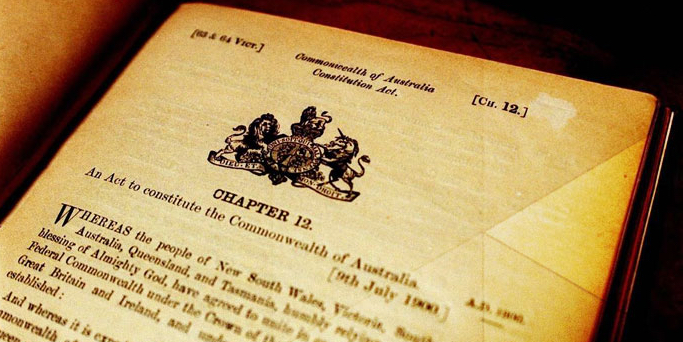

Politics & Society

Australia’s referendum drought

As Section 44(i) of the Constitution continues to claim the scalps of Australian politicians who have dual citizenship - is the law still relevant in modern, multicultural Australia?

Published 21 August 2017

Section 44(i) of the Australian constitution continues to wreak political havoc, affecting minor and major parties all the way up to the Deputy Prime Minister.

It’s a constitutional crisis that shows no signs of abating, so is it time to look at changing the Constitution to reflect Australia’s modern multiculturalism?

We put the question to four of the University of Melbourne’s top constitutional law experts – Professor Adrienne Stone, Director of the Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies; Laureate Professor Cheryl Saunders; Professor Micheal Crommelin and Dr William Partlett – all from the Melbourne Law School.

Section 44 is directed to eligibility for election to the Parliament. It sets out a list of five disqualifications for being a member of the Commonwealth Parliament.

The part of Section 44 that is the primary issue at the moment is Section 44(i), which deals with the question of allegiance and includes a disqualification for those who are dual citizens.

Section 44(i) says: Any person who is under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or a citizen of a foreign power shall be incapable of being chosen or of sitting as a senator or a member of the House of Representatives.

Politics & Society

Australia’s referendum drought

In 1992 in Sykes v Cleary, the High Court made two important statements about 44(i).

First, it said that whether an individual is a citizen of a foreign power is determined by the domestic law of the foreign nation; and second, that Australian citizens holding foreign citizenship will not be disqualified from election to parliament if they have taken ‘reasonable steps’ to renounce their foreign citizenship.

Furthermore, in a second important case in 1999 (Sue v Hill), the High Court expanded the practical effect of Section 44(i), by adopting an interpretation of the words “foreign power” to cover the UK and other countries in the Commonwealth.

A sequence of events has meant that there are now many more people holding citizenship of a ‘foreign power’ than would have been envisaged at the time of the Constitution’s framing.

In 1948-1949, by agreement, Australia developed its own citizenship laws, introducing the idea that Australians were ‘citizens’ rather than subjects of the Queen. Furthermore, the High Court’s ruling in Sue v Hill in 1999 made it clear that countries that have Queen Elizabeth II as head of state nevertheless are ‘foreign powers’ within the meaning of the Constitution, broadening the scope of Section 44(i) to that extent.

Migration has brought many people to Australia who by birth or descent have another citizenship.

Finally, the law has changed, in both Australia and other countries, so that dual citizenship is now much more common. In the past, it was usual that persons taking on the citizenship of a new country automatically lost their prior citizenship. Now the trend has reversed, with many countries, allowing people to hold multiple citizenships.

The result of all these changes is that there are now many, many more dual citizens in Australia and, because foreign citizenship is determined by the laws of other countries, many are not aware of their foreign citizenship.

Parliament has referred five politicians to the High Court but this number likely rise to at least seven, with Senators Fiona Nash and Nick Xenophon recently declaring their foreign citizenship.

Politics & Society

Q&A: Recognising Australia’s first peoples ... properly

Two questions will be put to the High Court. Firstly, the Court will consider whether the referred parliamentarians are in fact citizens of a foreign power according to s 44(i). Secondly, the High Court will also determine on what grounds a person can be disqualified for having dual citizenship.

It is possible the High Court may be able to finesse its interpretation in a way that limits the operation of Section 44(i). For instance, it may consider whether a person’s lack of knowledge or consent provides an exception to disqualification. However, given the clear wording and the Court’s previous decisions, its power to revise the law is somewhat limited.

If Members of the House of Representatives or Senators are disqualified on the grounds that they were citizens of a foreign power at the time of their nomination for the election, then their election is void and there is a vacancy for their seat.

If a Senator is disqualified, a recount of the State’s Senate vote will take place, and the seat will go to the next candidate on the Party’s ticket.

If a member of the House of Representatives (such as Barnaby Joyce) is found to be disqualified, a by-election will be held. A disqualified member could be a candidate in that by-election, provided he or she has renounced foreign citizenship.

If any MP is disqualified who also was a Minister, questions may arise about the validity of ministerial decisions made by that person.

Finally, if it turns out that the Senators who have resigned (Senators Scott Ludlum and Larissa Waters) were properly elected, then they will have resigned mistakenly. In that case, their seats will be the subject of a casual vacancy and the Greens Party can ensure the appointment of new Senators or reappoint Ludlum and Waters.

Recent events show a clear need to amend the section. The general underlying thrust of the provision – the requirement that a person has a primary allegiance to Australia – is still relevant to determining who is eligible to sit in Parliament. However, it is becoming clear that as a practical matter, the section is creating significant problems for the Parliament, due to our multicultural history and the complex nature of dual citizenship under modern law.

The result is that the section has application well beyond its rationale.

Politics & Society

Mapping Australia’s multicultural future

The notion that persons have an allegiance to another country because of their descent or the happenstance of their birth, even when they had no knowledge of possessing such citizenship, is clearly implausible.

It is also inconsistent with the principle that parliament ought to be representative of the people it governs. With nearly half of Australians being born overseas or having a parent who was born overseas, the strict requirements in Section 44(i) seem out of touch with modern Australia.

Yes. Section 44 can be amended using the referendum procedure specified in Section 128 of the Constitution. Although it can be somewhat difficult to amend the Constitution, in this case the need for change is so clear that it should not be a controversial task if a sensible proposal can be devised.

Such a proposal would need to have criteria that make it relatively easy for candidates to ascertain that they meet the requirements of eligibility without too much complex fact finding.

Banner image: BTN