Sciences & Technology

Explaining Melbourne’s crazy but predictable weather

In the time it takes 24 horses to run 3.2 kilometres, Melbourne’s weather can change from hot northerly winds to freezing southerly gales. Here’s why

Published 1 November 2024

Melbourne Cup Day means different things to different people.

For some, it’s an exciting day of fashion and competition. For others, it’s a distressing reason for a public holiday.

Many people observe Cup Day as the start of their tomato planting season, while others mark it in their calendar as the day to dust off the Christmas decorations.

Regardless of how you spend the first Tuesday in November, one thing we can all agree on is that the weather this time of year is bonkers.

The big question is, why?

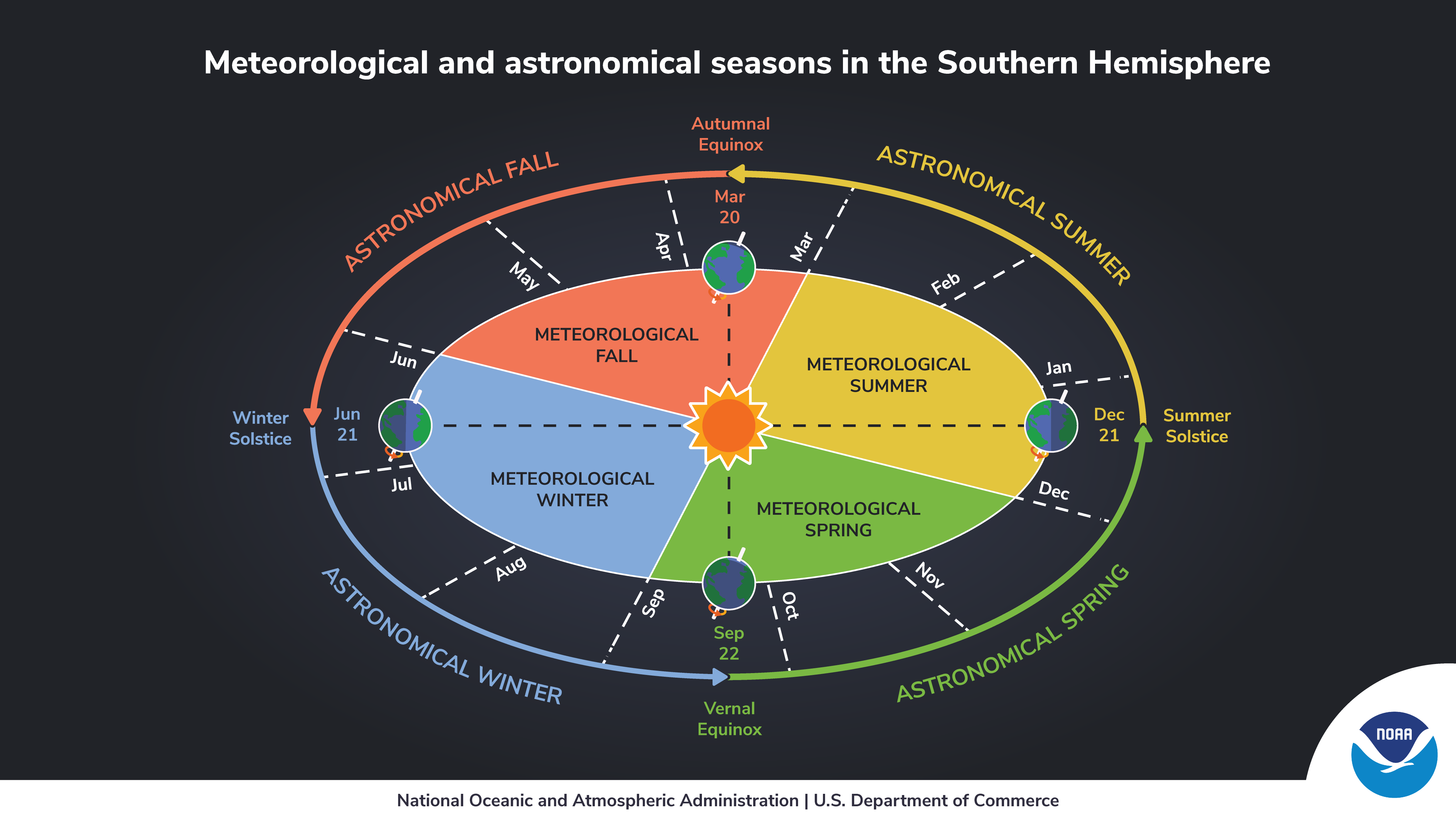

During winter, the Southern Hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun.

The Sun appears lower in our sky, the days are shorter and the Sun’s rays hit us at more of an angle than the Northern Hemisphere, meaning the same amount of energy (or heat) covers a wider area.

Sciences & Technology

Explaining Melbourne’s crazy but predictable weather

As we move towards summer, the Southern Hemisphere becomes tilted towards the Sun and the balance of energy across the planet starts to shift.

In the atmosphere, this rebalance of energy is done through weather systems. The highs and lows you see on a weather map have a crucial job to play in moving heat and moisture around.

And in the transitional seasons of autumn and spring, there is a lot of energy to move.

All of this means that during the Spring Carnival, our atmosphere is busy.

