Environment

Building resilience in remote communities

The Global South’s urban poor are often violently displaced and excluded from the processes and places which determine their lives

Published 10 August 2022

In 2021, taking advantage of the instability caused by both the pandemic and monsoon season, the Indian government – using the rhetoric of ‘forest conservation’ – destroyed the Khori Gaon settlement on the Delhi border.

For its residents, already among the most vulnerable in the city, any recompense was stonewalled by cadastral tyranny and bureaucratic indifference, as the settlement straddles two municipalities.

In India’s ‘world cities’, the urban poor are often violently displaced and excluded from the processes which determine their lives.

PhD candidate at the Melbourne School of Design and activist Ishita Chatterjee is a key figure in the group championing rights to representation, land, and amenities.

She has worked to make the residents’ plight known by harnessing social media. The group uses Twitter and a blog – with articles co-written with the residents to document their struggle – and helps the residents run a YouTube channel. In her words, “archiving is a form of activism,” and the group’s efforts ensure that the residents’ stories won’t be misrepresented or forgotten.

Environment

Building resilience in remote communities

This is an example of the disenfranchisement, marginalisation, and oppression of subalternity – or ‘inferior rank’ – and minority in the Global South.

And until these ‘minority’ views become core to the discourse and profession, calls for equity will remain hollow.

But there are other stories of activism – this time in the settlement of Shivaji Nagar in India’s largest city, Mumbai.

The government includes Shivaji Nagar’s central zone in its sites-and-services scheme, which provides support, but it is quick to dismiss the residences on the settlement’s edges as politically off-the-map and, so, ineligible.

Ishita Chatterjee and her team consult with the non-governmental agency Apnalaya, which trains young people in the settlement to collect their own data as one way of confronting the state’s obsolete data.

This strategy not only negotiates the fluctuations of informal settlements, but it also, with its methodology emerging from within, recognises local customs and sensitivities, revealing an authentic picture of a “lived reality.”

The invisibility of subalterns and minorities and the need to subvert it is captured in one resident’s observation: “In the sites-and-services, the postman can reach a house, whereas in the periphery … they can never reach a house [because] we are not on the map. We have to be on the map.”

Politics & Society

A long way from home

Related research by Dr Kelum Palipane, Lecturer in Architectural Design, explores the cultural, physical, social, and temporal aspects of spaces in multicultural communities.

Armed with this standpoint and a desire to engage in “experiential sameness,” Dr Palipane travelled to Pettah in Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo. Pettah is a commercially and ethnically diverse neighbourhood made up of a dense urban grid packed with merchants, pedestrians, traffic, and vendors.

Dr Palipane’s observations reveal the intricacies of Pettah’s streetscapes and how they act both in concert with and in resistance to the built form.

