Health & Medicine

How Australia is losing the health fight

Powerful commercial actors have a disproportionate influence on politics, the economy, our climate and our health. So how can we shift the focus from raising profits to improving health?

Published 24 March 2023

Commercial interests shape our world, sometimes with devastating impacts on public health. Pandemic profiteering increased the fortunes of the world’s super-rich by $US 4 trillion as millions lost their jobs and struggled to make ends meet.

In recent years, we have seen some efforts to hold some of the more egregious commercial actors to account.

Purdue Pharma and McKinsey settled for $US8 billion and $US600 million respectively in lawsuits over their role in driving the opioid crisis in the United States, and the US Federal Trade Commission has launched antitrust cases against Big Tech companies, Amazon and Facebook.

Internationally, the G20 summit has proposed a collective tax floor to discourage rampant corporate tax evasion and avoidance.

These efforts are important, but far from sufficient.

It is immensely challenging to address corporate power and influence, not least because the incomes of businesses often rival those of governments. In 2016, 71 of the world’s 100 largest economies were corporations – a rapid rise compared to 51 in 2000.

In short, our global economic system is rigged against the interests of the public.

We are part of a global and intergenerational group of researchers who worked on The Lancet Series on Commercial Determinants of Health (CDoH). The series explores four facets of CDoH: a definition, a conceptual model, commercial actor diversity and solutions.

Addressing the CDoH requires both incremental changes as well as transformative changes to the current capitalist system. Actions are required from many actors, at all levels of the system.

While many commercial actors are part of the problem, there are also opportunities for businesses to adopt alternative business and finance models that have the potential to promote health (including social enterprises, cooperatives and divestment strategies).

Health & Medicine

How Australia is losing the health fight

The series defines CDoH as “the systems, practices and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity.”

This definition recognises that the commercial world is diverse, and the influence of commercial actors on health is often mixed. Commercial actors include transnational corporations, local businesses, sole traders, cooperatives, think tanks and corporate foundations.

