Public attitudes to immunity passports

As Australia and the world navigates its way to a post-COVID-19 normality, what role should immunity passports play and what does the public think?

Published 15 August 2021

Australia’s national COVID-19 vaccination rate is on track to hit 70 per cent by November, and the Australian Government is set to introduce vaccination passports that allow people to travel, enter businesses and return to regular activities.

But should the Australian Government be following in the footsteps of the EU and consider Immunity Passports that confer similar freedoms to people who have already recovered from COVID-19?

Is that fair? And would such a passport risk people seeking to self-infect with COVID-19 just to gain greater freedoms?

To better understand public attitudes to immunity passports, researchers at the University of Melbourne’s Complex Human Data Hub have led an international team to survey more than 13,000 people between April and May, 2020, across six countries – Australia, Taiwan, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the UK.

Vaccination passports

But first, what are vaccination and immunity passports, and who plans on using them?

Vaccination passports are digital certificates that will be accessible through MyGov, and businesses can request them as proof of your COVID-19 vaccination history.

These Green Cards have already been used in Israel, the EU, and for travel from the US to the UK. But why should we use them here in Australia?

Vaccines lower your risk of infection and the severity of your symptoms, meaning you’re less of a risk to others and are less likely to end up in hospital. So, if you haven’t done so already, go book a vaccination appointment now.

But like most vaccines and immune responses, COVID-19 vaccinations become less effective over time.

Additionally, in rare ‘breakthrough’ cases, the vaccinated can still be infected, and these people can spread the virus.

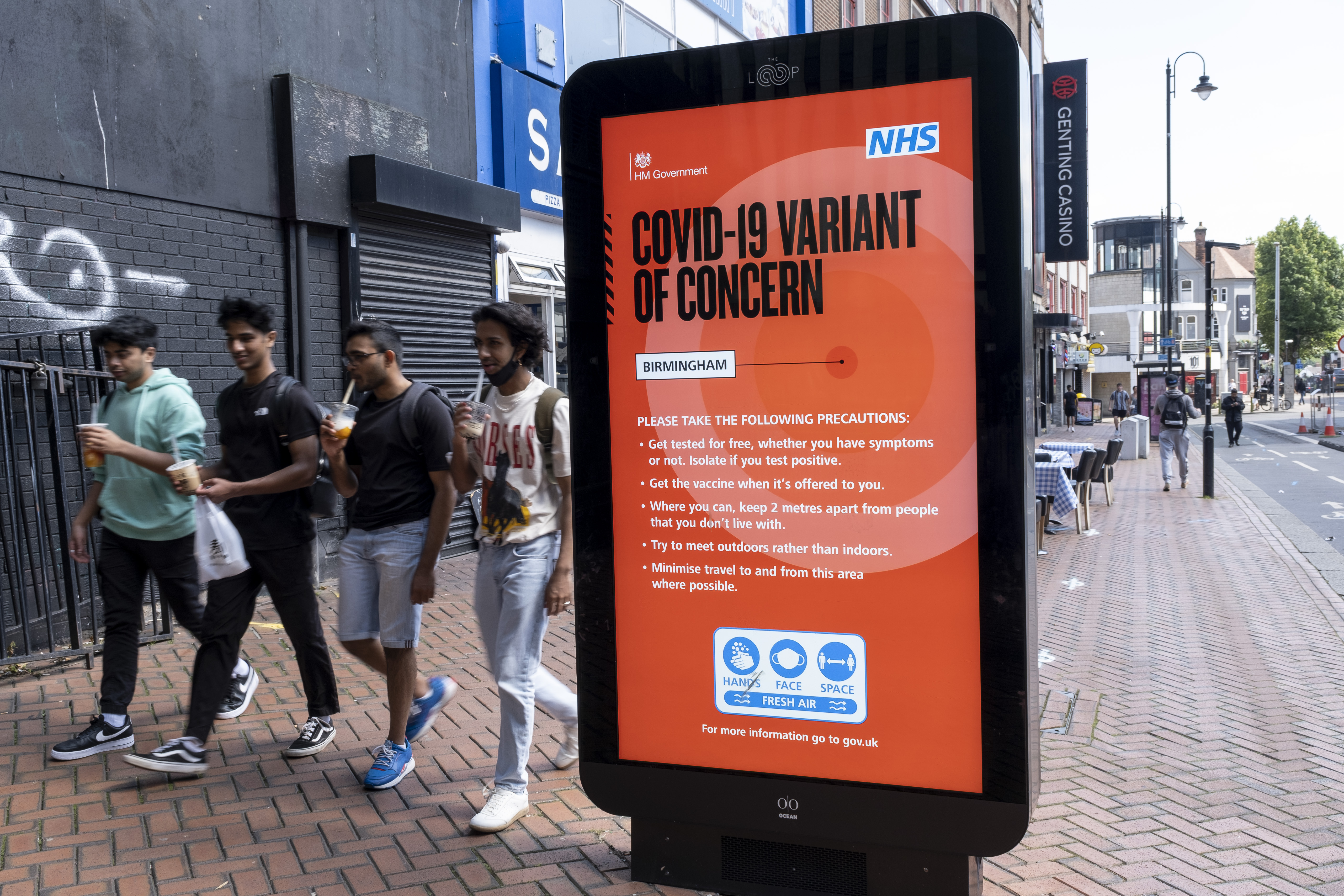

Then there is the ongoing complication of new virus variants.

