Arts & Culture

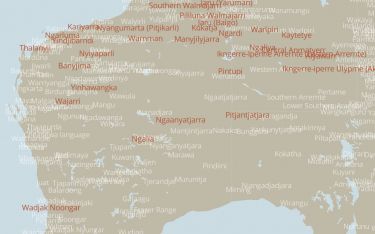

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

There are thousands of agreements in place between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, but Traditional Owners need the right data to inform decision making

Published 11 November 2020

Customary warning: Aboriginal readers are advised that this article contains images and information about deceased persons.

The destruction of the Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto earlier this year highlighted the vulnerability of Indigenous cultural heritage sites in Australia. It was an incident that destroyed evidence of the oldest site of human occupation in Australia, and possibly the world.

Archaeologists had uncovered material that dated human occupation of the area to 46,000 years ago. It also revealed, through DNA testing, that the present-day Traditional Owners are descendants of these ancient people – vindicating the belief that Aboriginal people have the longest, continuous culture in the world in any one place.

Perhaps, just as shocking, the site’s destruction was not unlawful. But it’s also not unusual.

More recently, in the Djadjiling (Mount Robinson, Western Australia), mining company BHP received State government approval to destroy between 40 and 86 significant sites of the Banjima people. This approval came only three days after the catastrophic events at Juukan Gorge.

The global outrage at the destruction of the Juukan Gorge sites snapped the resource industry out of its business-as-usual approach to destroying Aboriginal cultural heritage.

Arts & Culture

50 words in Australian Indigenous languages

BHP imposed a temporary moratorium on the destruction of the sites for which it has received Western Australian government approval under its 50-year old Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act presently under review.

The evidence presented to the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia in its inquiry into the destruction of the sites at Juukan Gorge underscores the need for greater statutory protection of our country’s cultural heritage.

But it also demonstrates the need for fair and transparent agreement making between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians.

There are thousands of agreements in place between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, covering wide-ranging issues including land use, mining exploration and the provision of health services.

These agreements sometimes – but certainly not always – occur under the Native Title Act 1993, and they generally aim to benefit all parties.

But these agreements don’t always work, particularly where parties have little regard for formal agreement provisions, community standards or the spirit of ‘partnership’ with Traditional Owners.

Health & Medicine

Voice. Treaty. Truth.

Research from the 2000s onwards has identified various principles and features that should underpin best practice in agreement making with Indigenous peoples.

Agreement making processes must reflect that Indigenous Australians are more than ‘stakeholders’ and have a special relationship to Country as Traditional Owners. This includes ensuring appropriate representation in negotiations and transparency, as well as effective mechanisms for compliance and review.

Best practice should include first establishing systematic processes:

for identifying the people and organisations potentially affected by the subject matter of the agreement, and then ensuring that they are properly represented in the agreement making process and in the ongoing implementation of the agreements, and

clearly and transparently identifying all the issues of concern that will be covered by the agreement.

For instance, the recent National Agreement on Closing the Gap sets out processes for representation, consultation and shared decision making. This demonstrates a commitment to improved partnerships between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and people.

Once the relevant groups are identified, it’s essential that resources are invested to ensure that the relevant Indigenous organisations can participate meaningfully in negotiations, and the subsequent implementation of agreements, including acting as a liaison between the parties.

In some cases, this will involve communication with a range of different Indigenous interest groups.

Business & Economics

Rio Tinto and the anatomy of corporate culpability

Alongside a robust, well-structured Indigenous organisational and governance structure, it’s important to establish frameworks for the conduct of negotiations, including a clear approval process.

This should be transparent and comprehensive, while also ensuring full and informed consent.

The terms of an agreement must be clear about the issues it covers, as well as the obligations and rights of the parties. The agreements themselves, to the greatest extent possible, should be publicly available.

In addition, best practice also requires structures for clear and transparent monitoring and reporting on implementation, as well as enforcement mechanisms to ensure that the negotiated benefits actually materialise, whether that’s via penalties or incentives.

The public availability of the terms of the agreement and transparency are critical to the outcomes for Aboriginal Traditional Owners.

Agreements with Indigenous peoples often involve long-term relationships and activities, and this is why it is important that there are mechanisms for the ongoing review of the negotiated outcomes — including the possibility for amendment.

At a more general level, best practice in agreement making with Traditional Owners should also consider broader concerns, not just the immediate area of the agreement.

Environment

The time is now for Indigenous design equity

For instance, agreements could include terms that address barriers to employment, provide opportunities for contracting with and developing businesses owned by Traditional Owners, transfer of assets to Indigenous peoples and, of course, ensure the ongoing protection of cultural heritage and Country.

In order to make sure these principles are complied with, it’s important that the parties maintain high standards of documentation, and that institutional frameworks and resources are made available to support Indigenous groups both in the negotiation process, as well as afterwards in terms of compliance.

