Protecting Australia’s citrus industry

Researchers have identified an Australian strain of fungus that causes citrus rot, calling for effective controls to protect the citrus industry

Published 10 May 2021

In Australia we are lucky enough to be able to squeeze fresh orange juice for breakfast, or peel a mandarin for a quick snack at work or school.

Bright and juicy citrus fruits taste great and their vivid colour is a reminder of the health-giving vitamins within. So, a dark mark on the skin can detract from these positive associations, and many consumers will be put off buying them.

A dark, tear-shaped mark is often a sign of the fungal disease anthracnose, which is a a major issue for international citrus producers, having been reported from citrus production areas in 22 countries.

The disease affects citrus in the pre-harvest stage by reducing tree health and yield in the orchards while post-harvest anthracnose affects fruit quality, reducing the marketability of the fruit as a result of dark markings.

Australia is a major citrus producer with lemons, oranges and mandarins grown in every mainland state. There is approximately 26,000 hectares of citrus production in Australia.

In 2017–18 Australia’s orange, mandarin, lemon, lime and grapefruit production was valued at $A786 million, generating $A428 million worth of exports. Major export markets include China, Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, Singapore, the USA and Thailand.

Any post-harvest anthracnose infection may also be a biosecurity risk for the importing country, which would damage Australia’s reputation in the international citrus industry.

The fungal plant pathogen that causes anthracnose is the Colletotrichum species. There are over 250 Colletotrichum species globally that infect a very diverse range of plants, of which 27 species are associated with citrus anthracnose.

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides is the most important pathogen causing citrus anthracnose and has been found in over 15 countries. Globally, over 26 other species are associated with the disease.

Sciences & Technology

An ounce of biosecurity prevention is worth two pounds of cure

Our research group at the University of Melbourne analysed Colletotrichum collected from samples of anthracnose lesions on citrus leaves, twigs and fruit from Victoria and New South Wales, as well as from State fungaria (the Victorian Plant Pathology Herbarium (VPRI), the Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium (BRIP) and the NSW Plant Pathology Collection (DAR).

The study identified six Colletotrichum species infecting Australian citrus. One of these is a new species – Colletotrichum australianum – named after the country where the pathogen was first identified.

The results revise current thought about the diversity of Colletotrichum species that cause anthracnose of citrus in Australia. Among the four species that have been previously reported as pathogens associated with citrus anthracnose in Australia, only C. fructicola and C. gloeosporioides were found in this study.

The other three Colletotrichum species, C. theobromicola, C. karstii and C. siamense, have been recorded as pathogens of a broad range of plants in Australia (including coffee, jackfruit and fig) but never previously associated with citrus anthracnose. It is also the first time that C. theobromicola has been reported anywhere in the world as a pathogen of citrus.

Protecting our industry

The identification of new Colletotrichum species pathogenic to citrus in Australia requires further research to develop and implement appropriate control methods. So how can we protect Australia’s citrus industry better?

Environment

Biosecurity and the beekeeper

First we need to understand the plant disease.

We were able to confirm not only the presence of the pathogen, but to understand which species were actually associated with causing disease.

The relationships between the Colletotrichum species were determined by analysing the DNA sequences of the fungal pathogens, to produce tree-like diagrams called phylogenetic trees.