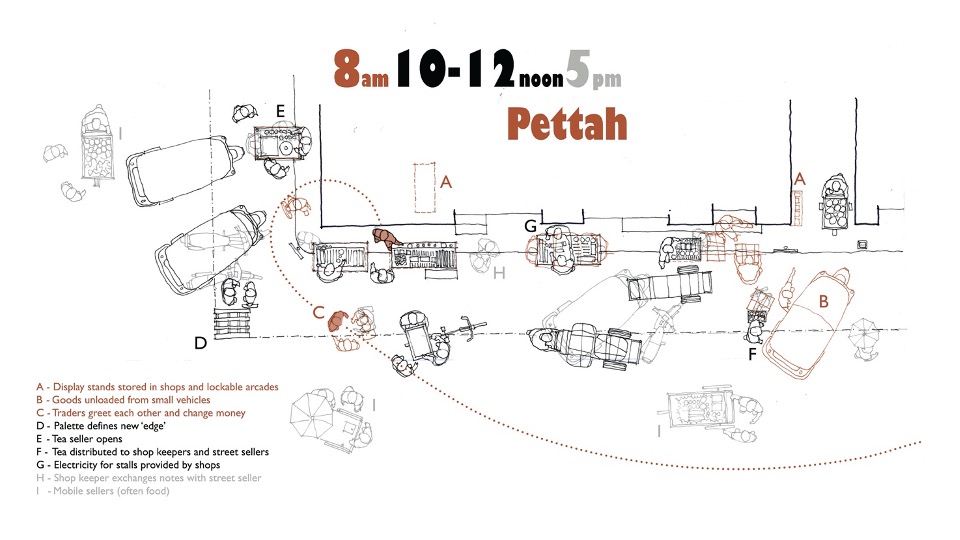

Among other things, Dr Palipane’s work demonstrates that, in Pettah, time significantly influences spaces through distinctly localised phenomena – like how vendors adapt to their customers’ shifts, which corresponds to the “fluctuating urban rhythms” of the working day’s beginning and end (see figure below).

Culture, too, plays a meaningful role. It undergirds the reciprocity between business operators who are indoors and those who are outdoors. Those indoors, with a threshold or a hard boundary, create a permeable space for the removal of footwear and burning of incense.

These fine-grained observations also highlight inequities in the built environment and informality’s capacity to navigate these constraints.

As Dr Palipane notes: “Those who do not possess social capital, who inhabit a tentative and conditional citizenship, deploy socio-spatial markers associated with informality, to gain access to socio-economic and civic domains.”

Politics & Society

History repeating: Losing citizenship in India

Professor Anoma Pieris at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning also draws more directly on personal experience.