The belt of high pressure centred over southern Australia during winter weakens and moves further south, allowing more tropical weather systems across the country.

At the same time, cold fronts are sweeping up from the Antarctic region trying to shift cold air. These fronts interact with tropical air masses, which can deliver impressive rain and storms.

In fact, October and November are our wettest months, and the months when Melbourne has the most days of rain above 10 millimetres. Spring also sees an increase in wind and thunderstorms compared to the colder months.

In Australia, our weather and climate are also influenced by large-scale atmosphere and ocean patterns like the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

ENSO has its greatest influence on our rainfall in spring, and if we are in a La Niña event, this can often ‘load the dice’ for wetter weather.

Finally, Melbourne’s location also means it’s at the mercy of opposing air sources. We have a dry continent to the north of us and a wet ocean to the south.

By spring, the land has warmed up a lot, but the ocean is still cold.

A shift in wind direction can therefore bring a change from hot northerly winds to freezing southerly gales in the time it takes 24 horses to run 3.2 kilometres.

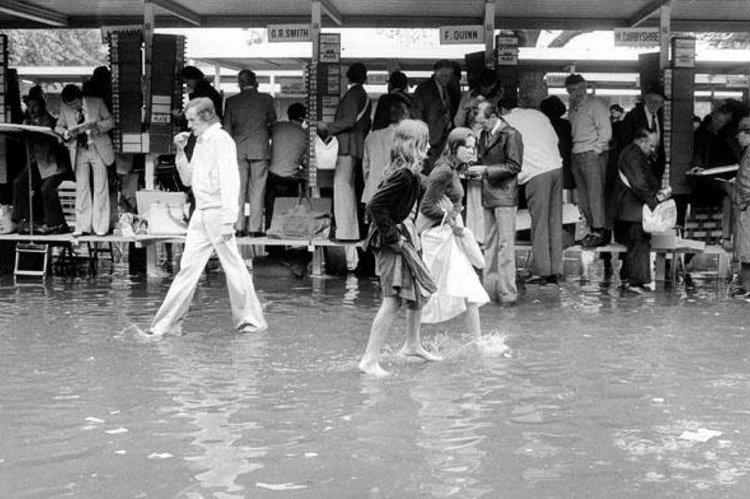

Since 1906 (when the Flemington Racecourse began recording rainfall) the first Tuesday in November has received rain more than 40 per cent of the time, with over a quarter of Melbourne Cup days receiving at least 10 millimetres.

The wettest Cup Day on record occurred in 1976 when a storm “unleashed all its fury” less than an hour before the race.