The Delta variant that is now responsible for most cases in Australia, has doubled the transmission rates of COVID-19. Future variants may prove more infectious, or even resistant to current vaccines, meaning more time and money will be needed to make new vaccine technologies.

Health & Medicine

Privacy and health: The lessons of COVID-19

Considering this, Australia may need to consider not only vaccination, but immunity passports.

Immunity passports

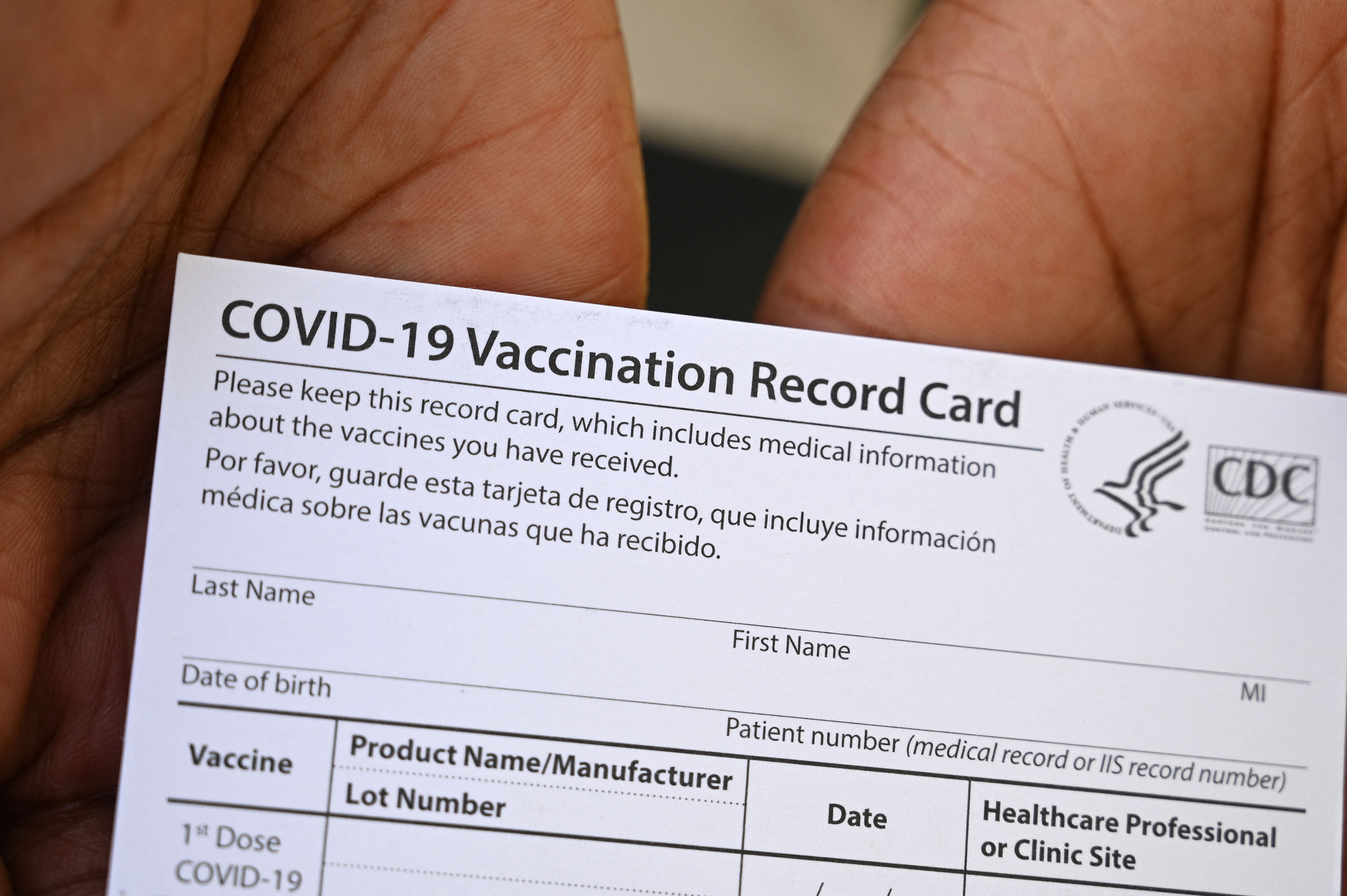

Immunity passports identify previously infected individuals through the antibodies in their immune system that they have developed in response to the SARS-CoV2 virus. Immunity passports document the type and timeline of your SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Passports like these may prove critical in countries with low vaccination rates — Chile and Estonia are already working towards their versions — or in countries where new variants bypass existing vaccine technologies.