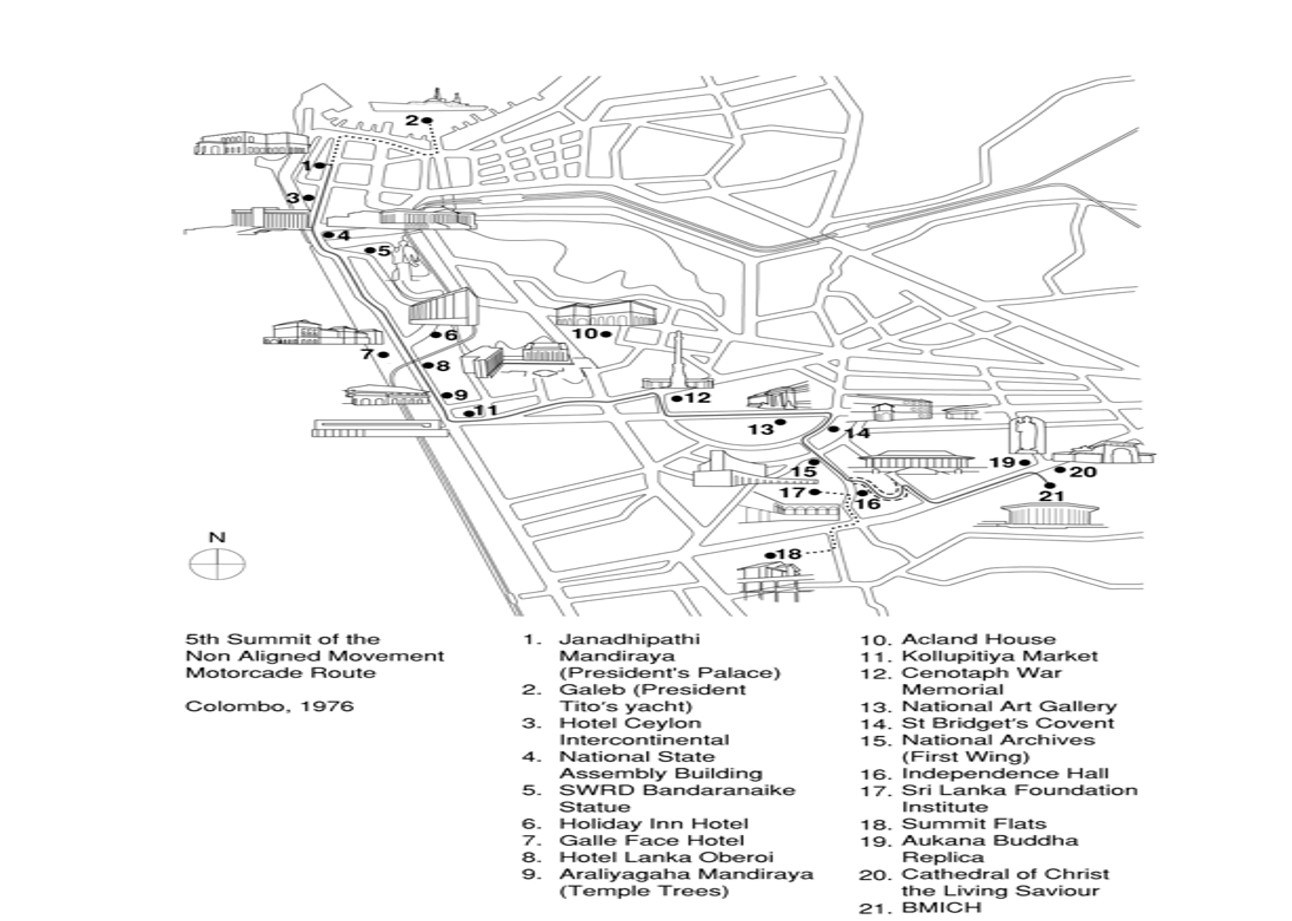

Professor Pieris presents a uniquely autobiographical reading of the 5th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) held in Colombo in 1976.

The summit was a critical moment in South-South diplomacy and she ultimately probes how it unfolded in three-dimensional space amid the economic, political, and racial precariousness of 1970s Sri Lanka.

This exploration is bookended by, on the one hand, Professor Pieris and her family as a collective “subaltern witness” to the summit and, on the other hand, her well-established scholarship of the region’s architectural and urban histories.

The alliance of NAM, formed in 1961 by developing countries seeking to circumvent the antagonism between the Cold War powers, was an opportunity “for expressing nation-state ambitions globally and through the built form.”

More frankly, the built projects which support the summits are instruments of “transnational political leverage”, and evictions and other harsh interventions aid this objective behind the scenes.

In Sri Lanka particularly, the crises plaguing the country at the time must be reckoned as part of the true context of the summit’s glittering backdrop.

The summit asserted Sri Lanka’s prevailing dogmatic identity.

Health & Medicine

No room for saviours in global health

This is seen through the summit logo’s ring of lotus petals (the Buddhist emblem of peace), the renaming of a major arterial road to Bauddhaloka (a Buddhist epithet), and the monumental replica Aukana Buddha sculpture erected opposite the summit venue.

At the same time, contemporary international connections – within and outside of NAM – were reinforced.

The statue of former prime minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was a gift from the USSR, while the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall was designed by the Chinese architect Dai Nianci. And an American presence lurked behind the Holiday Inn, Hotel Ceylon Intercontinental, and Hotel Lanka Oberoi – where the delegates stayed.

Professor Pieris argues that the impacts of structures like these extend beyond the event itself: “summit architectures were trailblazers, programmatic innovations prefiguring developmental processes that marketisation would accelerate.”

Then there was the spectacle of the summit’s motorcade. Professor Pieris recalls: “I stood at a point somewhere midway along this route, along with excited family members, vicariously enjoying our internationalisation through NAM.”

This memory is a poignant one, for, by early the next decade, the same streets would be commandeered by the army and Sri Lanka’s civil war would envelop the built environment – and its subaltern witnesses – into the sphere of its trauma.

This research was presented as part of the Melbourne School of Design’s 2022 Research Seminar Series on Southern Built Environments. You can register for the next seminar in the series, which focuses on the impact of COVID-19 on research in the Global South, on 10 August 2022, both online and in person.

Banner: Two women on a pile of rubble after the demolition of the Khori Gaon Settlement/Picture by Vishakha Chaman with permission of the Khori Gaon website and Team Saathi