Politics & Society

Biden’s bid to strengthen global democracy

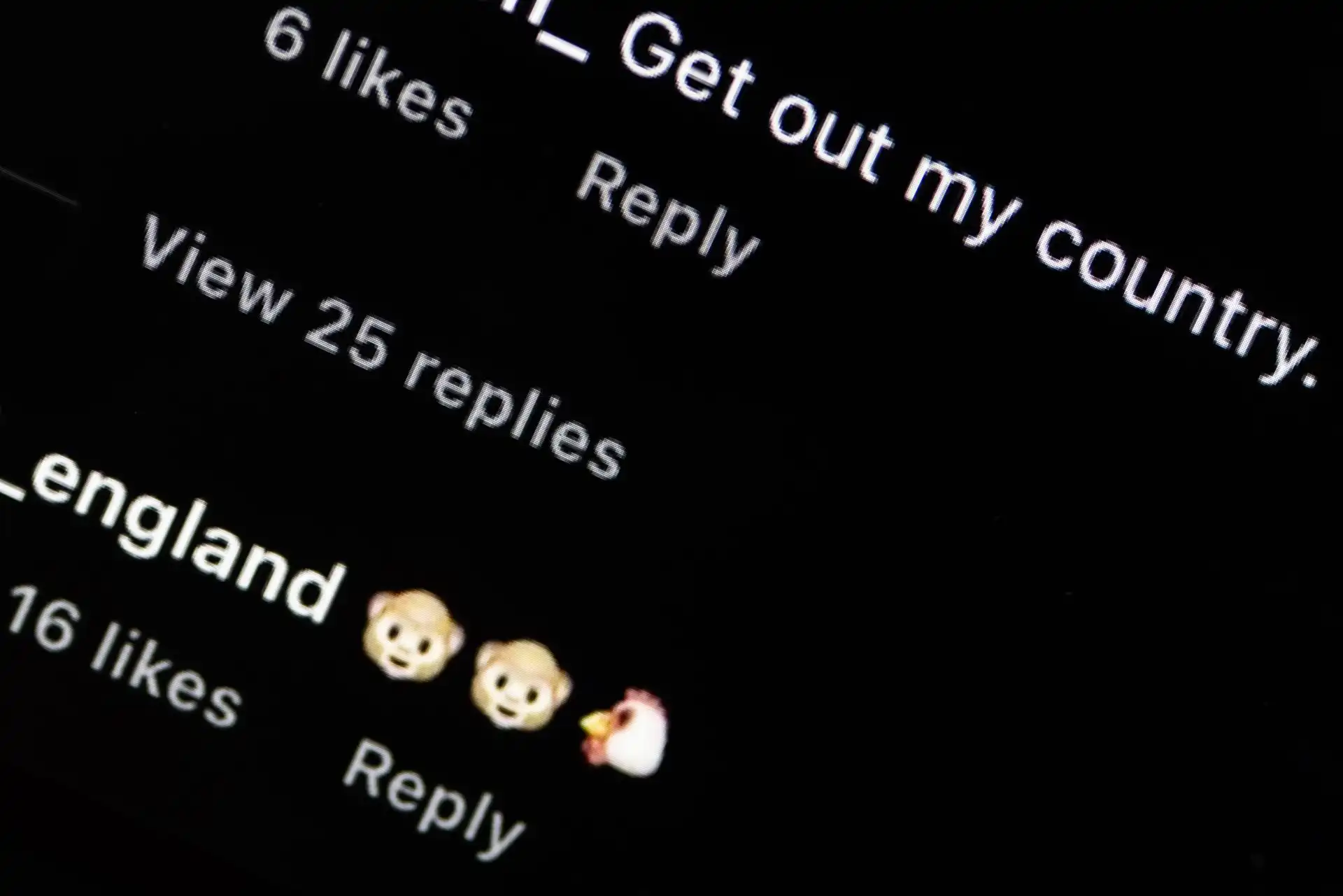

Moral outrage is on the rise – and it’s creating polarisation and division in democracies around the world in a vital election year

Published 7 August 2024

This year – 2024 – is a year that will test the strength of global democracies.

As we reach the halfway point of ‘election year’, many parts of the globe feel as divided as ever.

In the US for example, moral outrage towards the ‘other side’ is rife.

According to 2022 data from the US, 63 per cent of Democrats would label Republicans as ‘immoral’ (up from 35 per cent in 2016). Likewise, 72 per cent of Republicans would label Democrats as ‘immoral’ (up from 47 per cent in 2016).

This isn’t just an American trend.