A key tool here is data – which can empower Traditional Owners with knowledge of what works, and addresses potential power or resource imbalances. And the Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) website aims to provide this information.

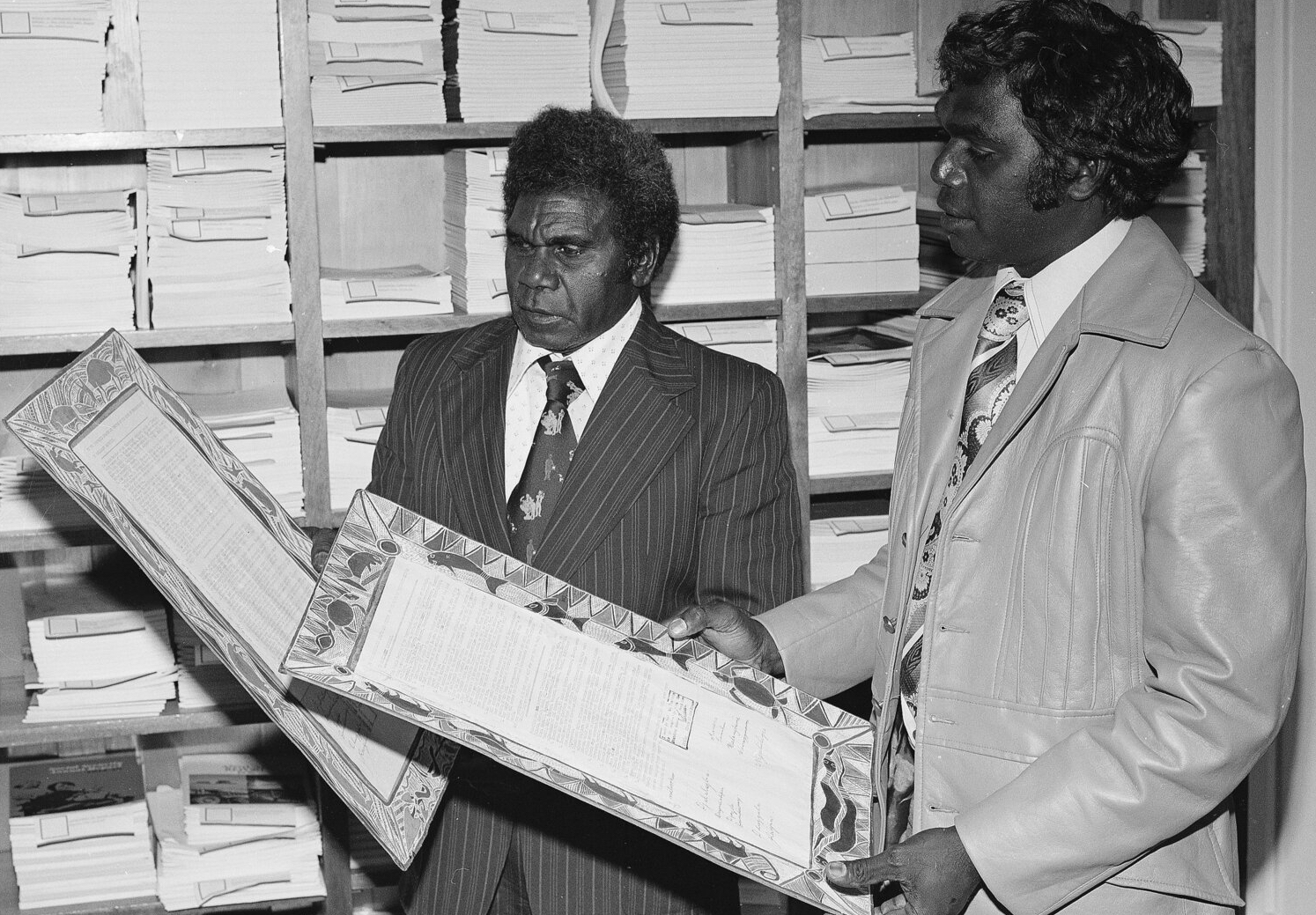

Redeveloped in a partnership between the University of Melbourne and the National Native Title Council (NNTC), the ATNS is the only resource of its kind, capturing the range and variety of agreement making with Indigenous people in Australia and other parts of the world.

Crucially, the free website is continually updated, aiming to provide information to Traditional Owners, community organisations and policy makers.

ATNS aims to support agreement making that effectively protects Indigenous interests and aspirations and puts important knowledge into the hands of people who need it.

ATNS is being re-launched with a live webinar Q&A – Laying the Foundations for Treaty: Agreements, Treaties & Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) new website launch. The online event is at 6pm on Thursday 12th November. Tickets are free but registration is essential. Register here. The Q&A will be recorded and will be available on www.atns.net.au.

Banner: The Juukan Gorge rock shelters in Western Australia/AAP/Supplied by PKKP and PKKP Aboriginal Corporation