Temperatures are also highly variable during the Spring Carnival. Cup Day in 1913 was the coldest on record, with attendees shivering through a maximum of 11ºC.

For context, this is colder than the average overnight temperature in November and is actually the coldest November day ever recorded in Melbourne.

But there have also been Cup Days above 30ºC, including the 1928 event, where by 11 am, a “biting wind” had eased and the weather became “delightful”, guaranteeing attendees “ideal conditions for the greatest race in Australasia”.

Sciences & Technology

Nature restoration no substitute for cutting fossil fuels

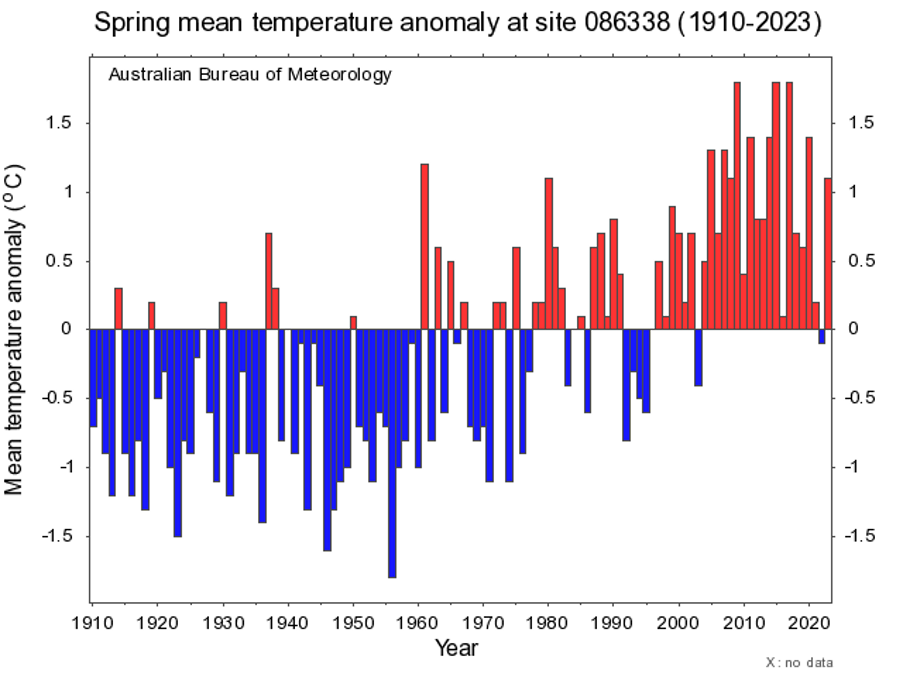

There is no trend in the weather on Cup Day itself, precisely because the swings in weather make it hard to see a long-term signal. But if we zoom out, we can see a clear increase in Melbourne’s spring temperatures.

We are also seeing an increase in heatwaves and an increase in the heaviest of our extreme rainfall events.

Recent studies have also identified an increase in ‘weather whiplash’ events in some parts of the world, where the weather swings violently from one extreme to another.

We’re currently working to understand weather whiplash in Australia, looking at how our dramatic swings in temperature and rain are changing.

These trends are all part of human-induced climate change. Extra greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels are trapping more energy, heating our planet.

The extra heat also makes more moisture available to fall as rain, keeping our weather systems busier than at any other time in human history.

The best thing we can do to stop Cup Day weather from becoming even more erratic is to take action to limit climate change as much as possible. And just like the day itself, this action will look different for different people.

Transitioning to renewable energy, thinking about climate change when making household decisions, joining community groups, interrogating political party climate policies and giving our money to businesses that prioritise climate action – all of these activities can help.

Business & Economics

People or planet? We must invest in both for a sustainable future

We need all of these activities too, and more, to reduce the impact of future climate change.

As for what’s going to happen in the near future?

Your best bet is the Bureau of Meteorology. Their forecast for Melbourne Cup Day is a safer bet than tipping the favourite for the big race.