Where vaccines are not an option, it may appear obvious that immunity passports could be useful. So, what are the concerns?

Immunity passports, like vaccine passports, risk creating a class divide – those with social freedoms and those without. But they may also encourage individuals to self-infect with COVID-19 as a way to gain immunity and the greater freedoms that go with it.

Health & Medicine

Why social conditions need to guide our COVID-19 policies

What does the data say?

Within each country we surveyed, immunity passport support was moderate-to-low – ranging from 51 per cent in the UK and Germany, 47 per cent in Taiwan, 46 per cent in Australia and Spain, and 22 per cent in Japan.

Interestingly, the prevailing level of COVD-19 infection in these countries didn’t influence the level of support for immunity passports.

Spain was experiencing the most cases at the time of sampling with more than 5,000 cases per day, but showed identical levels of moderate support for immunity passports as Australia where there were fewer than 300 cases per day.

Across the six countries, immunity passports were perceived as moderately fair and desirable, but also moderately harmful and concerning for society. In other words, people want access to these passports, but are worried about their societal consequences.

Predictors of support for immunity passports

Internationally, we found that people were more likely to support immunity passports if they had attitudes aligned with a neoliberal worldview — a belief that the free-market is fair and meets people’s needs.

People also tended to be supportive the more they were concerned about the personal threat and severity of the virus.

Health & Medicine

Giving students time for recovery and learning

However, the strongest influence on support for immunity passports was a belief that they were “fair”, as well as the willingness of people to contract COVID-19 on purpose in order to get a passport.

However very few respondents expressed a willingness to become infected on purpose. The vast majority of people in every country indicated they were “not at all” willing to consider this option.

And this reluctance to “self-inflict” may well have strengthened; this data was collected in early 2020 when the potential long-term effects of COVID-19 or long COVID — chronic fatigue, changes to taste and smell, brain fog, shortness of breath — were unknown.

In terms of caution towards immunity passports, women were more likely to be against them, as were people who saw them as potentially harmful to society.

These results suggest that the more concerned people were for their own welfare the more supportive they were of immunity passports, but concerns over the societal costs of immunity passports aligned with a drop in support.

Health & Medicine

The science of supporting others

Research caveats

The COVID-19 pandemic changes daily.

This data was collected in 2020, when vaccines weren’t readily available and when the highly infectious Delta variant was a thing of the future. In 2021, attitudes may have changed to become more in favour of immunity passports under these new conditions.

We focused our attention on immunity passports because they may be used in vaccinated and unvaccinated countries; but this doesn’t mean our findings cannot extend to vaccination passports.

The same conditions — personal benefits vs society harms — underlie both types of COVID-19 passports and need to be the focus of policymakers selling the public on these new health initiatives.

Two unexplored, yet major concerns about introducing COVID-19 health technologies, is how they will (or won’t) benefit key demographics — older persons, the immunocompromised and minority groups — and who is responsible for their enforcement; governments, or private businesses?

Where to now?

In Australia, there is debate about whether or not the Federal government should mandate requirements for vaccination for high-risk workers or leave it up to businesses.

Health & Medicine

Dealing with feelings about COVID-19

Australian airline Qantas has already indicated a willingness to use a Travel Pass ‘Vaccination’ App to ensure only vaccinated people board international flights. This is similar to the ‘Yellow Pass’ required to prove yellow fever vaccination before entering some countries in Africa.

Governments and corporations around the world are now introducing or considering immunity and vaccination passports as a way to quickly return society and the economy to normal, while encouraging the public to get vaccinated.

However, the introduction of these passports will only work if the public supports their use.

Our research suggests that support for immunity passports is predicted by the personal benefits and risks they confer as well as gender, neoliberal world views and the concern and perceived severity COVID-19 poses to one’s self.

Successfully accounting for these factors in policy decisions regarding immunity passports may be the difference between public acceptance or public backlash when individuals are prompted: “Papers please?”.

This research was conducted by an international team of researchers, including Dr Paul Garrett, Joshua White, Professor Simon Dennis, Associate Professor Andrew Perfors, Associate Professor Daniel Little, and Professor Yoshihisha Kashima, University of Melbourne; Professor Stephan Lewandowsky, University of Bristol; Professor Cheng-Ta Yang, National Cheng Kung University; Dr Yasmina Okan, University of Leeds; Dr Anastasia Kozyreva and Dr Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, Max Planck Institute for Human Development; and Professor Takashi Kusumi, Kyoto University

Banner: The Italian version of the European Union’s Covid-19 Green Pass for travel. Picture: Getty Images