Health & Medicine

The vaccine that may help prevent type 1 diabetes

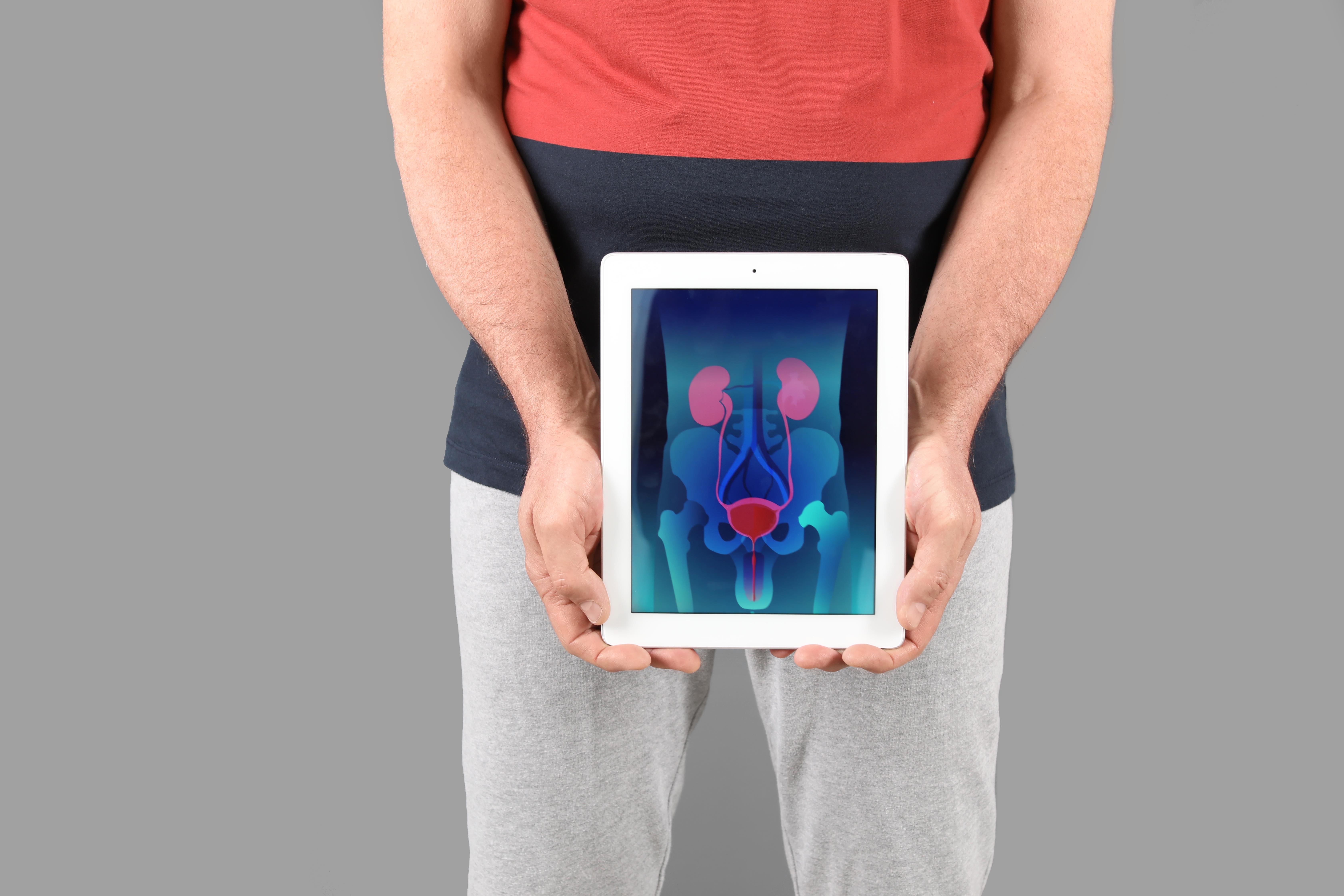

By blocking a cancer cell’s access to the ‘fuel’ it needs to grow, researchers hope to develop a new therapy for prostate cancer

Published 7 February 2019

An old military tactic, widely used in Roman and medieval times, is now being put to good use in cancer research.