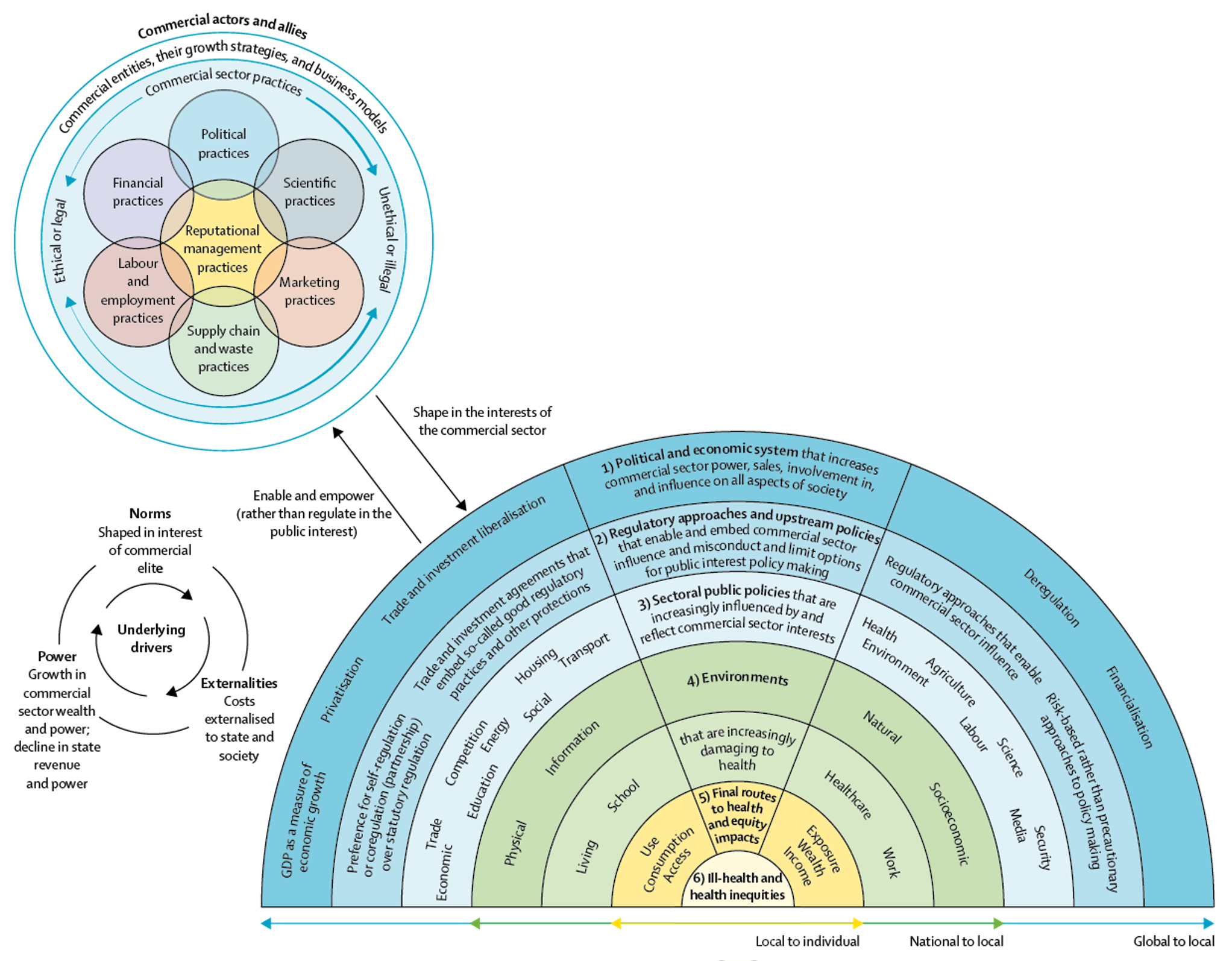

The series developed a model of CDoH to show key aspects of the system and how they interconnect. This can support policymakers, civil society and others to identify levers and entry points to influence the system so that health and equity are prioritised over profits.

Drivers of human health range from close to the individual – for instance, the quality of one’s job, to more distant, like the influence on trade policies shaping the national food environment or tax evasion, which effectively defunds the public sector.

All of these drivers influence health, but they do so in different ways and are often outside the control of individuals and communities.

The seven practices set out in the model are important for understanding the different ways that corporations can influence health. These practices can be health-promoting or health-harming.

Below, we highlight some recent harmful examples from the Australian context.

Business & Economics

Rio Tinto and the anatomy of corporate culpability

1. Political practices, for example, the alcohol industry’s lobbying to block warning labels on their products.

2. Marketing practices, for example, the vaping industry’s use of flavours and colourful imagery to appeal to young people.

3. Scientific practices, for example, the fossil fuel industry is funding research to confuse the evidence on climate change.

4. Financial practices, for example how PwC leaked confidential government information to companies to help them avoid paying their fair share of taxes to the Australian government.

5. Employment practices, for example, a report finding that the gig economy entrenches gender inequality.

6. Supply chain practices, for example, Rio Tinto’s destruction of the sacred First Nations land at Juukan Gorge.

7. Reputational practices – that is, companies routinely engaging in public relations to distract from the above activities.

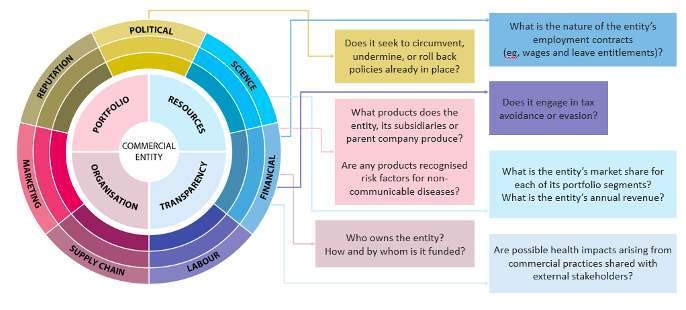

The series also recognises that not all commercial actors are the same.

Much of the private sector overlaps with parts of the public sector (for example, state-owned enterprises) as well as the charitable or ‘third’ sector (for example, corporate foundations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or so-called social enterprises that claim to put people before profits).

Commercial actors also differ in what they make and sell.

While much of the public health literature has focused on harmful products – often tobacco, alcohol, gambling and ultra-processed foods – commercial actors provide a vast range of goods and services, including education, health care, transportation, technology, utilities and renewable energy.

While we may want to decrease the production of tobacco, our concerns about healthcare are more around the quality and equity of access.

Commercial actors vary in size and resources.

While some have revenues rivalling national governments, most enterprises are much smaller. These resources determine the potential scale of health impacts.

Being able to differentiate between commercial actors is important for decision-making about engagement. It’s important for policymakers, investors and others to understand the potential risks and benefits of engagement and to avoid conflicts of interest where possible.

We developed a framework to differentiate between commercial actors and a set of guiding questions to apply the framework. These questions may include how a commercial entity is funded and whether it produces products that are known risk factors for health, like tobacco.

Finally, the series set out a vision for a world in which the interests of the public come before profits.

Business & Economics

Sustainable success for Australian business

This requires actions from many stakeholders, including governments and international organisations, civil society, researchers, health actors as well as the commercial sector.

The Global Health Score is one example of how we might leverage the power of commercial actors to change business practices.

The GHS aims to systematically evaluate the health impacts of businesses to inform financial markets (including ASX, S&P 500) and guide investment decisions.

In writing this series, we and our co-authors seek to create the groundwork for future research and advocacy on CDoH. We look forward to robust conversations and debate, and to working with allies to redress power imbalances and enhance global health.

The Lancet series on the Commercial Determinants of Health was developed by 33 authors, spanning 15 countries and 6 continents, and was supported by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation , the University of Bath, the SPECTRUM Research Consortium, the Australian National University and the University of Melbourne.

Banner: Getty Images