The rise in moral outrage towards those that we believe are in the wrong can be seen in other parts of the world. From Australia to France and the UK, the battles on university campuses surrounding the Israel-Hamas conflict grew tense and sometimes violent.

Deep moral and political schisms are emerging elsewhere.

Nine in ten South Koreans believe that there are strong conflicts emerging between people who support different parties. And there are grave concerns for rising divisions in places like France, Argentina, South Africa, Sweden, Spain and Colombia.

Who and what can we blame for these trends?

Politics & Society

Biden’s bid to strengthen global democracy

We’ve heard of the typical culprits: dynamics on social media, populist leaders like Donald Trump, and entrenched two party systems – to name a few. There is no doubt each of these factors explain the rise in moral outrage, at least to some degree.

But our work is beginning to show that another factor may be influencing this trend: economic inequality and, in turn, a weakened social fabric.

A society is considered to have high economic inequality when money and assets are spread unequally in a population.

We can see high inequality in action in many countries around the world, from the United States and South Africa to Hong Kong and Turkey.

In the US for example, the richest one per cent of the country have 104 times the income compared to the poorest 20 per cent. Many assume economic inequality just affects how much money people have. But more and more research is now showing that inequality also affects the relationships between citizens in society.

This happens for two reasons.

Sciences & Technology

How to find the truth on Twitter

In unequal societies, people lose a sense of shared identity. How can individuals relate to each other when their lives are so fundamentally different?

But there is also another factor at play: in unequal societies, people stop trusting each other. When trust breaks down, people start to see each other as competitors rather than collaborators.

These factors – the loss of a shared identity and growing distrust – culminate to create a sense that the social fabric of society is crumbling. Put simply, when living in an unequal society, people feel as though they’re on their own and others can’t be trusted to do the right thing.

And this is a problem.

Since the early evolution of humans, we have relied on one another to survive and thrive. A loss of trust and social support is therefore a major threat and can make us feel like we’re no longer in control.

Humans don’t usually cope well with this feeling. To get around this, people tend to behave in ways that make them feel like they are regaining a sense of control. And taking a strong moral stance is one way that makes some people feel in control.

With a team of 45 researchers from around the world, we set out to test this theory.

Our team first took a random sample of six billion Tweets from X, formerly known as Twitter, that were posted in the United States between 2012 and 2020.

Health & Medicine

Why are we so vulnerable to bad information?

We counted the number of morally relevant words (like ‘disgust’, ‘hurt’ and ‘respect’) used in Tweets from each year and town.

We then got the Gini index for each town. This index is a common measure of how unequally income is spread in a population, and the higher the number, the greater the inequality.

Our research found that a higher Gini index clearly predicted a greater use of moral language online. This effect was far stronger for words that were condemning (like ‘hurt’) compared to words that were more virtuous (like ‘help’).

Outside of the United States, we surveyed people from 41 countries around the world asking them how unequal they believed their society was, and then looked at the level of inequality in their country based on data from the World Bank.

Our participants were then given 24 different scenarios and asked them how wrong they were.

These were diverse – spanning lack of respect towards authority (‘You see a student stating that her professor is a fool during an afternoon class’) and examples where someone was hurt (‘You see a teacher hitting a student’s hand with a ruler for falling asleep in class’), to situations where someone was not loyal to their group (‘You see a coach celebrating with the opposing team’s players who just won the game’).

Our study found that depending on how unequal a society actually is in reality, and how unequal people believed their society to be, both predicted a tendency to judge situations as morally wrong.

Why?

Politics & Society

Liberal Democracy: Why we may be losing it

Well, the data suggest that higher inequality is linked to holding stronger beliefs that the social and moral fabric of society is crumbling.

In turn, this predicted the tendency to more harshly judge the actions of others, potentially because it helps participants feel like they’re retaking control of society.

But here’s the Catch-22.

When inequality erodes the social fabric of society, people may try to retake control by policing the behaviour of others. But this well-intentioned moral policing may have the opposite effect.

Rather than bringing us together, an unyielding approach to moral issues can divide us.

Research shows that people who have strong moral attitudes and opinions are also more likely to see their beliefs as objective truths about the world, distance themselves from people who think differently and endorse violence as means to achieve their moral end goal.

So, what does this mean for our modern society? If high economic inequality leads to people holding stronger moral attitudes and opinions, it may actually deepen the divisions among us.

As we navigate this crucial election year, it’s essential to consider the broader factors like economic inequality that can influence polarisation.

Only by addressing these underlying issues will we be able tackle the divisions tearing societies apart and work to safeguard our democracies.