The idea is that if you starve out your enemy - they will either submit or die. And in the race to develop treatments for prostate cancer, starving out those hostile cancer cells is proving effective.

Metabolic biologist at the University of Melbourne, Professor Matthew Watt, teamed up with Associate Professor Renea Taylor, a cancer biologist from Monash University Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) to better understand how cancer grows, what it feeds on and how to deny it these resources in order to improve tumour treatment.

“We chose to focus on prostate cancer many years ago,” says Professor Watt, head of the Department of Physiology at the University of Melbourne.

Health & Medicine

The vaccine that may help prevent type 1 diabetes

“Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in men, and the second leading cause of cancer death. But we now see younger men getting prostate cancer earlier than ever before and we wanted to explore why that was,” says Professor Watt.

Statistical analysis by other groups shows that obesity is associated with getting more severe prostate cancer. In particular, men who consume more saturated fatty acids had more aggressive progression of the disease and poorer outcomes.

Fatty acids are the building blocks of the fat in our bodies and in much of the food we eat, and they are increased in the blood of obese men compared with lean men.

“So, a key question for us was whether fats produced in the body played a particular role in prostate cancer development,” says Professor Watt.

Samples of prostate cancer and normal tissue were taken from patients.

The two types of tissue, cancerous (malignant) and normal (benign) tissue were examined for the type of ‘fuel’ they used.

“In the first experiments, we showed that fatty acids were taken up into prostate cancer cells and increased tumour growth,” says Associate Professor Taylor.

“In contrast, we saw that normal tissue had a preference for using the sugar glucose as fuel for growth.”

Health & Medicine

Pioneering nurse-led cancer care

Fatty acids move into the body’s cells via a transporter, a type of dedicated channel in the cell wall. And this particular transporter, CD36, is associated with highly aggressive cancers.

“Our next step was to genetically delete the transporter to see what happened without it,” Associate Professor Taylor says.

“We found that the deletion slowed the cancer’s development by 30 to 50 per cent compared with the samples without this deletion.”

The team now understood more about the transporter’s integral function in prostate cancer’s growth, and turned their attention to investigating how a potential therapy could work by stopping it functioning.

“We designed antibodies that specifically targeted the CD36 transporter. By binding to the transporter, the antibodies effectively create a roadblock for fatty acids trying to enter the cell,” says Professor Watt.

“The antibodies were then applied to organoids, an artificially grown mass of cultured prostate cells that resembles the organ.”

And results are very promising says Professor Watt.

“The treated organoids showed a 90 per cent reduction in growth. This was a really pleasing outcome, but perhaps more hopeful was that this treatment also stopped the signalling or communication between lipids and the cancer.”

“Stopping this signalling was part of the reduction in tumour growth.”

With sights set on a potential treatment, the idea is that the antibodies would block some, but not all, fatty acid transporters as we need some of these fatty acids to maintain normal functions in non-cancerous cells.

Health & Medicine

Defining a pathogen

“Applying knowledge of the metabolism to cancer and providing the evidence to develop a therapy to treat a disease that impacts so many men is deeply satisfying,” Professor Watt says.

“Our whole concept is about giving more appropriate treatment earlier to stop men getting to the late or advanced stage of prostate cancer.”

The ultimate goal is combining the fatty acid therapy and existing treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy at lower doses to kill the cancer and reduce any side effects.

The research was funded by Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, the Diabetes Australia Research Trust and the Cancer Council Victoria.

Banner: Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) image showing adipocytes (white oval shapes; which store vast amounts of fatty acids) in close contact with prostate cancer. Arrow indicates direct cell–cell contact between cancer cells and adipocytes/Renea Taylor and Matthew Watt.