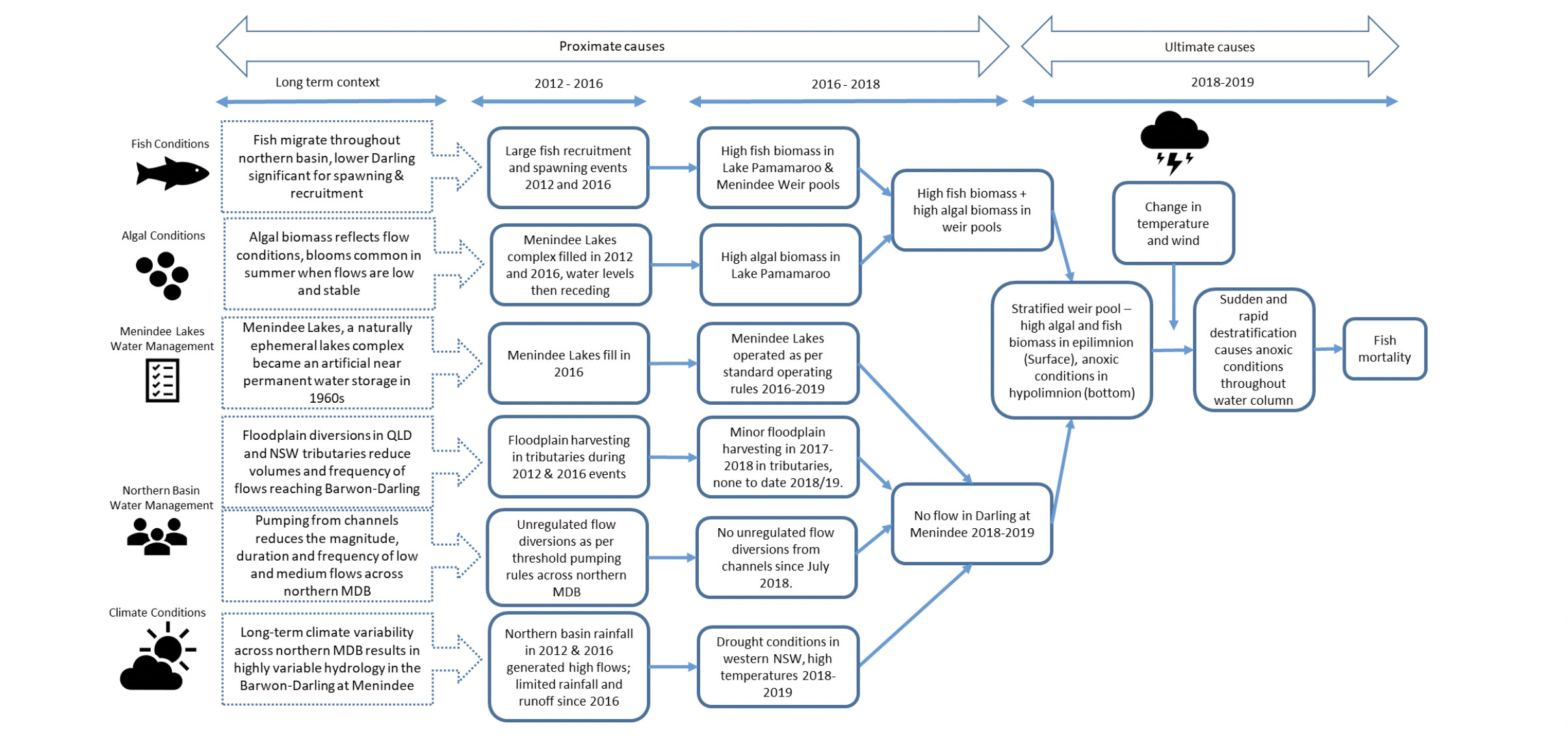

Over summer, three significant fish death events occurred in the lower Darling river, near Menindee, New South Wales. These events involved the native species Murray Cod, Silver Perch, Golden Perch and Bony Herring, with mortality numbers estimated to be in the range of hundreds of thousands to more than a million fish.

They were a serious ecological shock to the lower Darling region.

Our report for the Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources, David Littleproud, examines the causes of these events and recommends actions to mitigate the potential for repeat events in the future.

Our final report summarises what we found and what we recommend.

High-flow events in the Darling River in 2012 and 2016 filled the Menindee Lakes and offered opportunities for substantial fish breeding, which was further aided by the targeted use of environmental water.

Environment

How did it come to this?

The result was very large numbers of fish in the lakes and weir pools around Menindee. After the lake-filling rains of late 2016, two very dry years ensued, resulting in very low inflows into the Barwon-Darling river.

