Skyscrapers: How tall is too tall?

As buildings get taller as quickly as technology advances, we asked an expert – how high is too high?

Published 25 November 2015

As global populations spread outwards and lift technology rapidly advances, skyscraper design is becoming ever more futuristic. So we asked Giorgio Marfella, lecturer in Construction Management and Architecture at the Melbourne School of Design – what’s the limit when you’re building in the sky?

Marfella says technological advances combined with logics of economic development are the main reasons high-rise habitats are now luxurious and elite, where once it was frowned upon to sleep or work in the upper levels of a building.

In houses and offices in the past, the first floor was the prime real estate because you didn’t need to use the stairs. But since the introduction of lifts in the late 1800s, it’s now possible to enjoy expansive views of the city, with no dust, less noise, and a speedy trip from the ground floor to the top.

Visionary architects once saw a future where the high-rise was a mark of prestige, and lifts have been the key technology to advance the development of record-breaking building heights.

Marfella says: “In 1956 Frank Lloyd Wright designed the concept of the ‘Illinois’, a one mile high skyscraper for Chicago on the basis of a futuristic – but never realised - atomic powered lift system.

“The practical implications of a mile high tower were such that the Illinois was ridiculed by some American developers at the time.

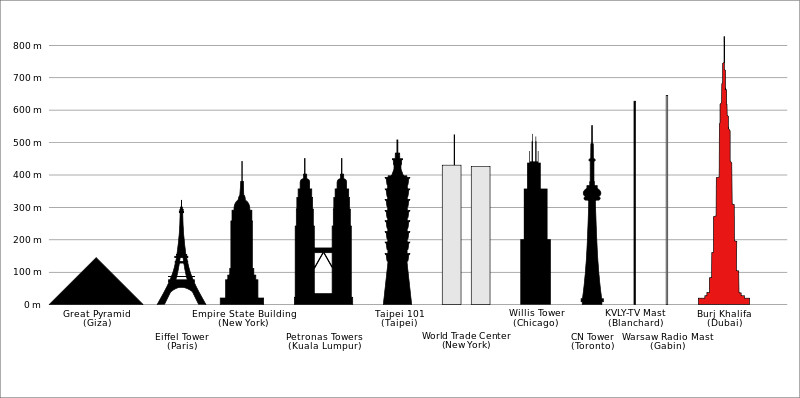

The proposed Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia will be the tallest tower on the planet when it opens in 2019, soaring over a kilometre in height, with “double decker” elevators which will be able to stop at two floors at once. It was previously known as “Mile High Tower”.

Marfella says The Kingdom Tower is reminiscent of Wright’s vision.

“It is one kilometre high, and not one mile, but still, who could have seen that? There is no limit to tall buildings, provided that the technologies of the time allow building at those heights in safety and provided that there is a mutual interest to do so from a private developer and a planning authority’s point of view.

Record breaking tall buildings happen because technology, economy and urban political interests converge at one time into a single project.

Australia has been at the forefront of concrete skyscraper design since the 1970s, and later on with what would have been the world’s tallest building once proposed for Melbourne’s Docklands.

The Grollo Tower, a proposed Melbourne skyscraper that would have soared to 550m if it had been built, was conceived in the mid-1990s by a trio of Melburnians: Grocon (the builder-developer) Denton Corker Marshall (the architect) and Bonacci (the structural engineer). Like Wright’s Illinois, the Grollo Tower, which at the time would have been the tallest in the world, remained an unbuilt vision.

“That was an occasion where the project was stopped by urban politics rather than by technological limitations,’’ says Marfella.

“But in fact the technological approach of this supertall, mixed-use tapered concrete tower was quite realistic, and when the project stopped it had already advanced well beyond a simple architectural vision. In a way this Melbourne project was a precursor of super tall concrete skyscrapers of this century like the Burji Khalifa in Dubai.”

Technology has and will always be rapidly advancing, particularly when it comes to lifts, and progress is this field continues today.

We are now approaching an age where lifts may soon be able to travel faster using a technology borrowed from super-fast rails.

“This new method of vertical transportation, (conceived by Thyssen and known as ‘Multi’) which is about to enter the market, is based on a ropeless lift car which works on the magnetic levitation principle. This new generation of lifts will not only travel faster and serve buildings more efficiently, it will also allow lift cars to travel ‘sideways’ or on a slope.”

While technology is the main concern with tall buildings, there are other issues, particular in relation to the urban constraints of the city in which it is built.

In Melbourne, Australia 108, a high-rise complex due to be finished by 2018 in Southbank, has had to be shortened. The building was originally designed to rise 108 floors and 388 metres (hence the name) but was lowered after it was revealed the building violated federal air-safety regulations for Essendon airport. The developers have now lopped 60 metres off the height, and it will now stand at 319 metres.

Marfella says interruption to flight paths in Australia is a common constraint. But issues of structural and economic efficiency generally and historically have been more important.

“In tall building design circles there is a formula known as the ‘premium for height’. The premium indicates a cost component that grows exponentially in relation to the height of the structure. This cost extra is due to the structural material required to resist lateral loads like winds and earthquakes.”

But strict economic rationales can be usurped by developer ego. The top of the tallest towers in the world is actually often not habitable or directly profitable, apart from ancillary rental opportunities such as space for telecommunication equipment.

Marfella says the biggest issue with super-tall buildings is the same across the world, regardless of views of rivers or flight paths. And contrary to popular belief, it’s not gravity.

“In addition, the topmost part of these structures is often subject to sway that can be extreme, to the point of causing unacceptable levels of motion-sickness to any potential occupier.

“The tallest buildings in the world today are made in concrete rather than steel, to mitigate this issue of sway. Concrete is a heavier material than steel, and the weight of the structure helps to stabilise against wind.’’

While Marfella isn’t necessarily for or against jaw-dropping skyscrapers, he does concede ego shouldn’t come into the height factor, but simply, good design.

There is something primordial about a building that soars in the sky that either attracts fascination or contempt.

“But height for itself should not be the issue at stake. Good design in tall buildings is about balancing the socio-economic potential with the building technologies available at the time. These aspects are not easy to manage, because they require a bolder, more restrained and at the same time broader way of thinking in architectural design.”

Banner image: Southbank’s Australia 108, set to be complete in 2018. Image: FloodSlicer