Health & Medicine

Parents: 24/7 CEOs of our kids’ lives

Better family-friendly policies in this year’s Budget could help deliver individual, economic and social rewards for everyone

Published 29 March 2019

Men and women both benefit from striking a balance between their work and home life – especially once children come into the picture.

But, at the moment, government policies don’t support parents to share the load and, in fact, often create disincentives for the primary carer to return to work.

There needs to be significant changes made to paid parental leave and the family tax benefit in order to help parents find the balance between a rewarding home life and reaching their career goals.

And these rewards should be felt by men, women, children, businesses and the economy.

Currently, there is no consistency across paid parental leave entitlements in Australia.

Health & Medicine

Parents: 24/7 CEOs of our kids’ lives

The government provides 18 weeks of paid parental leave at the minimum wage to the primary carer and two weeks to their partner. Employers may or may not have leave schemes on top of that.

Paid parental leave should be changed to a real work entitlement that replaces a portion of the primary carer’s regular salary. It should be funded by government and employers through social insurance contributions and provide a universal entitlement of six months of paid leave to every primary carer, as well as extended partner leave.

But there’s a balance to be struck.

When paid leave entitlements are too long, women are likely to find their return to work difficult. If leave is too short, women may not be ready to return to work when their leave runs out and decide to quit their job instead.

This makes returning to work at a later, more realistic point, difficult. Looking at the experience of other countries, the ‘sweet spot’ seems to be around six to twelve months.

Paid parental leave should also make it possible for each parent to have some time as the primary care giver. It benefits both parents – men spend more time with their children and women remain connected to the workforce.

But it’s generally mothers who step into the primary carer role after giving birth and remain in that role for the duration of parental leave.

Health & Medicine

Why helping at home is good for kids

It’s very important that women keep in touch with the workforce when they have children. We know that employment breaks contribute to the gender pay gap and negatively affect savings for retirement.

Women spend a lot of time, energy and money on acquiring valuable skills, but often lose these skills when they’re out of work for a prolonged period.

As a result they may find it difficult to progress in their careers during the child-rearing years and beyond. This comes at a large personal and social cost.

Some countries reserve a portion of parental leave especially for fathers who can “use it or lose it”. For example, five weeks of leave are earmarked specifically for fathers in the Canadian province Quebec, two months in Sweden and Germany, and three months in Iceland. These reforms tend to result in more men spending time caring for their newborn.

This can have knock-on benefits for men and their family relationships. Research from Iceland finds that marriages are five percentage points less likely to break down if the father can assume the role of primary caregiver for a few weeks after a child is born.

In Germany, children (especially the daughters) of fathers who have a portion of parental leave earmarked for them, are more likely to grow up with both parents.

A father’s leave entitlements can also help families in their day-to-day life. In Canada, when the father is entitled to his share of parental leave, families share housework more equitably when the children are eight years old.

Arts & Culture

Crowded house as kids fail to launch

Research from the University of Melbourne shows that both parents get more sleep in more gender-equal societies, where career and family responsibilities are evenly spread. And some studies show that children with more involved dads have better cognitive and social outcomes.

Having two income earners in the family acts as safeguard against immediate financial shock.

In a one-earner family, everything depends on that one person not falling sick or becoming unemployed. Where both parents are earning, they are more financially protected individually and as a family.

For society, this also means that families with two earners are less likely to rely on income support at some point in the future.

But this is not adequately reflected in the tax and transfer system, specifically in how the Family Tax Benefit is set up: the amount of support a family gets is not only based on how much you earn but also on who earned it.

While not always the case, there are a lot of circumstances in which families with both parents working are very seriously penalised compared to one-earner families on the same income.

This is fundamentally unfair and sets all the wrong incentives. Family Tax Benefit Part A and Part B should be harmonised into one payment that financially encourages two-earner families.

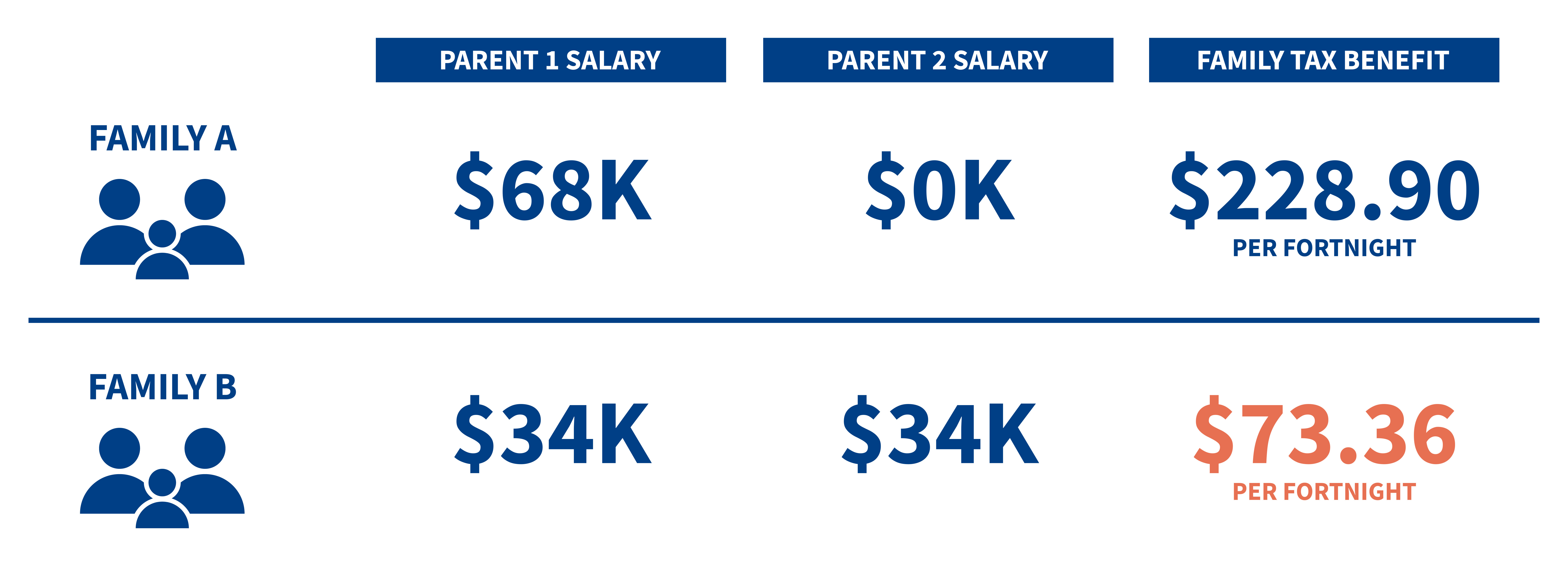

Take, for example, two families, both have two parents and one three-year-old child. In the first family, one parent earns A$68,000 and the other parent earns nothing. The family receives A$228.90 per fortnight. In the second family, each parent earns A$34,000.

They have the same total income, but it was earned by two partners. They receive only A$73.36.

While the payment structure is complex, and it doesn’t always work this way, it is clear that in its current state Family Tax Benefit could be forcing many primary carers to remain out of work.

A fair tax and transfer system and sufficient, well-designed parental leave program would go a long way to allowing men and women to find satisfaction and fulfilment in their families, as well as in their working lives.

Banner: Getty Images