As the supply of water dried up, the river became a series of disconnected and shrinking pools. As the extremely hot and dry conditions in late 2018 took hold, the large population of fish around Menindee became isolated within weir pools.

Hot weather, low rainfall and low flows provided ideal conditions for algal blooms and thermal stratification in the weir pools, resulting in low oxygen concentrations within the bottom waters.

With the large fish population now isolated in the oxygenated surface waters of the pools, all that was needed for the fatal blow was a trigger for the water profile to mix.

This trigger arrived on three separate occasions, with changes in the weather that brought sudden drops in temperature and increased wind that caused sudden turnover of the low oxygen bottom waters.

With the fish already stressed by high temperatures, they were now unable to gain sufficient oxygen from the water to breathe and a very large number of them died. As we write, the situation in the lower Darling remains dire, and there is a risk of further fish deaths if there are no significant inflows to the river.

Fish deaths caused by these sorts of turnover events are not uncommon, but the conditions outlined make these events unusually dramatic.

So, how did such adverse conditions arise in the lower Darling river and how might we avoid a reoccurrence?

We’ve examined four influencing factors; climate, water management, lake operations and fish mobility.

Sciences & Technology

Repairing the Murray-Darling Basin

We found that the fish death events in the lower Darling were preceded and affected by exceptional climatic conditions.

Inflows to the water storages in the northern Basin over 2017-18 were the second lowest for any two-year period on record. Most of the Murray-Darling Basin experienced its hottest summer on record, exemplified by the town of Bourke breaking a new heatwave record for NSW, with 21 consecutive days with a maximum temperature above 40°C.

We concluded that climate change amplified these conditions and will likely result in more severe droughts in the future.

Changes in the water access arrangements in the Barwon–Darling River, made just prior to the commencement of the Basin Plan in 2012, exacerbated the effects of the drought.

These changes enhanced the ability of irrigators to access water during low-flow periods, meaning fewer flow pulses make it down the river to periodically reconnect and replenish isolated waterholes that provide permanent refuge habitats for fish during drought.

We conclude that the Lake Menindee scheme had been operated according to established protocols, and was appropriately conservative given the emerging drought conditions. Low connectivity in the lower Darling resulted in poor water quality and restricted mobility for fish.

Environment

How to prevent cities from drying up

Given the right mix of policy and management actions, Basin governments can significantly reduce the risks of further fish death and promote the recovery of affected fish populations.

The Basin Plan is delivering positive environmental outcomes and more benefits will accrue once the plan is fully implemented.

But more needs to be done to enhance river connectivity and protect low flows, first flushes and environmental flow releases in the Barwon-Darling river.

Drought resilience in the lower Darling can be enhanced by reconfiguring the Lake Menindee Water Savings Project, modifying the current Menindee Lakes operating rules and purchasing high-security water entitlements from horticultural enterprises in the region.

In Australia, water entitlements are the rights to a share of the available water resource in any season. Irrigators get less (or no) water in dry (or extremely dry) years.

A high-security water entitlement is one with a high chance of receiving the full water allocation. In some systems, although not all, this is expected to happen 95 per cent of the time. And these high-security entitlements are the most valuable and sought after.

Fish mobility can be enhanced by removing barriers to movement and adding fish passageways. It would be beneficial for environmental water holders to place more of their focus on sustaining fish populations through drought sequences.

The river models that governments use to plan water sharing need to be updated more regularly to accurately represent the state of Basin development, configured to run on a whole-of-basin basis, and improved to more faithfully represent low flow conditions.

There are large gaps in water quality monitoring, metering of water extractions and basic hydro-ecologic knowledge that should be filled.

Sciences & Technology

The limits of modelling: Knowing we don’t know

Risk assessments need to be undertaken to identify likely fish death event hot spots and inform future emergency response plans.

All of these initiatives need to be complemented by more sophisticated and reliable assessments of the impacts of climate change on water security across the Basin.

Responding to the lower Darling fish deaths in a prompt and substantial manner provides governments an opportunity to redress some of the broader concerns around the management of the Basin.

To do so, Basin governments must increase their political, bureaucratic and budgetary support for high value reforms and programs, particularly in the northern Basin.

All of our recommendations can be implemented within the current macro-settings of the Basin Plan and do not require a revisiting of the challenging socio-political process required to define Sustainable Diversion Limits – which is how much water can be used in the Murray–Darling Basin.

Successful implementation will require a commitment to authentic collaboration between governments and local communities, and sustained input from the science community.

A version of this article was co-published with The Conversation.

Banner: AAP Photos