Business & Economics

How Australians are faring

The number of self-employed entrepreneurs doing well enough to hire staff is shrinking and it’s bigger firms that are behind Australia’s strong employment

Published 31 July 2018

The Australian Government is, to quote from its own marketing material, “committed to helping small business thrive”.

And all evidence suggests they are genuine in this commitment; after all, they have an entire public service department devoted to “jobs and small business”.

The idea here is that boosting small business will boost jobs.

But the evidence from the annual Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey suggests small business may not be the engine of employment it is often claimed to be.

Employment in Australia is at record levels – almost 74 per cent of the working-age population is in paid employment, the highest it has ever been – but HILDA Survey data suggest that the number of people operating small businesses that are doing well enough to hire workers is falling.

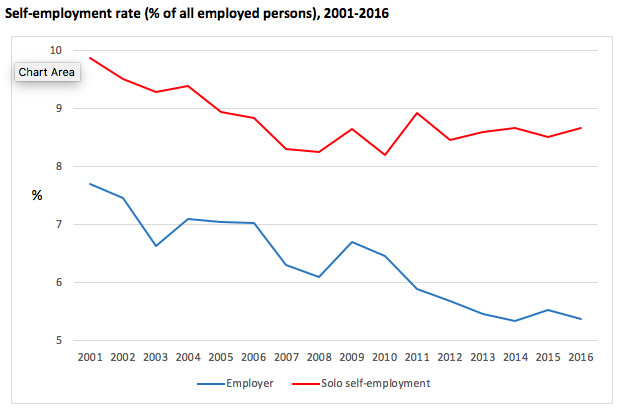

Central to every small business is a self-employed entrepreneur, but growth in self-employment in this country has long been relatively weak and remains so. As a result, self-employment as a share of total employment has been in long-term decline.

Business & Economics

How Australians are faring

HILDA Survey data indicate that in late 2016 self-employed workers represented around 14 per cent of all employed workers, compared with about 17.5 per cent when the survey first started in 2001.

This downward trend has been most marked among those self-employed persons that actually employ other workers, to the extent where their numbers are down in absolute terms. The level of employment among non-employers – or what are sometimes known as the “solo self-employed” – has changed very little since about 2008.

This coincidence of stagnation in employer numbers with a period of record high employment rates strongly suggests that, contrary to what some think, self-employment hasn’t been a significant driver of employment growth. Instead, employment growth has been overwhelmingly concentrated among long established, larger businesses.

This shouldn’t really be all that surprising – a large business, by definition, has succeeded, and so, on average, a large business is likely to continue to be more successful in generating jobs than a new-start up, many of which will not survive more than a few years.

This has always been true, but it doesn’t explain why the share of employers in total employment is in decline.

One answer may lie in factors such as globalisation and technological change, which have worked in favour of very large firms. But this cannot be the entire story given employer numbers are actually shrinking.

This suggests that Government efforts to create an environment in which small business can grow and prosper is failing.

Business & Economics

Is rent-for-life becoming the new norm for families?

Self-employed entrepreneurs are much more reluctant to hire workers today than in the past, which presumably reflects perceptions that the business environment confronting small businesses operators is increasingly hostile to hiring workers.

Another reason why self-employment is not generating more jobs is that relatively few of the solo self-employed will ever take the decision to hire someone. HILDA Survey data show that just 13 per cent of self-employed business operators will have employees three years later.

By contrast, around 25 per cent will no longer be in self-employment.

In short, entry into self-employment is more likely to be associated with failure than success, when success is judged by the likelihood of hiring employees in the future, and failure by the likelihood of ceasing business operation entirely.

Less obvious is the extent to which these so-called failures are a function of the inherent risks associated with starting up and operating new businesses, or because many workers enter self-employment because of the lack of availability of other options.

Self-employment numbers should also be affected by new forms of unregulated contract-based employment associated with the emergence of new digital platforms.

These new ‘gig’ workers are independent workers who move from one job, or gig, to the next, utilising technology created and provided by an intermediary business to connect with purchasers of their services. Often cited examples are Uber drivers and food delivery couriers employed through the likes of Deliveroo, Foodora and Uber Eats.

These workers would typically be classified as self-employed, since they aren’t directly employed by the digital platform.

Business & Economics

Who is doing what on the homefront?

Moreover, we would generally expect such workers to work alone – the prospects of such workers being able to grow a business and employ others would seem remote given their dependency on the intermediary for access to end users.

We’d expect then that growth in the gig economy would be reflected in growth in the number of solo self-employed. But as we have seen, while the rate of solo self-employment hasn’t declined in recent years, there hasn’t been an obvious increase of any magnitude.

If the gig economy is growing as rapidly as commonly believed, then either it involves the substitution of one type of self-employed worker for another (as might be happening in the taxi industry) or it is largely consigned to second jobs, since the HILDA data is based on activity in the main job.

The policy message from HILDA then is that to underpin employment we don’t necessarily need more people starting up businesses; what we need are more small businesses successfully becoming bigger businesses.

Banner Image: Getty Images