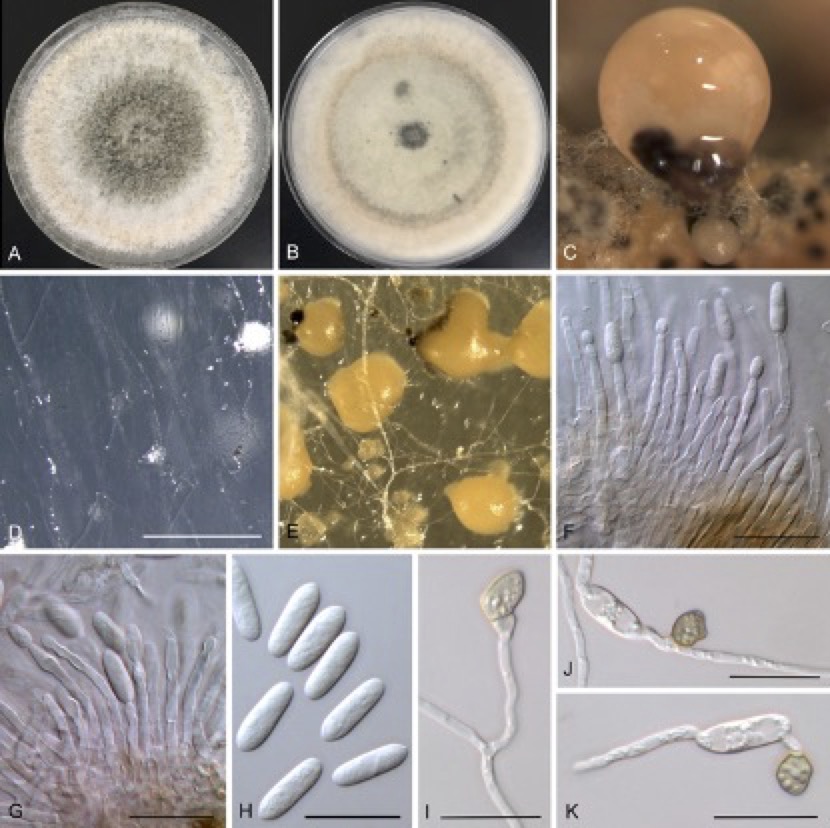

We also measured morphological characteristics including spore length, spore width, spore shape and colony growth rate of Colletotrichum samples. To understand the ability of each species to cause disease – it’s so-called pathogenicity – we tested them on orange fruit leaves and petals, and lemon leaves.

By comparing selected gene sequences of all the Colletotrichum samples, in combination with their morphological characteristics and pathogenicity, we confirmed that Collettorichum gloeosporioides was the pathogen most frequently found on diseased citrus branches, leaves and fruit.

However, as the most frequently identified fungus may not be the most aggressive in causing disease, the next step is to test the virulence of Colletotrichum species among different citrus species on both the trees and fruit.

Understanding the risk that each of these Colletotrichum species pose to citrus trees and post-harvest fruits is essential. Especially for the post-harvest fruit trade which will always be impacted by anthracnose infection because blemished fruit is largely unmarketable in Australian supermarkets.

Unfortunately, Australian mandarins have already shown up in supermarkets in Bangkok with symptoms of anthracnose. These fruits may have been cross-infected in Thailand, however, it’s more likely these were infected prior to export, and only showed symptoms of disease as the fruit matured.

Our future research is being undertaken in collaboration with colleagues in Indonesian, Thai and Philippine Universities to identify Colletotrichum species that are pathogens of citrus and that may pose a biosecurity risk to Australian citrus production should exotic pathogens be allowed into Australia.

Protecting our borders from pests

In addition to anthracnose, many exotic pests and diseases found in countries outside of Australia pose a biosecurity threat to the Australian citrus industry.

For example Huanglongbing, which is caused by a bacterium that lives in the vascular system of citrus trees, is devastating the citrus industries in many countries in Asia and the USA. Bacterial canker which in South East Asia is a major disease in oranges, mandarins and limes was recently discovered in citrus in northern Australia but has fortunately now been eradicated from Australia.

Strict quarantine procedures are required to prevent the incursion of diseased fruit and citrus plant cuttings into Australia, or the exporting of endemic diseases to other countries.

By gaining a better understanding of the Colletotrichum species that cause anthracnose, both within Australia and overseas, an efficient control plan such as development of advanced molecular diagnostic tools (qPCR) for detecting small traces of pathogens in plant material, can be applied to mitigate the risk of disease and therefore better protect Australis’s citrus industry.

Banner: Getty Images